Does brand affect the firm's value?

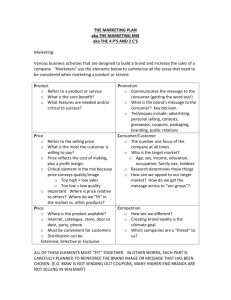

advertisement

Does brand affect the firm’s value? A survey on the top 60 best global brands. Andrea Guerrini – Assistant Professor, Department of Economia Aziendale, University of Verona – Italy Francesco Zaffin – Management Consultant, Vicenza – Italy Andrea Guerrini, PhD is assistant professor at the University of Verona where he teaches Management Control and Intangible Resource Management. He has authored several international publications on Service Management and Controlling. (corresponding author. E-mail: andrea.guerrini@univr.it) Francesco Zaffin is management consultant. He provides brand development and advertising service to SMEs in North East Italy. Does brand affect the firm’s value? A survey on the top 60 best global brands. Abstract Brand is a crucial asset for the success of a firm. There is a huge literature demonstrating how brand affects a firm’s performance and value. By considering the top 60 global brands in Interbrand’s annual ranking, this paper sets out to verify how brand value influences performance and in which sector the relation between these two variables has the greatest impact. Brand values and share prices from 2006 to 2010 were collected and their correlation was tested through a bivariate regression model. The results obtained demonstrate that the influence of brand on a firm’s value is not generalizable and valid for every company; in fact, only two sectors out of the eight monitored were characterized by a strong positively brand impact. These were sectors that supply intangible products, such as business and financial services. Key words: Brand Value; Stock Prices; Services Industry Introduction The current economic system is based mainly on innovation and knowledge, key drivers of competitive advantage (Peteraf, 1993; Mahoney and Pandian, 1992). A competitive advantage must be based on resources that serve to improve the efficiency and the effectiveness of strategies (valuable), that are not widespread among competitors (rare), and that are not imitable or substitutable (in-imitable and non-substitutable) (Barney, 1991). Such features are typical of intangible assets, especially those developed internally (Lev, 2001). The stream of research relating to the Resourced Based View (RBV) paradigm demonstrates that there is a positive relationship between the quality of resources, especially intangibles, and value created (Grant, 1991; Barney, 1991). In summary, the higher the value of resources, the more intense the value creation process within the firm. Intangible assets are defined as identifiable non-monetary assets that cannot be seen, touched or physically measured, and that are controlled and identifiable as a separate asset (i.e. IAS 38). Intangible assets can be divided in two main categories: visible and invisible. The former are those assets that can be ‘viewed’ in the financial statement, such as purchased trademarks, patents, licences, and capitalized Research and Development (R&D) costs. The second category includes certain key assets such as intellectual capital, relationship with stakeholders, and internally developed trademarks that cannot be recorded in the financial statement pursuant to International Financial Reporting Standard n° 38; however, they form a system of resources that is relevant for the achievement of competitive advantage. This research focuses on externally purchased trademarks and their role in the value creation process. The aim of this article is to investigate the impact of brand quality on value created by firm strategy during a certain period of time, as well as to examine the contextual variables that facilitate or inhibit this relation. Specifically, the study focuses on the impact of variations in brand value on share prices. Establishing a link between brand and firm value is important (Yeung & Ramasay, 2008) because, like other investments, brand must produce future cash flows to cover initial expenditure to justify the investment to the financial market; at the same time, this makes it possible to include brand equity in the balance sheet. Existing literature on brand equity, financial performance and shareholder value generally demonstrates a positive relation among these variables. However, there is scarce evidence of the estimation of the way in which a brand can affect firm value in a specific industry sector. This paper seeks to add to the existing and relatively limited evidence in this area by estimating the relationships between brand values and financial performance as well as stock performance in 8 industry sectors. To achieve this research aim, a sample was selected from the top 60 companies listed in Interbrand’s Top 100, operating in 8 different industries. Then, stock market values and brand values were collected from 2006 to 2010 for each company to verify the kind of relationship linking these two variables. A total of 550 observations were collected. This paper is structured as follows. The next section presents a literature review based on the analysis of the role of intangible assets in the process of value creation. Then, a methods section highlights the steps followed during research, the data collected and the statistical tools used. Finally, a results and discussion section presents research evidence and practical implications. Literature review Intangibles have been widely discussed by scholars, various studies being concerned with their nature and the way they affect firm performance. More specifically, the authors who investigated the relationship between intangibles and value created by a firm have observed specific kinds of assets, such as relationships with customers, investments in R&D, brands and patents. In their study of non-financial measures, Ittner and Larcker (1998) demonstrated a strong impact of customer satisfaction on the stock market, with a positive correlation between customer satisfaction and share prices. Customer satisfaction was investigated further by Anderson et al. (2004), who developed a theoretical framework to specify the influence of customer satisfaction on future customer behaviors. The authors demonstrated a positive relation between customer satisfaction and shareholder value; their results also highlight a significant difference across industries and firms. These results make it possible to conclude that certain intangible assets, such as market share and customer satisfaction, positively affect the future financial performance trend, as shown also by Banker et al. (1999). Among research enquiring into the effect of intangible investments on performance, Lev and Sougiannis (1996) focused their study on the relevance of R&D investments, highlighting the importance of such investments for shareholders and investors. The authors demonstrated that high investments in R&D determined long-run stock returns. In this sense, Lev and Zarowin (1998) also investigated the relationship between intangible assets and firm value, finding that investments in R&D were directly linked with firm performance. In summary, these studies presented science and technology investments as predictors of stock performance. This view was adopted also by Deng et al. (1999) who tested the relationship between patent related measures and stock returns, and concluded that patent citations are significantly related to future capital market performance. With reference to technology, Aboody and Lev (1998) examined the relevance for investors of software development costs. The authors analyzed the relationship by linking the latter variable with stock prices and with future earnings, and showed that annually capitalized software development costs are positively associated with stock returns. With science and technology, intellectual capital is also crucial for firms’ longterm success, as Brennan and Connell (2000) demonstrated. More in general, the studies cited above demonstrated that higher investment in intangibles corresponded to growth in stock value (see also Hand and Lev, 2003). Leaving aside the intangibles mentioned above, brand has been recognized as one of the most important assets available to firms; several studies have focused on the relationship between brand and firm performance. Farquhar (1989) developed a study on brand equity management, showing that a successful brand extension leads to the creation of barriers to entry against competitors. This was one of the first studies to evaluate the influence of brand management on competitive performance. Then, following prior studies on intangibles, Aaker and Jacobson (1994) showed that brand building pays off for shareholders. They proved that stock returns are positively associated to changes in ROI and that there is a strong positive relationship between stock returns and brand value. Lane and Jacobson (1995) observed stock market reactions to brand extension announcements, but their findings revealed a nonlinear relationship. Mizik and Jacobson (2008) tried to establish a link between brand attributes and the financial bottom line, arguing that brands provide incremental information in explaining stock returns: they found that stock returns were associated not only with accounting performance measures, but also with perceived brand relevance and strength. Similar results were obtained by Yeung and Ramasamy (2008) who investigated the link between brand strength, financial ratios and stock returns. Rego et al. (2009) focused their research on linking Consumer Based Brand Equity (CBBE) with firm risk, showing that brands with higher levels of average CBBE help to reduce debt-holder risk, firms’ equity risk and, as a consequence, firm’s value. These studies focused on different aspects, yet all found that intangible assets played an important role in creating higher value for companies, and that good management of intangible assets led to better performance, even if the different research outcomes were in some aspects contradictory. Without doubt, brand emerged as one of the most important assets a company can leverage. Table 1 summarizes the literature on brand and value creation. Table 1. Some relevant studies on the link between brand and firm value. Following this approach, our study was designed to investigate a possible correlation between a specific intangible asset, brand, and stock prices; moreover, unlike prior literature, it sought to determine the role played in this relation by the industry sector in which a firm operates. The literature on this second theme is rather scarce. Kim and Kim (2003) found that for fast food, luxury hotel and chain restaurant brand equity had a positive effect on firm value, showing that more than 50 per cent of performance can be due to brand equity. Kim et al. (2003) studied in depth the hotel industry, observing a positive correlation between brand equity and revenue per available room. Baldauf et al. (2003) investigated building tile resellers, and provided supportive evidence that brand equity components, such as brand awareness, perceived quality and brand loyalty, explained respectively 34%, 31% and 17% of firm performance. This article attempts to provide new evidence on the impact of brand on firm value by considering a sample of companies from different industry sectors to investigate more effectively the impact of the type of company activity on this relation. Research questions and method This study focused on the relationship between brand value and the share price of the company holding this specific asset. The research questions were: 1) Does a company with a strong brand receive positive feedback from financial markets and so record higher stock prices? 2) Do different types of company activity affect the intensity of the brand value-share price relation? Considering the principal results of the literature review, our first hypothesis was that a positive correlation exists between variations in brand value and variations in share prices. According to the prior literature, it was possible to hypothesize that growth in intangible value, due to new investments or to an increase in current value, will positively affect stock prices and, consequently, firm value. The second hypothesis was that the intensity of the relation could be affected by other variables, such as industry sector. More specifically, it was hypothesized that companies operating in a more intangible economy, such as firms providing business and financial services or luxury goods, would show a more intense effect of brand value on stock prices. These research hypotheses were tested by collecting financial data for 60 listed companies for five years. We compared the brand values provided by Interbrand’s annual Best Global Brands report from 2006 to 2010, and the historical stock prices publicly available on the web. Interbrand is the world’s largest brand consultancy, with 40 offices in 25 countries. Best Global Brands includes a ranking of the best 100 brands with their specific value. A brand can be valued according to three main criteria (Salinas and Ambler, 2009). The first is oriented toward costs and is based on the historical cost of creation of the brand or of a similar brand. The second looks to the market and estimates brand value by observing the current prices at which this kind of asset can be exchanged. The third method evaluates a brand through the discounted future cash flows that this asset will be able to generate. Interbrand develops its report with a specific method. To include a brand in the ranking, several criteria are considered (www.interbrand.com). 30% of revenues must come from outside the home country and no more than 50% from the same continent: this criteria determines some excellent outsiders not included in the ranking, such as Walmart. A second criteria states that every brand must be present in at least 3 continents and in growing and emerging markets, with publicly available performance data: as a consequence, BBC, Facebook and Mars are not considered. Following selection of the companies, brand earnings are defined by multiplying economic profit by role of brand, the portion of income attributable to brand and derived from research or expert panel assessment. The final brand value is the result of branded earnings actualized by a brand strength discount rate. Of the three methods presented above, the one applied by Interbrand is based on discounted cash flows generated by the brand. Our sample was defined by considering Interbrand’s 2010 Best Global Brands report. The top 60 companies monitored were categorized in 8 industries, as presented in table 2. Table 2. The research sample Most of the sample companies are listed on the New York Stock Exchange, the world’s largest stock exchange by market capitalization; we used the closing share prices on the last trading day for each year considered. For the few companies listed on other stock markets, we used historical exchange rates to convert prices into USD, and then compared these with the other values collected. From the initial sample, we had have to exclude five companies owing to lack of data. First of all, MTV was excluded because it owns a brand but is not listed, so it was not possible to record its share prices. Then, other companies such as RIM and Thomson Reuters were included in the Top 100 Best Global Brand for a shorter period than time horizon. In total 550 observations were analyzed, after collecting brand values and stock prices recorded at the end of each year from 2006 to 2010 for 55 companies. Following collection of data on brand value and share prices, annual share price variations and brand value variations for each company were calculated. Then, the hypothesis was tested using a bivariate regression analysis model that included the abovementioned variations. The model was applied to the entire sample and also to each subsample of companies operating in individual sectors to identify possible differences across industries. Results and discussion This section presents and discusses the key research findings. Table 3 shows variations in brand values and share prices from 2006 to 2010 for each of the 55 companies. Table 3. Sample company data First of all the regression model was applied to the entire sample. The dependent variable, measured by the annual stock price variation was negatively correlated to the independent variable, identified by annual brand value variation (β = - 0.0190). However the p-value was very high (p-Value: 0,75) and consequently this relation was not significant. As a result hypothesis one had to be rejected. This result was clearly due to the great number of variables affecting stock prices aside from brand. As was widely demonstrated by prior studies, stock prices depend also on other financial indicators, such as annual net income and cash flows, financial ratios and specific occurrences (change of governance, entry of a new competitor to the market and so on). Despite this far from exciting result, the hypothesis that brand value affects share price in specific industry sectors was tested. Table 4 presents the mean value of share price and brand value variations for each industry. Table 4. Mean brand values and share price variations for each industry. The data highlights some differences among sectors. More specifically, it seems that brand values and stock prices have similar variations in some industries, such as Business Services, Financial Services and Fast Moving Consumer Goods. This suggests that in these sectors a correlation exists between the variables observed. To investigate this aspect further, the regression model was applied to each industry. Table 5 presents β coefficients and related pValues. Table 5. β coefficient and p-Value. Six industries out of eight were characterized by a strong influence of brand on stock value. It is interesting to observe the nature of this relationship (positive or negative) and its intensity. Four sectors (Automotive, Diversified, FMCG and Luxury) presented a negative relation: hence an increase (decrease) of brand value was related to a decrease (increase) of the stock price. This unexpected relation is attributable to other variables, mentioned at the beginning of this section, that may condition stock prices. Conversely, two services industries, Business Services and Financial Services, were characterized by a positive relation between the two variables. So, an increase (decrease) of brand value determined a certain increase (decrease) of stock prices. These results show that brand can dramatically influence firm value, but only in some specific sectors, especially those offering ‘only’ flows of know-how rather than tangible products to their customers. For the Business Services sector, which includes global leaders in Information & Technology, such as IMB and SAP, and in Consulting and System Integration, as Accenture, results obtained demonstrated that brand values and stock prices varied by the same proportion, with a β coefficient of 0.85. As a matter of fact, these latter companies base their success above all on brand, rather than other resources. The same considerations can be made for the Financial Services sector, even though in this case negative variations were recorded for both variables. In conclusion, while hypothesis 1 was rejected, hypothesis 2 was partially accepted. The hypothesized relation affected the Business Services and the Financial Services sectors, while the Luxury industry showed a negative correlation between brand and firm value. This result, which differs from what was was initially forecasted, could be due to the small number of firms included in the Luxury sector (only three) or to the impact of other variables not observed in this study. Conclusion This study enquired into the effects produced by brand on a firm’s value. It was based on the RBV paradigm, whereby a competitive advantage is created by a stock of resources held by a firm: among these, intangible assets play a key role in the process of value creation, on account of their specific features such as rarity, imperfect imitability and substitution. Prior literature provided evidence of the effect of brand on firm value: the majority of scholars showed that stock prices were influenced by various aspects including the brand value trend. Conversely, this article found no linear correlation between the two variables investigated, if all the 550 observations were considered. In summary, it is not possible to generalize that brand strength influences firm value. Consequently, our first hypothesis was rejected. However, the data confirmed the second hypothesis that a correlation exists between variations in brand value and variations in stock prices characteristic of intangible asset intensive industries, such as Business Services and Financial Services. This implies that companies operating in these two industries earn a greater part of their revenues from brand awareness, perceived quality and loyalty compared to firms from the other sectors monitored. In conclusion, this research shows that not every company needs to pay attention to brand to the same extent. Brand is a critical success factor particularly in industries that do not offer a tangible product, so that customers have to evaluate the quality of supply through brand power. One strength of this study was its cross-sectoral point of view, although it was characterized by two main limitations. The first was that the dataset included only two variables, brand value and share prices variations, while in fact other measures could be monitored to explain the trend of the dependent variable. Secondly, to investigate the intensity of the relation between brand and share price in each sector, more robust results would have been obtained from a larger sample. References Aaker, D. A. (1995) Building strong brands. Brandweek 36(37): 28-34. Aaker, D. A. and Jacobson, R. (1994) Study shows brand-building pays off for stockholders. Advertising Age 65(30): 18. Aboody, D. and Lev, B. (1998) The value relevance of intangibles: the case of software capitalization. Journal of Accounting Research 36(3): 161-191. Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C. and Mazvancheryl, S. K. (2004) Customer satisfaction and shareholder value. The Journal of Marketing 68(4): 172-185. Baldauf , A . , Cravens , K . S . and Binder , G . ( 2003 ) Performance consequences of brand equity management: Evidence from organizations in the value chain. Journal of Product And Brand Management 12(4): 220 – 236. Banker, R. D., Potter, D. and Srinivasan, D. (1999) An empirical investigation of an incentive plan that includes nonfinancial performance measures. The Accounting Review, 75(1): 65-92. Barney, J. (1991) Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management 17(1): 99-120. Brennan, N. and Connell, B. (2000) Intellectual capital: current issues and policy implications. Journal of Intellectual Capital. 1(3): 206-240. Deng, Z., Lev, B. and Narin, F. (1999) Science and Technology as predictors of stock performance. Financial Analyst Journal 55(3): 20-32. Farquhar, P. H. (1989) Managing brand equity. Marketing Research 1(9): 24-33. Grant, R. (1991) The Resource-based Theory of Competitive Advantage: Implication for Strategy Formulation. California Management Review 33(3): 114-135 Hand, J. and Lev, B. (2003) Intangible assets: values, measures, and risks. Oxford University Press, Oxford Ittner, C. D. and Larcker, D. F. (1998) Are nonfinancial measures leading indicators of financial performance? An analysis of customer satisfaction. Journal of Accounting Research 36: 1-46. Kim , H . B . , Woo , G . H . and Jeong , A . A . ( 2003 ) The effect of consumer-based brand equity on firms’ financial performance. Journal of Consumer Marketing 20(4): 335 – 351. Kim , W . G . and Kim , H . B . ( 2004 ) Measuring customer-based restaurant brand equity: Investigating the relationship between brand equity and firms’ performance. Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly 45(2): 115 – 131. Lane, V. and Jacobson, R. (1995) Stock market reactions to brand extension announcements: The effects of brand attitude and familiarity. The Journal of Marketing 59(1): 63-77. Lev, B. (2001) Intangibles: Management, Measurement, and Reporting. Donnelley and Sons, Harrisonburg, Virginia. Lev, B. and Sougiannis, T. (1996) The capitalization, amortization, and value-relevance of R&D. Journal of Accounting and Economics 21(1): 107-138. Lev, B. and Zarowin, P. (1998) The market valuation of R&D expenditures, NYU Stern School of Business, New York. Mahoney, J. T. and Pandian, J. R. (1992) The Resource-Based View Within the Conversation of Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 13(5): 363-380. Mizik, N. and Jacobson, R. (2008) The financial value impact of perceptual brand attributes. Journal of Marketing Research 45(1): 15-32. Peteraf, M. A. (1993) The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3): 179-191. Rego, L. L., Billet, M. T. and Morgan, N. A. (2009) Consumer-Based Brand Equity and Firm Risk. Journal of Marketing, 73(6): 47-60. Yeung, M. and Ramasamy, B (2008) Brand value and firm performance nexus: Further empirical evidence. Journal of Brand Management 15(5): 322-335. Table 1. Some relevant studies on the link between brand and firm value. Authors Published in Focus on Farquhar (1989) Journal of Advertising Research Aaker & Jacobson (1994) Advertising Age Kallapur & Kwan (2004) The Accounting Review Mizik & Jacobson (2008) Journal of Marketing Research Explaining stock return Yeung & Ramasamy (2008) Journal of Brand Management Link between brand value and firm's performance Rego, Billet & Morgan (2009) Journal of Marketing Consumer Based Brand Equity and firm risk relationship Brand equity management Brand building and stockholder relationship The value relevance and reliability of brand assets Method Sample A successful brand extension leads to barriers to entry Theoretical Study n/a EquiTrend database 34 major US corporations Global Vantage's 1998 33 UK firms for financial year since 1985 Y&R BAV database; CRSP database; COMPUSTAT quarterly database; Thomson Financial database The Business Week Top 100 Global Brand Value and a proprietary financial database, Thomson Banker One Database EquiTrend database; COMPUSTAT database; CRSP database Results 275 "monobrand" publicly traded firms 50 US companies over the 2000-2005 period 252 firms over the 2000-2006 period A strong positive association between brand equity and stock return Positive association between market returns and brand asset values Analysis shows that perceived brand relevance and energy provide incremental information to accounting measures in explaining stock returns The study proved a link between the brand equity measure (brand values) and multiple profitability ratios and stock market performance measures Firms that possess brands with strong CBBE are able to significantly reduce their equity risk Table 2. The research sample Industry N° of companies Automotive 8 Business Services 5 Diversified 5 Electronics, Computer&Internet 14 Financial Services 6 FMCG 10 Food & Beverages 4 Luxury 3 Total 55 Table 3. Sample company data 2007 Sector/ firm Automotive Audi BMW Daimler Ford Honda Porsche Toyota Volkswagen Business Services Accenture Cisco Systems IBM Oracle Sap Diversified Adidas Caterpillar General Electric Nike Siemens Elect. Com& Int. Amazon Apple Canon Dell eBay Google HP Intel Corp. Microsoft Nintendo Nokia Panasonic Sony Yahoo Financial Services American Express Citi Goldman Sachs HSBC JPMorgan Morgan Stanley FMCG Avon Colgate Danone Gillette Heinz Johnson&Johnson Kellog's Kimberly L'Oreal Nestlè Food & Beverages Budweiser Coca-Cola McDonald's Pepsi Luxury Gucci Hermes Louis Vuitton stock price variations 23.43% 35.62% -1.48% 41.24% -10.39% -15.77% 59.69% -20.83% 99.34% 7.61% -2.44% -0.47% 12.38% 32.11% -3.54% 30.95% 47.62% 18.31% -0.59% 29.71% 59.68% 43.46% 134.46% 134.78% -18.62% -2.86% 10.38% 51.25% 23.17% 31.51% 19.37% 117.15% 88.14% 1.74% 26.84% -8.93% -15.59% -14.26% -47.07% 7.11% -8.41% -9.75% -21.13% 20.52% 19.64% 19.50% 18.55% 64.04% 3.71% 1.03% 4.66% 2.05% 43.40% 28.65% 20.73% 0.00% 27.43% 34.15% 21.34% 61.15% 41.14% 1.34% 140.96% brand equity variations 6.89% 16.83% 10.17% 8.13% -18.76% 5.57% 10.46% 14.78% 7.94% 7.20% 8.44% 8.94% 1.58% 8.63% 8.42% 7.20% 11.12% 10.46% 5.44% 10.15% -1.16% 10.17% 14.96% 20.89% 6.15% -5.73% 10.38% 44.13% 8.50% -4.22% 3.13% 17.85% 11.83% 3.97% 10.36% 0.18% 10.09% 6.04% 9.25% 10.61% 16.70% 12.03% 5.92% 5.21% 1.25% 6.96% 7.17% 4.27% 5.16% 7.89% 6.44% -5.00% 10.22% 7.75% 1.47% -0.09% -2.50% 6.90% 1.56% 11.12% 7.53% 10.40% 15.42% 2008 stock price variations -39.62% -30.81% -49.07% -59.80% -65.97% -35.44% -96.22% -38.44% 58.82% -24.44% -8.99% -39.82% -22.73% -21.65% -29.02% -42.98% -47.98% -38.44% -56.19% -20.44% -51.86% -48.38% -45.23% -56.24% -31.35% -57.77% -57.94% -55.73% -27.95% -44.74% -45.32% -49.48% -58.81% -39.14% -60.10% -47.55% -56.73% -64.33% -76.29% -60.26% -42.07% -27.64% -69.80% -25.75% -39.21% -12.08% -32.79% -50.36% -19.45% -10.30% -16.81% -23.94% -39.24% -13.32% -2.91% 38.88% -26.85% 4.09% -27.77% -36.26% -46.62% 10.55% -72.70% brand equity variations 5.04% 11.12% 7.80% 8.52% -12.09% 6.01% 4.53% 6.17% 8.23% 9.54% 8.94% 11.56% 3.40% 11.11% 12.70% 4.42% 6.40% 4.53% 2.94% 5.57% 2.66% 8.93% 18.91% 24.51% 2.79% 1.22% 7.18% 43.47% 5.91% 0.99% 0.51% 13.48% 6.67% 3.53% 5.24% -9.41% -6.08% 5.34% -13.94% -3.11% -3.10% -5.77% -15.90% 5.10% 3.16% 6.84% 7.75% 11.14% 1.56% 3.98% 3.95% 0.78% 6.57% 5.23% 2.16% -1.84% 2.06% 5.62% 2.80% 7.02% 7.24% 7.52% 6.30% 2009 stock price variations 53.19% 7.30% 44.55% 39.23% 336.68% 56.80% -18.13% 27.83% -68.76% 37.93% 26.56% 44.65% 54.00% 36.35% 28.07% 21.94% 40.31% 27.58% -7.41% 28.17% 21.06% 50.09% 160.24% 140.18% 33.29% 37.28% 68.55% 99.35% 39.37% 36.73% 54.88% -34.54% -19.39% 15.35% 32.48% 37.54% 48.51% 116.11% -52.98% 95.98% 16.96% 30.46% 84.54% 24.93% 31.09% 19.86% 1.83% 83.39% 13.72% 7.66% 20.69% 20.80% 28.54% 21.79% 2.66% -24.13% 25.27% 0.08% 9.41% -4.36% -73.33% -4.21% 64.47% brand equity variations -7.54% -7.34% -6.98% -6.69% -11.28% -6.69% -5.37% -7.99% -7.99% 0.09% -2.99% 3.40% 2.00% -0.95% -1.00% -2.59% 6.41% -5.37% -10.00% 4.00% -7.99% 0.97% 22.13% 12.31% -4.00% -12.01% -8.02% 24.97% 2.50% -2.00% -4.00% 4.99% -3.00% -1.31% -12.00% -7.01% -24.87% -31.76% -49.17% -10.48% -20.03% -11.35% -26.41% 4.10% -6.59% 1.76% 10.21% 0.67% 9.00% 7.40% 7.39% -5.00% 3.20% 13.00% 3.49% 3.45% 3.10% 3.95% 3.45% -0.87% -0.87% 0.50% -2.23% 2010 stock price brand equity variations variations 34.16% 1.01% 18.26% 9.00% 85.06% 3.00% 36.26% 5.50% 67.90% 2.71% 16.90% 3.95% 27.45% -6.00% -6.30% -16.40% 27.74% 6.29% 9.99% 4.78% 16.84% -2.97% -15.46% 5.40% 12.35% 7.50% 27.72% 8.63% 8.48% 5.37% 34.17% -2.10% 20.44% 1.82% 64.34% -6.00% 21.28% -10.40% 29.29% 4.00% 35.50% 0.10% 7.78% 7.73% 35.52% 23.00% 53.50% 37.00% 22.14% 10.00% -5.64% -13.71% 18.27% 15.01% -3.48% 36.20% -17.72% 11.50% 3.24% 4.50% -8.40% 7.50% 9.46% -2.39% -19.22% -15.40% -1.74% 2.98% 23.86% -4.99% -0.89% -2.99% 5.60% 4.68% 6.05% -6.86% 43.81% -13.33% -0.02% 1.34% -10.04% 10.00% 1.87% 28.94% -8.07% 8.00% 6.33% 4.51% -7.75% 3.15% -2.17% 5.63% 2.57% 6.76% 42.40% 2.00% 15.67% 4.00% -3.97% 8.01% -3.61% 5.88% -1.05% 3.00% -0.48% 3.01% 21.65% 3.62% 14.09% 3.17% 10.80% 3.54% 14.67% 2.50% 23.09% 4.04% 7.81% 2.59% 36.77% 3.17% 5.25% 2.00% 56.96% 4.00% 48.11% 3.50% Table 4. Mean brand values and share price variations for each industry. Mean stocks price Mean brand equity variations variations 17.79% 1.35% 7.77% 5.40% 11.02% 1.73% 13.24% 6.95% -4.55% -4.04% 6.51% 4.73% 8.64% 2.57% 14.33% 5.11% Sector Automotive Business Services Diversified Electronics, Computer&Internet Financial Services FMCG Food & Beverages Luxury Table 5. β coefficient and p-Value. Industry Automotive Business Services Diversified Electronics FMCG Financial Services Food & Beverages Luxury β -0.4123 0.8589 -0.4351 -0.0172 -0.3557 0.3803 -0.1497 -0.7354 p-Value 0.0082* 0.0000* 0.0297* 0.8879 0.0112* 0.0382* 0.5289 0.0018*