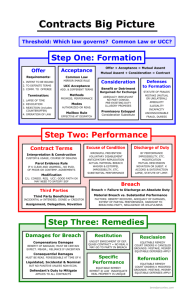

Defenses: Failure of Basic Assumption

advertisement