19th century - Urban growth Early attempts of social housing

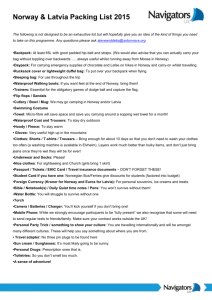

advertisement

19th century - Urban growth Early attempts of social housing 30. august 2013 1850: Industry and urban growth The early industrial revolution The invention of the steam engine (1776) created opportunities for mass transportation: railway and steamships Mechanization and massproduction of products Industrialization, urbanization, speculation, severely bad living conditions 18601900 Urban growth – mobility Slide 2: Europe + USA All over the western world, there were a dramatic urban growth in the 19th century. People moved from the countryside to the cities to work in the industry and to have better access to new commodities. + immigration from Europa to USA. (go through slide) Other cities: Berlin: 173.000 (1800) til 1.6 mill (1900) Amsterdam: Fordoblet antall innbyggere fra 1870-1900 Danmark: Samlet bybefolkning i Danmark nesten fordoblet fra 1850-1880. Fra 220.000 til 420.000. (245.000 i København) Slide 3: Norway Due to improved sanitation and health service the death rate decreased at the beginning of the 19th century. The result was a growth in population that can compare with the situation in the developing countries today. And like all over Europe – people moved to the cities – or to America. The situation for smallholders (husmenn) in the rural areas was very difficult – were not able to support growing families. 1 The conditions in the cities were not much better. There were not enough work in the industry for all the newcomers – and Norway got its first unemployed proletariat. And those who managed to get work gathered in slum areas in the suburbs, close to the factories. The areas lacked water supply and renovation and there were severe cholera outbursts in 1833 (806 dead), 1850 (87) and 1853 (1421dead) (Brantenberg, 1996:105) Slide 4: Housing conditions Demographic density – generally higher in Europe than in USA. The cities were not prepared to receive the newcomers. Several families had to share dwellings. Outbuildings and sheds were used for living. The over population led to: (slide 5) Sanitary conditions injurious to health, unsafe buildings – much due to public neglect and private owners /speculative developers’ greed. High suicide rates, high infant mortality rates (twice as high in American cities as in the rest of the country). High living costs many places (partly due to housing shortage in the cities). Cholera epidemics hit hard. Reactions (slide 6) Housing reform movement arose in several European countries (ref. Tore B). First in England where the problems were greatest, but also in France, Denmark and in Norway. There are several examples of philantrophic projects from the second half of the 19th century where rich industrialists and utopian socialists built housing and ideal socialites (mønstersamfunn). Examples are utopians socialists such as Charles Fourier in France who in the first part of the 19th century developed ideas of the so called Phalanstéres / Phalanx (social palaces). Fourier believed that people would be better off living in communal societies rather than individual, private living. The Phalanstére was 2 meant to be a community of 1,620 based in a single structure. People would own their own dellings, but many activities, including eating and cooking would be communal. His utopia was never realised, but in 1859 the industrialist Godin started constructing what he called Familistére in Guise, based on many of the same ideas. The whole complex consists of three blocks with a courtyard covered by a glass roof. The first block: 1859-60 the third 1877-79. All together 1200 residents. Owned and run as a cooperative until 1968. After that sold to private owners. Historic monument since 1991 – restoration started in 2000. Today both a museum and private housing. In Copenhagen there are two well known examples: Brumleby built by the medical association in 1853-57 after a cholera epidemic in 1853 and Kartoffelrækkerne built by a building association set up by the labor union in 1873-89. For the first time, housing for workers and lower social classes became a commission for well recognized architects such as Bindesbøll and Bøttger Slides: Brumleby + Kartoffelrekkerne Norway (slide 16) Already early in the 19th century, Henrik Wergeland (poet / author and public educationalist ‘folkeopplyser’) tried to wake up the public to improve the housing conditions for the under privileged. Eilert Sundt (regarded as the first social scientist in Norway) – did around 1850 extensive sociological investigations of the urban working class areas as well as the rural poor. He documented the situation of the severe conditions in Kristiania: 3 Families had in average 1,25 room at their disposal – 4,2 persons per room (1858). In the early years of industrialisation, the factory owners built housing for their own workers – mainly to secure enough supply of workers – but also for more idealistic / philantrophic reasons. The philanthropists focused on health and safety: Daylight, ventilation, fire safety. In Norway, the philanthropic societies (all together approx. 20) built 2500 dwellings in total until 1899. Led to some public interventions, internationally in terms of new legislation. However not until the end of the century. English Public Health Act (1875), London Building Act (1894) concerning access to daylight and fresh air, limitations on height, dimension of halos (lysgårder), deck to ceiling heights, requirements for waste and sanitary installations. USA: New Tenement Act (1901). Requirements for increased open spaces providing more light and air, minimum size of sites 50x100 feet. = 15 x 30m Increased public focus on health and security: Light, ventilation, fire safety. Gradually also on ‘public welfare’ issues such as reduced density (open green? spaces), social services, living space and design. Improved housing qualities aimed to both reduce risk for residents and investors on one hand, and proved as a basis for social reform on the other hand (combination of conservative and progressive ideas). A pioneering project was the Arbeiderboligen (1851): ‘The house for the workingclass’. Regarded as the first Norwegian social housing project. Among the initiators was the chief constable in Christiania Christian Morgenstierne. The cholera epidemic a year earlier led to increased attention given to the housing problem (also similar initiatives in Trondheim and Bergen) 42 flats, 6 of them 2 rooms and kitchen. The rest: 1 room + kitchen 4 250 residents in 1851, 5-6 pers per flat (30 m2). Less density than what was normal for the working class. Separate ‘service’ –section in the back yard: 12 privies (utedo) + a larger building with laundry, bathroom, room for drying and taking care of the laundry (rullebod). Improved standard both when it came to living space and hygiene. Also aiming to improve the cultural level of the workingclass: separate library in the backyard. Photo from the 1920s. Later demolished. Another example: Sagveien 8 Halvor Schou got this built for workers in his textile factory Nedre Vøien Spideri in 1848. 3 floors, four apartments (one room and kitchen) with entrance gallery (svalgang) But when the urbanisation process took off – there where more than enough people in search for work – they did not any longer feel obliged to provide housing. And the standard of these flats were very bad. A critical factor was that they did not provide any extra space for growing some food and keeping some animals. People were worse off then they had been outside the cities. During the second half of the 19th century: Among the workers themselves: Increased dissatisfaction and tension within the working class. Increasing doubts among planners / architects and politicians about the apartment building as a model for social housing. It was regarded as unfortunate to stow people together in small space: conflicts, hostility, illnesses, immorality Slottsarkitekt Linstow: regarded an improvment of the workers housing conditions as necessary in order to create peace and harmony among the classes. Didi not believe that the rental baracks with several floors were suitable as homes for workers with families. Only just for older people without children. As an alternative he proposed a privately owned prefabricated house – which was believed to be more in harmony with Norwegian building traditions. This housing 5 type was never built, but the idea was realized Balkeby, built by the landscape painter Peder Balke – as one of the first garden cities at the end of 1850s (later demolished). Economic boom During the 1870s there was an economic boom in Norway – and a massive construction of new housing – which lasted till the turn of the century (collapse in 1899). Speculative rental housing in urban blocks (tenements – ‘gråbeinsgårder’) quarter built with high density and overcrowdedness, lack of daylight, fresh air / ventilation, bad sanitary conditions (clean water, sewage systems). Even if housing issues where put on the political agenda during the second half of the 19th century, housing construction was still regarded as a private responsibility un till the first world war in Norway (1914). Slide 20: Grunerløkka Very high density – not at least because the backyard building no longer were supplementary (service) rooms, but were used for living in full hight. Still, the layout of the flats where improving – they were rather rational (functional) and letting the daylight through (gjennomlyste planer) Doctor and professor Axel Holst carried out a housing survey in 1895. He found that 15000 inhabitants in Kristiania lived in dwellings that were regarded as injurious to health an overcrowded. Slide 21: He formulated some minimum requirements (minimum norms): Adults should have minimum 10 m3 air and children minimum 5 m3. The housing costs should not exceed 20 % the 1913breadwinner’s (forsørgerens) income. 6 Slide 22-23 The need for the public authorities to take responsibility social housing became increasingly recognized towards the turn of the century. First there were given public (municipal) guarantees for private developers – later the municipalities themselves built housing for low income and other vulnerable groups. The largest political parties now had the housing issue at their agenda. Even before the turn of the century there were some scattered examples of public housing projects. Among these were Åkerbergveien 50. This was the first time money was allocated to housing in Oslo. The project took a long time - and only two of them were completed: Åkerbergvn and Dannevigsvn – total of 152 flats. Slide 24 In 1905, more than 10 % of all dwellings in Kristiania were empty – because of the financial collapse – the supply during the construction boom had been greater than the demand. The same situation in Copenhagen. Even though an upward trend started in 1906, this had led to a stagnation in the housing sector. There were only build approx 400 dwellings in Kristiania each year from 1902 – 1914. Housing had become bad business. The result was that the housing situation became worse – in particular during the first world war. The housing shortage increased, as did the prices and the private housing sectors almost ceased to exist. In order to meet this situation, the first Norwegian Housing bank was established in 1903: Norges Arbeiderbruk og boligbank. (workingclass and housing bank?) In 1913 Norwegian association of housing reform was established. Aiming to work for the strengthening / improvement of social housing in Norway. Highly inspired by similar movements in other European countries. Among them the 7 Garden City Movement and Ebenezer Howard in Great Britain (The International Garden Cities and Town Planning Association.) More and more public initiatives were enforced. But it was first after the 2. world war, with the establishment of the Norwegian State Housing Bank that the public role as responsible for subsidising housing construction was formalised. This I will return to in a later lecture. 8