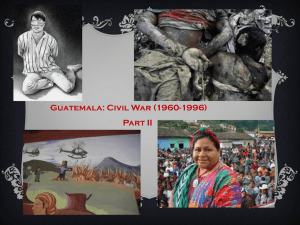

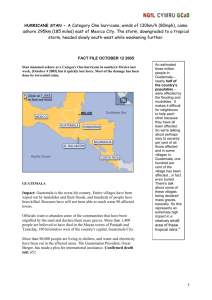

Peace-making and Conflict Transformation in Guatemala

advertisement