The Weimar Republic 1919-23

advertisement

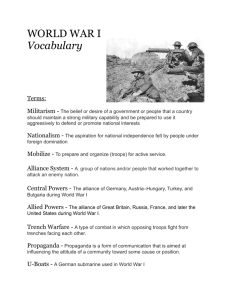

The Weimar Republic 1919-23 The Turbulent Years After the elections of 19 January 1919, the German people found themselves with a democratically elected government for the first time in their history. But this government was not going to have a ‘honeymoon’ period. In March 1919, the Freikorps crushed a general strike, led by the socialist-left in Berlin. The Freikorps, this time in the southern state of Bavaria, also crushed a further left-wing revolt in April, and this led to Bavaria gaining the reputation as a stronghold of right-wing, nationalist sentiment in Germany. But then, on 7 May 1919, the terms of the Peace Treaty (being forged out in the halls of the Palace of Versailles, near Paris) were handed to the German government. Shocked by the severity of their demands, the Germans replied, after three weeks, with over 300 pages of counter-proposals. This did little for the Germans, however, and on 16 June they were given an ultimatum: sign the terms, or the conflict would be renewed. Given that Germany was still at the mercy of the Allied blockade, the government was in no position to seriously consider a renewal of the war. So, on 28 June 1919, after the resignation of Chancellor Scheidemann, as well as half of the German Cabinet (as protest against the Treaty), the Treaty of Versailles was signed in the Hall of Mirrors. This was to burden the fledgling republic with the stigma of having condemned Germany to virtual slavery, only months after its formation. This was a reputation that the republic was always going to find difficult to shake. In July 1919, the Weimar Constitution was enacted. It was extremely democratic, to the point where it was weakness. In its efforts to give a fair representation to the views of all Germans, the Constitution found itself allowing too many parties into the Reichstag; no single party could easily form a majority government, and so governments were always to be awkward coalitions. This instability was to be reflected by numerous elections over the years, resulting in ever-changing coalitions. In March 1920, the Kapp Putsch took place in Berlin. This was essentially a reaction by right-wing military forces to the attempted disbandment of Freikorps groupings (in accordance with the terms of the Treaty of Versailles). When the government called upon the army to suppress the coup, the army refused to do so, and so the government had little choice but to flee Berlin. The failure of the Putsch was only brought about by a general strike by the people of Berlin, led by the left-wing trade unions. After a week of striking, the Kapp Putsch disintegrated, and the government was able to return. However, in the industrial region of the Ruhr, left-wing groups, encouraged by the success of the strike in Berlin, led their own uprising. It was, inevitably, brutally crushed by the Freikorps (who saw it, in part, as an opportunity to avenge the failed Kapp Putsch). So a clear pattern had emerged: there were anti republican forces to both the left and right of the political spectrum, but neither was able to assume power for itself. This was mainly because the people were not prepared to simply submit to the militarism of the right, and they were, it seemed, prepared to give the republic a chance. On the other hand, the Ebert-Gröner Pact (10 November 1918) had seen the military agree to assist the Republic against left-wing insurrections, in return for a promise that the Republic allowed the military to continue to hold a prominent place in society. In April 1921, the Allies demanded the commencement of the reparation payments. One year later, in April 1922, Germany signed the Rappallo Treaty with Russia. This was a treaty of ‘friendship’ (between two international pariahs), and it allowed the Republic some much-needed breathing space from the Communist threat to the east. However, elements of the extreme right-wing saw this treaty as a sell-out to the Communists, and in June 1922, the German Foreign Minister, Walther Rathenau (the man who had signed the Rappallo Treaty) was assassinated in Berlin. Then, in 1923, the Republic faced its hardest year. The French, dissatisfied with Germany’s attempts to meet here reparation payments, invaded the Ruhr in January, in order to force more productivity. At last the political elements within Germany were united – in their hatred of the French! The government adopted policy of ‘Passive Resistance’, and told the German workers to stop working. But while this was done to establish a principle, it had disastrous economic effects on the nation. Having to subsidise the striking workers meant that the government was slowly going bankrupt. This led to rapid inflation, as German money lost its value. The government began printing more and more notes, which in turn escalated the inflationary crisis. Soon the ‘hyperinflation’ was out of control, and the German ‘mark’ quickly became worthless. At last, in November 1923, the new Chancellor, Gustav Stresemann (DVP), ordered the end to Passive Resistance (which, of course, brought about a severe backlash from the extreme right, who felt that he was ‘giving in’ to the French!), and introduced a new currency, the ‘Rentenmark’. For the time being, the economy’s downhill slide had been halted, but the road to recovery was a long one, and was still fraught with danger. Although Stresemann was Chancellor for only a short time (until 23 November 1923), his continuing presence as Foreign Minister in subsequent governments from 1924 until his death in 1929 was to give the Republic a degree of stability that it so desperately needed.