Иностранный язык - Учебно

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ

ФЕДЕРАЛЬНОЕ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОЕ БЮДЖЕТНОЕ ОБРАЗОВАТЕЛЬНОЕ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ

ВЫСШЕГО ПРОФЕССИОНАЛЬНОГО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ

«ТЮМЕНСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ»

ФИЛИАЛ ТЮМГУ В Г. ТОБОЛЬСКЕ

Факультет истории, экономики и управления

Кафедра иностранных языков и МП

Рабочая программа учебной дисциплины

«Иностранный язык »

(английский язык)

Направление подготовки

050100.62 Педагогическое образование

Профиль

История, право

Квалификация (степень) выпускника

Бакалавр

Форма обучения заочная

Тобольск 2014

1

2

1.

Цели и задачи освоения дисциплины

Цели

освоения дисциплины (модуля): достижение практического владения английским языком становление иноязычной компетентности; приобретение знаний и навыков иностранного языка, уровень которого позволит использовать приобретенный языковой опыт в профессиональной и научной деятельности.

Задачи:

- активизация навыков восприятия аутентичной иноязычной речи на слух;

- дальнейшее развитие навыков владения диалогической и монологической иноязычной речью;

- совершенствование навыков чтения и понимания (с элементами перевода) иноязычной литературы по специальности;

- усовершенствование навыков письма в пределах изученного языкового материала.

2. Место дисциплины в структуре ООП ВПО

Дисциплина «Иностранный язык в профессиональной коммуникации» включена в вариативную часть профессионального цикла основной образовательной программы бакалавриата.

Дисциплина является самостоятельным модулем.

3. Требования к результатам освоения содержания дисциплины

Процесс изучения дисциплины направлен на формирование элементов следующих компетенций в соответствии с ФГОС ВПО и ООП ВПО по данному направлению подготовки

(специальности): а) общекультурных (ОК):

- владеет способностью осуществлять письменную и устную коммуникацию на государственном языке и осознавать необходимость знания второго языка (ОК-20);

- владеет готовностью к практическому анализу логики различного рода рассуждений, владеет навыками публичной речи, аргументации, ведения дискуссий, полемики (ОК-21).

В результате освоения дисциплины обучающийся должен:

Знать :

- лексический запас магистра должен составить не менее 3000 лексических единиц с учетом вузовского минимума и потенциального словаря, включая термины профилирующей специальности;

- определенные приемы, позволяющие совершать познавательную и коммуникативную деятельность;

- структурные типы простого предложения, грамматические формы и конструкции; порядок слов простого предложения;

- виды письменных и устных высказываний в различных коммуникативных ситуациях;

- разговорные формулы этикета профессионального общения, приемы структурирования научного дискурса.

Владеть:

- подготовленной, а также неподготовленной монологической и диалогической речью в пределах изученного языкового материала и в соответствии с избранной специальностью;

- терминологией по специальности, а также дискурсивными, лексико-фразеологическими, грамматическими и стилистическими трудностями в текстах, относящихся к сфере основной профессиональной деятельности;

3

- правильно оперировать языковыми средствами английского языка в ситуациях устного общения;

- всеми видами чтения (изучающее, ознакомительное, поисковое и просмотровое);

- письмом в пределах изученного материала (250-300 слов).

Уметь:

- понимать аутентичную нормативную монологическую и диалогическую речь носителей иностранного языка;

- работать с оригинальной литературой научного характера, сопоставлять и определять/ выбирать пути и способы научного исследования (изучение статей, монографий, рефератов, трактатов, диссертаций);

- применять полученные знания для преодоления трудностей при переводе с учетом вида перевода, его целей и условий осуществления.

Приобрести опыт деятельности

в решении социально-коммуникативных задач в профессиональной, научной, культурной и бытовой сфер деятельности.

4. Структура и содержание дисциплины

Общая трудоемкость дисциплины составляет 3 зачетных единиц (108 часов), из них 36 часа, выделенных на контактную работу с преподавателем.

.

4.1. Структура дисциплины

Таблица 1

№

Наименование раздела дисциплины

Семестр

7

ЛК

Виды учебной работы

(в академических часах) аудиторные занятия

ПЗ

3

ЛБ

СР

12 1

Стратегии устного и письменного перевода. Методы перевода.

2

Технология предпереводческого анализа.

3

Составление резюме.

4

Научная статья. Аннотирование и реферирование.

5

Моя научная работа.

6

Деловая переписка.

7

Деловое общение по телефону.

8 Международное научное сотрудничество.

7

7

7

8

8

8

8

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

12

14

14

14

14

14

14

4.2. Содержание дисциплины

Таблица 2

№ Наименование раздела дисциплины

Содержание раздела

(дидактические единицы)

4

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Стратегии устного и письменного перевода.

Методы перевода.

Технология предпереводческого анализа.

Составление резюме.

Научная статья.

Аннотирование и реферирование.

Моя научная работа.

Деловая переписка.

Деловое общение по телефону.

Международное научное сотрудничество.

Виды перевода (художественный, научно-технический, общественно-политической).

Методы перевода. Метод сегментации текста - письменный перевод; метод записи - последовательный перевод; метод трансформации исходного текста - синхронный перевод.

Жанры текстов и их учёт при переводе.

Перевод профессионально-ориентированных текстов.

Усложненные структуры (конструкции) в составе предложения.

1) Формальные признаки цепочки определений в составе именной группы (наличие нескольких левых определений между детерминативом существительного и ядром именной группы).

2) Формальные признаки сложного дополнения (

Complex Object).

Лексические, синтаксические, стилистические и грамматические средства, характерные для каждого типа текста: научного; научно-технического; специального.

Формальные признаки логико-смысловых связей между элементами текста (союзы, союзные слова, клишированные фразы, вводные обороты и конструкции, слова-сигналы ретроспективной (местоимения) и перспективной (наречия) связи.

Формальные признаки конструкции "именительный падеж с инфинитивом".

Основные части резюме: 1) личная информация; 2) цель; 3) образование; 4) профессиональный опыт; 5) специальные навыки; 6) рекомендации.

Аннотация. Виды аннотаций.

Аннотирование профессионально-ориентированных текстов.

Времена группы Perfect. Безличные предложения.

Работа с текстами профессиональной направленности.

Особенности научного стиля.

Новые лексические единицы и речевые образцы, необходимые для составления обоснования по теме диссертации.

Правила составления деловых писем, мотивированного письма.

Виды сложных предложений.

Этикет общения по телефону, речевые образцы и лексические единицы по данной теме.

Научная конференция. Умение речевого общения: прием зарубежных специалистов, обмен информацией профессионального характера.

Новые лексические единицы и речевые образцы по теме.

5. Образовательные технологии

Таблица 3

№ заня- тия

№ раздела

Тема занятия Виды образовательных технологий

Кол-во часов

5

1

2

3-4

5

6

7-8

9

10-11

12

13

1

1

2

2

2

3

4

4

5

5

Виды перевода (художественный, научно-технический, общественно-политический).

Методы перевода. Метод сегментации текста - письменный перевод; метод записи - последовательный перевод; метод трансформации исходного текста - синхронный перевод.

Жанры текстов и их учёт при переводе. Перевод профессионально ориентированных текстов.

Усложненные структуры

(конструкции) в составе предложения.

Технология предпереводческого анализа.

Аспекты предпереводческого анализа.

Лексические, синтаксические средства, характерные для каждого типа текста.

Стилистические и грамматические средства, характерные для каждого типа текста.

Составление резюме.

Традиционная.

Анализ текстов (определение вида перевода). Перевод текстов с использованием разнообразных методов.

Интерактивная.

Case-study

(анализ конкретных ситуаций).

Традиционная.

Определение жанров представленных текстов.

Перевод с иностранного языка на русский и с родного языка на иностранный. Выполнение упражнений.

Традиционная.

Выполнение упражнений.

Интерактивная. ПОПС

(позиция-обоснование-примерследствие).

Традиционная.

Анализ представленных текстов.

Выявление лексических и синтаксических средств.

Традиционная. Анализ представленных текстов.

Выявление стилистических и грамматических средств.

Научная статья. Аннотирование и реферирование.

Аннотация. Виды аннотации.

Аннотирование профессиональноориентированных текстов.

Моя научная работа.

Интерактивная.

Деловая игра.

Сообщение (монологическое высказывание профессионального характера в объеме не менее 15-18 фраз за 5 минут в нормальном среднем темпе речи).

Традиционная.

Составление плана, тезисов.

Традиционная.

Составление аннотаций.

Лексические единицы и речевые образцы, необходимые для составления обоснования по теме диссертации.

Интерактивная.

«Внутренняя дидактическая беседа».

Традиционная.

Составление плана исследования.

Традиционная.

Реферирование текстов научного характера.

1

1

2

1

1

2

1

1

1

2

6

14-16

16

17-18

6

6

7

Деловая переписка. Правила составления деловых писем.

Интерактивная

. Составление деловых писем. Творческие задания (деловая игра).

Выполнение упражнений.

Деловая переписка.

Составление мотивированного письма. Виды сложных предложений.

Традиционная.

Составление мотивированного письма.

Выполнение упражнений.

Деловое общение по телефону. Традиционная.

Составление тематического диалога.

Интерактивная

. Ролевая игра.

2

1

2

19-20

21

22

23-24

7

8

8

8

Деловой этикет общения по телефону. Правила делового общения.

Международное научное сотрудничество. Умение речевого общения: прием зарубежных специалистов.

Международное научное сотрудничество. Обмен информацией профессионального характера.

Новые лексические единицы и речевые образцы по теме.

Международное научное сотрудничество. Научная конференция.

Интерактивная.

Круглый стол.

Анализ конкретных ситуаций.

Интерактивная. Ролевая игра.

Составление анкеты для обучения в России.

Интерактивная.

Разработка программы профессионального обмена для преподавателей.

Интерактивная.

Слайдпрезентация своей научной работы.

6. Самостоятельная работа студентов

Таблица 4

№ Наименование раздела дисциплины

Вид самостоятельной работы

1 Стратегии устного и письменного перевода.

Перевод профессионально-ориентированных текстов. Формальные признаки сложного дополнения (Complex Object). Написание эссе.

2 Аннотирование и реферирование.

Аннотирование профессиональноориентированных текстов. Составление плана

3 Резюме.

4 Деловая переписка.

Моя научная работа. тезисов.

Составление резюме. Реферирование текстов научного характера.

Составление деловых и мотивированных писем.

5 Деловое общение по телефону.

Написание реферата. Запрос информации.

Оформление и размещение заказа. Решение проблем.

2

1

2

1

Трудоемкость

(в академических часах)

18

18

18

18

18

7

6

Международное научное сотрудничество.

Аннотирование направленности. текстов профессиональной

12

7. Компетентностно-ориентированные оценочные средства

7.1. Оценочные средства диагностирующего контроля

Грамматический тест, чтение, обсуждение и аннотирование текста общекультурного характера.

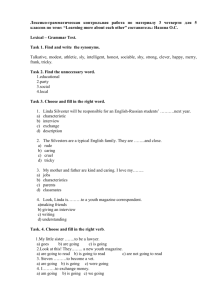

Образец диагностирующего грамматического теста.

Choose the right form of the verb:

1.

Who speaks French in your family? – I … a. have b. do c. am

2.

When … you buy the new TV set? a. did b. were c. are

3.

We … never been to London. a. had b. were c. have

4.

Where … you going when I met you last night? a. did b. were c. are

5.

… your friend like to watch TV in the evening? a. do b. does c. is

6.

What are you doing? – I … reading a book. a. was b. am c. is

7.

We thought they … be late. a. would b. shall c. will

8.

Many new buildings … built in our town last year. a. had b. were c. were

9.

The letter … sent tomorrow. a. will be b. has c. will

10.

I … Dick today. a. haven’t seen b. hadn’t seen c. didn’t see

11.

Were you tired after skiing yesterday? – Yes, I … a. were b. did c. was

12.

When we came into the hall they … this problem. a. were discussing b. discussed c. have discussed

13.

We … from institute in five years. a. have graduated b. graduated c. shall graduate

14.

Don’t go out. It … hard. a. is raining b. was raining c. rains

15.

They … the institute three years ago. a. have entered b. entered c. had entered

16.

Does the professor … a lot of experience? a. has b. have c. had

17.

Did he … the week-end in the country? a. spent b. spend c. spends

18.

I shall ring you up as soon as I … home.

8

a. came b. shall come c. come

19.

The report … ready by 6 o’clock yesterday. a. was b has been c. had been

20.

She usually … to bed very early. a. goes b. has gone c. going

Образец текста общекультурного характера для чтения, обсуждения и аннотирования.

A Brief History of Oxford city

Oxford was founded in the 9th century when Alfred the Great created a network of fortified towns called burhs across his kingdom. One of them was at Oxford. Oxford is first mentioned in 911 in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

According to legend, Oxford University was founded in 872 when Alfred the Great happened to meet some monks there and had a scholarly debate that lasted several days. In reality, it grew up in the 12th century when famous teachers began to lecture there and groups of students came to live and study in the town.

But Oxford was a fortress as well as a town. In the event of war with the Danes all the men from the area were to gather inside the burgh. However this strategy was not entirely successful. In

1009 the Danes burned Oxford. However Oxford was soon rebuilt. In 1013 the Danish king claimed the throne of England. He invaded England and went to Oxford. In 1018 a conference was held in

Oxford to decide who would be the king of England.

By the time of the Norman Conquest, there were said to be about 1,000 houses rn Oxford, which meant it probably had a population of around 5,000. By the standards of the time, it was a large and important town (even London only had about 18,000 inhabitants). Oxford was the 6th largest town in England. Oxford probably reached its zenith at that time. About 1072 the Normans built a castle at

Oxford.

In the 12th and 13th centuries Oxford was a manufacturing town. It was noted for cloth and leather. But in the 14th and 15th centuries manufacturing declined. Oxford came to depend on the students. It became a town of brewers, butchers, bakers, tailors, shoemakers, coopers, carpenters and blacksmiths. In the later Middle Ages Oxford declined in importance.

In the 16th century Oxford declined further in terms of national importance, though it remained a fairly large town by the standards of the time. Oxford was economically dependent on the university.

The students provided a large market for beer, food, clothes and other goods.

From 1819 Oxford had gas street lighting.

In the late 19th century a marmalade making industry began in Oxford. There was also a publishing industry and an iron foundry.

Oxford gained its first cinema in 1910.

The fate of Oxford was changed in 1913 when a man named Morris began making cars in the city. In 1919 a radiator making company was formed. By the 1930s Oxford was an important manufacturing centre. It was also a prosperous city., Furthermore it escaped serious damage during

World War II.

Oxford airport opened in 1938.

Today the main industries are still car manufacturing and making vehicle parts and publishing.

Today the population of Oxford is 121,000.

Questions:

1. When was Oxford founded?

2. Who created network of fortified towns called burghs?

3. When was Oxford mentioned for the first time?

4. When was Oxford University founded?

5. What happened to Oxford in 1009?

9

6. What population had Oxford by the time of the Norman Conquest of 1086?

7. When did Oxford reach its zenith?

8. When did Oxford become a manufacturing town?

9. When did Oxford decline in importance?

10. When did Oxford gain its gas street lighting?

11. Was Oxford economically dependent on the University or not?

12. When did Oxford gain its first cinema?

13. Who changed the fate of the town in 1913?

14. How many people live in Cambridge nowadays?

7.2. Оценочные средства текущего контроля: модульно-рейтинговая технология оценивания работы студентов

7.2.2. Оценивание аудиторной работы студентов (не предусмотрено)

Таблица 6

№ Наименование раздела дисциплины

Формы оцениваемой работы

Работа на практических занятиях

Максима льное кол-во баллов

1

2

3

4

5

6 Моя научная работа.

7

Стратегии устного и письменного перевода.

Вида и методы перевода.

Жанры текстов и их учёт при переводе. Перевод профессионально ориентированных текстов.

Технология предпереводческого анализа.

Составление резюме.

Итого

Научная статья.

Аннотирование и реферирование.

Аннотация. Виды аннотации.

Итого

Деловая переписка.

6 семестр

Анализ текстов (определение вида перевода). Перевод текстов с использованием разнообразных методов.

Case-study (анализ конкретных ситуаций). Перевод с иностранного языка на русский и с родного языка на иностранный. Выполнение упражнений.

Выполнение упражнений. ПОПС

(позиция-обоснование-примерследствие). Анализ текстов.

Сообщение (монологическое высказывание профессионального характера в объеме не менее 15-18 фраз за 5 минут в нормальном среднем темпе речи).

6 семестр

Составление плана, тезисов.

Составление аннотаций.

23

26

25

74

19

18

«Внутренняя дидактическая беседа».

Составление плана исследования.

Реферирование текстов научного характера.

20

57

7 семестр

Составление деловых и мотивированных писем. Дискуссии. Творческие задания.

Выполнение упражнений.

19

Модуль

(аттеста ция)

1

2

3

1

2

3

1

10

8

Деловое общение по телефону. Деловой этикет общения по телефону.

9

Правила делового общения.

Итого

10

Международное научное сотрудничество. Умение речевого общения: прием зарубежных специалистов.

Обмен информацией профессионального характера.

11 Международное научное сотрудничество.

12

Научная конференция.

Итого

Аннотирование текстов профессиональной направленности.

Составление тематического диалога.

Ролевая игра.

Анализ конкретных ситуаций.

19

19

57

8 семестр

Ролевая игра. Составление анкеты для обучения в России. Разработка программы профессионального обмена для преподавателей.

Слайд-презентация своей научной работы.

Круглый стол.

19

19

19

57

7.2.3. Оценивание самостоятельной работы студентов

Таблица 7

№

1

2

3

4

Наименование раздела

(темы) дисциплины

Стратегии устного и письменного перевода.

Стратегии устного и письменного перевода.

Аннотирование и реферирование.

Итого

Резюме.

5 Деловое общение по телефону.

6

Моя научная работа.

Итого

Формы оцениваемой работы

6 семестр

Перевод профессиональноориентированных текстов.

Формальные признаки сложного дополнения (Complex Object). Написание эссе.

Аннотирование профессиональноориентированных текстов. Составление плана тезисов.

26

7семестр

Составить резюме.

Написание реферата.

Максима льное кол-во баллов

7

9

10

12

12

19

7

8

9

Деловая переписка.

Профессиональная сфера общения.

Международное

Реферирование текстов научного характера.

23

8 семестр

Составление деловых и мотивированных писем.

Составление резюме. Интервью об устройстве на работу.

Аннотирование текстов профессиональной

12

12

19

2

3

1

2

3

Модуль

(аттеста ция)

1

2

3

1

2

3

1

2

3

11

научное сотрудничество.

Итого направленности.

23

8 семестр

10 Структура научной работы.

11 Написание доклада.

Разбор структуры научной работы.

Изучение научных терминов, клише, фразовых единиц.

Презентация научного доклада.

12 Защита научного доклада.

Итого

43

7.2.4. Оценочные средства для текущего контроля успеваемости

12

12

19

1

2

3

7.2.4.1. Составление словаря

Список слов для составления словаря заказное письмо, обыкновенная телеграмма, бланк телеграммы, адрес, срочная телеграмма, международная телеграмма, электронное письмо, индекс, послание, почта, почтовый, сообщение, почтовый офис, почта, подпись, отправлять по почте, принять к сведению содержание письма, получать письмо, отправлять письмо, печатать письмо, получатель, адресат, авиапочта, проспект, бульвар, деловое письмо, корреспонденция, переписка, район, набережная, конверт, шоссе, личное\неформальное письмо, переулок, почтовый ящик, официальное письмо, бандероль, посылка, область, отправитель, марка, край, адрес получателя, адрес отправителя и др.

7.2.4.2. Составление письменных документов

Изучение структуры письменных документов, стандартных фраз, употребляемых в этих видах документов, составление аналогичных документов.

Образец:

Уважаемый г-н Футман!

Я позволил себе послать Вам этот факс вместо того, чтобы беспокоить Вас по телефону.

На прошлой неделе я отправил Вам короткое предложение. Хотелось бы знать, соответствует ли оно интересам Вашей компании.

Мы хотели бы сотрудничать с Вами и были бы благодарны, если бы Вы сообщили нам как можно скорее, вписывается ли в Ваши планы это сотрудничество.

С уважением

Dear Mr. Footman:

I am taking the liberty of writing you this fax instead of interrupting you by phone.

Last week I mailed you a brief proposal. Now I am wondering if it suits your company's needs.

We wish to do business with you and would appreciate it if you would let us know as soon as possible if we fit into your plans.

Sincerely yours,

7.2.4.3. Творческие задания

1) Составить письмо-запрос о возможности учебы в высшем учебном заведении.

2)

Составить письмо рекомендательного характера; письмо с просьбой о предоставлении работы и ответ на данную просьбу.

3)

Разработать структуру деловых переговоров (объект по выбору).

4) Провести анализ научных текстов.

Образец диагностирующего грамматического теста.

12

Составление аннотации, плана/тезисов текстов и выполнение упражнений по ним.

7.2.4.4.

Образец контрольного научно-профессионального текста для анализа, составления плана, аннотирования и выполнения упражнений по нему.

THE ECONOMETRICS SYSTEM by William J. Reynolds

Last year Lawrence R. Klein, professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania, became the ninth American to win the Nobel Prize in Economics since the category's inception in

1968. Klein's prize, and its $215,000 purse, was awarded for no single endeavor, but for Klein's trailblazing efforts in the refinement and further development of the economic device call econometrics.

No, econometrics doesn't seek to determine the ramifications of converting to grams and liters.

Econometrics is perhaps best thought of as a tool by which economic theories-abstract ideas — are empirically tested and expressed in quantitative terms (i.e., hard numbers).

While the roots of econometrics can be traced to the 1830s (in such works as Antoine Augustin

Coumot's «Recherches surles principes mathematiques de la theorie des richesse», 1938), the seminal work came about in the 1930s. With the world economy in the grip of a monumental global depression, the need for developing a way to accurately predict the effects of economic policy became obvious. Jan Tinberg of the Netherlands established much of the groundwork then, examining the inter dependence of separate factors — variables such as productivity, consumption, employment, national income, retail prices and the usual economic catch phrases — within an economic system, and even beyond: who can dispute that the policies enacted in the other economies affect our own?

For his work Tinberg was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1969, but it is Lawrence Klein who is acknowledged as having made the first practical application of econometrics in the 1950s, by using modem computer-coded tools of statistical analysis to verify Tinberg's idea of interrelationship and to express those relationships quantitatively, in terms of mathematical formulae.

These formulae are arrived at by painstaking recording the historical movements of goods and services throughout an economy's various sectors — government, capital formation, household goods, etc. The historical relationships of these sectors are studied and applied to the construction of equations that attempt to forecast, for instance, how a given change in total after-tax income, coupled with a change in wholesale prices, is likely to affect consumption.

Basic cause-and-effect, right? But it takes a comprehensive set of equations to account for all of the significant variables and what will happen to them all — simultaneously — if something changes.

This set composes an econometric model and, since the model is only as good as the data it can accommodate, a valid model must contain literally scores of formulae. At Pennsylvania, Klein works with a model that strives to describe the total global economy — and which contains over 1,000 individual variables.

Lately the validity of existing econometric models — specifically, their forecasting abilities — has been questioned. The severity of recent economic occurrences such as the 1974 recession and the significant inflation of a year ago were not indicated in the forecasts. There is concern among some economists that the historical assumptions on which current econometrics is based may no longer be wholly applicable.

Nonetheless, economists and those who rely on economic information are in no hurry to disavow themselves of any association with econometrics. Just last year, Business Week was publishing regular quarterly forecasts based on information retrieved from Klein's system-model.

Econometric predictions might not be letter-perfect, but they're the best predictions available, at least by dint of being the only ones available.

And since economists, like meteorologists, will forever be called upon to make predictions, they will forever seek to fine-tune, improve and even reinvent their going-out-on-a-limb tools. If there's such a thing as perpetual motion, this must surely be it.

13

No wonder economics is called the dismal science.

Exercises:

1. This article can be divided into five sections. The paragraph divisions for sections I and II and the sub-titles for sections I and V are given below. Fill in the missing paragraph numbers and sub-titles.

I. Term «Econometrics» Introduced 1

II.___________________________ 2

III.__________________________ __

IV.__________________________ __

V. Current Status of Econometrics __

2. Fill in the empty spaces in the table below, giving date, name, and contribution to the history of econometrics.

Date

1930s

Name

Lawrence Klein

Contribution to the history of Econometrics

Recherches sur les principes mathematiques de la theorie de richesse

3. What caused Jan Tinberg to develop his theory? a.

the research ofAugustin Coumot b.

the depression of the 1930"s c. the interdependence of economic variables d. the effects of other economic systems on our own

1.

What word in the text means the same as «factors» (1.21)?________

5. Klein's econometric model contains over 1,000 variables because a.

there are 1,000 significant variables in economics b.

the validity of the model depends upon its completeness c.

the model attempts to forecast the economy of the entire world. d. the validity of econometrics has been questioned

6.

In paragraph 6, Reynolds gives a definition of econometrics.

In what earlier paragraph has he also given a definition of econometrics? ____

7.

The current opinion of econometrics held by the experts is that a.

it contains over 1,000 variables b.

it is valid for forecasting economic changes c.

it is based on assumptions which are no longer valid d.

although it is not perfect, it is the only economic forecasting tool available.

7.3 Оценочные средства промежуточной аттестации

7.3.2. Оценочные средства для промежуточной аттестации

7.3.2.1. Перечень вопросов для зачёта

1. Жанры текста. Перевод текста и его аннотация.

2. Моя научная деятельность.

14

3. В поисках работы. Составление резюме.

4. Деловое письмо. Виды деловых писем.

5. Реферирование текста научного характера.

6. Реферирование публицистического текста.

7. Деловое общение, его виды и формы. Составить диалог.

8. Аннотирование и реферирование текста профессиональной направленности.

7.3.2.2. Перечень вопросов к экзамену

1. Перевод публицистического текста и составление аннотации.

2. Моя научная деятельность. Написание эссе.

3. Резюме. Основные части резюме. Написать резюме.

4. Виды и формы деловой переписки.

5. Реферирование текста научного характера.

6. Деловое общение, его виды и формы. Составить диалог.

7. Аннотирование и реферирование текста профессиональной направленности.

8. Составление мотивированного письма.

9. Подготовка вопросов для интервью об устройстве на работу.

10. Составление делового письма.

11. Презентация тезисов своего научного исследования.

8. Учебно-методическое и информационное обеспечение дисциплины а) основная литература:

1.

Агабекян, И.П. Английский для менеджеров / И.П. Агабекян. – Ростов н/Д: Феникс, 2011.

2.

Казакова, Т.А. Практические основы перевода / Т.А. Казакова.- СПб: Изд-во «Союз», 2010.

3.

Крупнов, В.Н. Гуманитарный перевод: учебное пособие для вузов по специальности

«Перевод и переводоведение» / В.Н. Крупнов. – М.: Академия, 2011.

4.

Шевелева, С.А. Деловой английский / С.А. Шевелева. – М.: ЮНИТИ, 2010. б) дополнительная литература:

1.

Басс, Э.М. Научная и деловая корреспонденция / Ю.М. Басс. – М.: Наука, 1991.

2.

Бреус, Е.В. Теория и практика перевода с английского языка на русский / Е.В. Бреус. – М.:

Изд-во УРАО, 2001.

3.

Гринев, С. В. Введение в терминоведение / С.В. Гринев. – М.: Московский лицей, 1993.

4.

Кондратюкова, Л.К., Ткачева, Л.Б., Акулинина, Т.В. Аннотирование и реферирование английской научно-технической литературы / Л.К. Кондратюкова, Л.Б. Ткачева, Т.В.

Акулинина. – Омск, 2001.

5.

Мердок-Стерн, С. Деловые приемы и встречи на английском: визиты, сотрудничество, профессиональные контакты: учебное пособие / С. Мердок-Стерн. – М.: АСТ, 2007.

6.

Прохоров, Ю.Е. Действительность. Текст. Дискурс / Ю.Е. Прохоров. – М.: Флинта, 2011.

7.

Рубцова, М.Г. Чтение и перевод английской научной и технической литературы / М.Г.

Рубцова. – М.: Астрель, АСТ, 2004.

8.

Сафроненко, О.И. Английский язык для магистров и аспирантов естественных факультетов университетов / О.И. Сафроненко. – М.: Высшая школа, 2005.

9.

Сулейманова, О.А., Беклемешева, Н.Н. Грамматические аспекты: уч. пособие для студ. вызов

/ О.А. Сулейманова, Н.Н. Беклемешева. – М.: Академия, 2010.

10.

Шеллов, С.Д. Определение терминов и понятийная структура терминологии / С.Д. Шеллов.

– СПб, 1998.

15

11.

Hashemi, L., Murphy, R. English Grammar in Use. Supplementary Exercises / L. Hashemi, R.

Murphy. – Cambridge: Univ. Press, 2001.

12.

Murphy, R. Essential Grammar in Use / R. Murphy. – Cambridge: Univ. Press, 2000.

13.

Murphy, R. Essential Grammar in Use (for Intermediate students) / R. Murphy. – Cambridge:

Univ. Press, 2001.

14.

Swan, M., Walter, C. How English works. A Grammar Practice Book / M. Swan, C. Walter. –

Oxford: Univ. Press, 2000. в) периодические издания:

1.

Периодическое издание газеты «Moscow News».

2.

Приложение к газете «Первое Сентября» «English». г) интернет-ресурсы: http://www.learnenglish.de/ http://dictionary.reference.com/ http://learnenglish.britishcouncil.org/en/ http://usefulenglish.ru/ http://lengish.com/ http://www.native-english.ru/ http://www.study.ru/ http://www.mystudy.ru/ http://4flaga.ru/material.html http://englishouse.ru/index.html http://www.usingenglish.com/ http://www.bbc.co.uk/learning/ http://www.britishcouncil.org/new/learning/ http://www.cambridge.org/learning/ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page http://elt.oup.com/?cc=ru&selLanguage=en http://www.merriam-webster.com/ http://www.macmillandictionary.com/ http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/news/ http://www.guardian.co.uk/ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/

д) мультимедийные средства:

CD «ABBYY Lingvo 9.0»

CD 1, 2 «Т.Н. Игнатова. English for Communication»

CD «Professor Higgins. Английский без акцента»

CD «English platinum»

CD «Oxford Platinum»

9. Материально-техническое обеспечение дисциплины

Минимально необходимый перечень материально-технического обеспечения включает: лингафонный кабинет, компьютерные классы с выходом в сеть Интернет, аудитории, специально оборудованные мультимедийными демонстрационными комплексами, учебнометодический ресурсный центр, методический кабинет или специализированную библиотеку.

Реализация дисциплины предусматривает использование учебно-наглядных пособий: фонетические, грамматические таблицы, тематические плакаты (по лексике), географические карты. Средства обучения включают в себя учебно-справочную литературу (рекомендованные учебники и учебные пособия, словари), учебные и аутентичные печатные, аудио- и видеоматериалы, Интернет-ресурсы.

16

10. Паспорт рабочей программы дисциплины

Разработчик(и) : Морозова Е.Н., к.п.н., доцент, Касимова Т.Н., к.п.н., доцент

Программа одобрена на заседании кафедры иностранных языков и МП от «___»_______________г., протокол №________

Согласовано:

Зав. кафедрой ______________________Вычужанина А.Ю.

«___» ________________г.

Согласовано:

Специалист по УМР _________________

«___» ________________г.

Приложение 1

17

Методические указания по дисциплине «Иностранный язык в профессиональной коммуникации»

Структура программы отражает основные дидактические принципы обучения: от простого к сложному, последовательность, повторяемость, контроль. Она способствует

18

достижению конечной цели обучения – выработке у студентов навыков и умений практического владения компетенциями делового общения на английском языке в рамках деятельности, определяемой направлением подготовки.

Дисциплина «Деловой иностранный язык» опирается на теоретические и практические знания иностранного языка, полученные студентами на предыдущем этапе изучения языка в академии. В процессе изучения дисциплины обобщаются, систематизируются, корректируются и дополняются приобретенные ранее знания магистров по иностранному языку, даются основы для дальнейшего самостоятельного изучения языка. Все правила и понятия должны формулироваться в максимально простой и четкой форме, иллюстрироваться простыми и наглядными примерами.

В процессе формирования более сложных грамматических навыков следует опираться на интерактивные и коммуникативные формы обучения, что способствует ускоренному формированию практических навыков делового общения. Необходимо сочетать фронтальную, индивидуальную, парную и групповую формы работы с тем, чтобы каждый студент был вовлечен в различные виды языковой деятельности.

Во время обучения в магистратуре значительно повышается роль самостоятельной творческой работы студентов, большее место на занятиях отводится творческим формам речевого общения: диалогам, ролевым играм, деловым диспутам. Интерактивные игры обладают высокой степенью наглядности и позволяют активизировать изучаемый языковой материал в речевых ситуациях, моделирующих и имитирующих реальный процесс профессионального общения.

Содержание курса отражает определенные вопросы деловой сферы общения, в которой будущие специалисты будут выполнять свои профессиональные задачи путем реализации навыков и умений, приобретенных в процессе обучения.

В процессе обучения цели совершенствования языковой компетенции сочетаются с задачами совершенствования личностных качеств студентов. Материалы, составляющие учебные пособия, подобраны таким образом, что они способствуют развитию мыслительных способностей студентов, формированию у них навыков самообразования.

Для обеспечения высокого уровня овладения изучаемым материалом и закрепления его на практике используются интерактивные методы обучения. В основу построения данного курса положена ситуативно-тематическая организация учебного материала, что предполагает максимальное включение студентов в естественный процесс взаимодействия в виде беседы, диалога, обмена мнениями, информацией. Наиболее широко используются следующие интерактивные методы: ролевые/деловые игры, дискуссии, направленные на моделирование и воспроизведение профессионально ориентированных ситуаций, вовлечение в мыслительный поиск и коммуникацию всех обучающихся. Интерактивные методы способствуют повышению мотивации студентов, создают возможности для самовыражения, овладения изучаемым материалом на практике и ведут к повышению уровня компетентности в профессиональной сфере.

Конечной целью обучения студентов является практическое овладение деловым общением. После завершения курса обучения магистры должны:

владеть интонационными моделями делового речевого этикета;

владеть устной диалогической и монологической речью в профессиональной сфере;

знать основные стратегии и особенности научно-технического перевода;

знать сложные грамматические структуры, необходимые для более точного перевода и понимания текстов научного и профессионального характера;

уметь вести беседу, в том числе оn-line, о своей будущей профессиональной деятельности, планах и научных проектах в профессиональной карьере;.

владеть терминологическим вокабуляром, фразеологизмами (пословицами, поговорками, идиомами) в рамках сферы профессионально-делового общения;

уметь составлять резюме;

19

аннотировать изучаемые тексты, статьи и др. материалы в контексте сферы научного и профессионального общения;

уметь писать и отправлять электронные письма с учетом речевого и делового этикета, в рамках сферы профессионального общения.

При аннотировании и реферировании текстов общекультурного, научного и профессионального характера, студентам придется столкнуться с лексикой английского языка, которая делится на три категории: общеупотребительные слова, составляющие основу языка; слова и словосочетания научного регистра речи, т.е. общенаучная лексика; собственно термины.

Следует обратить внимание на то, что научные термины в значительной части интернациональны.

В научных текстах превалируют заголовки номинативного типа, в которых нередко формулируется проблема, изложенная в статье, эссе, монографии, книге. Эта проблема последовательно раскрывается от известного к неизвестному. Внешним признаком научного стиля текста является порядок организации информации. Текст имеет введение, содержащее основной тезис, главную часть, в которой дается аргументация тезиса и практическое описание нового изобретения, проведенного эксперимента, значимых теоретических и практических выводов. Заключительная часть/послесловие выполняет итоговую интегрирующую функцию.

Специфической чертой научного текста являются подчеркнутая логичность, многократное повторение с дополнительным аргументированием, сложный синтаксис и многообразие профессионально ориентированной тематики.

В научно-техническом тексте широко используются штампы (часто повторяющиеся текстовые и речевые обороты) и клише (устойчивые словосочетания, постоянно используемые в типичных контекстах).

Для научно-технического текста на английском языке характерны глагольные фразеологические сочетания: to make mention of (упоминать), to make use of (использовать), to pay attention to (обращать внимание на), to take advantage of (воспользоваться), а также глаголы с послелогами: to interact with (взаимодействовать), to deal with (иметь дело с), to refer to

(ссылаться на) , to depend on (зависеть от).

Этапы работы с научно-техническим тексом: просмотр научно-технического текста или статьи, ознакомление с содержанием, поиск нужной информации, детальное изучение языка и содержания.

Анализ в процессе чтения научно-технической литературы связан, прежде всего, с лексическими и стилистическими уровнями текста. На лексическом уровне объектом анализа для читающего и изучающего деловой язык становится главным образом незнакомая лексика, лексические единицы, встречающиеся в контекстуальном значении, специфические авторские обороты речи. В арсенале изучающего иностранный язык имеются такие виды работы, как использование словарей, перефразирование (то есть подбор так называемых эквивалентных замен, синонимичных средств выражения), толкование значения и смысла текста.

Для качественного и глубокого понимания научно-технического текста студентам целесообразно пользоваться энциклопедическим словарем, представляющим в кратком виде современное состояние научного знания. Специальным видом энциклопедического словаря является отраслевой словарь, содержащий информацию, касающуюся только какой-либо определенной отрасли. Каждая отрасль науки, развиваясь, формирует свой специфический язык, обладающий семантической определенностью для однозначности всех понятий данной науки.

Рекомендации студентам для самостоятельной работы с текстами научного и профессионального характера:

Сегментировать текст. Предварительная сегментация текста подразумевает выделение в тексте таких фрагментов, перевод которых не зависит от контекста. При этом необходим перевод не фрагментов научного текста, а фрагментов смысла.

20

Учитывать многозначность слов. Большинство слов в английском языке являются полисемантическими, поэтому перевод слова и его интерпретация осуществляются в соответствии с контекстом.

Учитывать способы словообразования. Знание словообразования является эффективным средством расширения научного и профессионального словаря. Умение разобрать производное слово на корень, суффикс и префикс позволяет определить значение неизвестного слова.

Учитывать эквивалентность. Сопоставляя лексику двух языков, часто можно обнаружить пробелы в семантике одного из них, т.е., безэквивалентные единицы языка.

Необходимо проанализировать слово (словосочетание), его окружение и раскрыть смысл путем интерпретации.

Использовать межъязыковые и внутриязыковые трансформации как способ эффективного объяснения смысла структуры, предшествующего ее сравнению с эквивалентной ей структурой русского языка. Необходимо подбирать синонимы, интерпретировать сложные описательные обороты, выделять слова с ключевой информацией, перефразировать длинные сентенции и находить лексические опорные единицы для запоминания.

21

Приложение 2

Практические занятия по курсу «Иностранный язык в профессиональной коммуникации»

22

Важное значение в подготовке студента к профессиональной деятельности имеют практические занятия. Они составляют значительную часть всего объёма аудиторных занятий и имеют важнейшее значение для усвоения программного материала. Выполняемые на них задания можно подразделить на несколько групп. Одни из них служат иллюстрацией теоретического материала и носят воспроизводящий характер. Они выявляют качество понимания обучающимися теории. Другие представляют собой образцы задач и примеров, разобранных в аудитории.

Следующий вид заданий содержит элементы творчества. Одни из них требуют от обучающегося преобразований, реконструкций, обобщений. Для их выполнения необходимо привлекать ранее приобретенный опыт, устанавливать внутрипредметные и межпредметные связи. Решение других требует дополнительных знаний, которые обучающийся должен приобрести самостоятельно. Третьи предполагают наличие у обучающегося некоторых исследовательских умений.

Практические занятия не только углубляют и закрепляют соответствующие знания, но и развивают инициативу, творческую активность, вооружают будущего специалиста методами и средствами научного познания.

Тема1. Стратегии устного и письменного перевода. Методы перевода.

План:

1. Виды перевода.

2. Методы перевода.

3. Жанры текстов и их учёт при переводе. Усложненные структуры (конструкции) в составе предложения.

Литература:

1. Казакова, Т.А. Практические основы перевода / Т.А. Казакова. – СПб: Изд-во «Союз», 2007.

2. Крупнов, В.Н. Гуманитарный перевод: учебное пособие для вузов по специальности

«Перевод и переводоведение» / В.Н. Крупнов. – М.: Академия, 2009.

3. Прохоров, Ю.Е. Действительность. Текст. Дискурс / Ю. Е. Прохоров. – М.: Флинта, 2011.

4. Murphy, R. Essential Grammar in Use (for Intermediate students) / R. Murphy. – Cambridge: Univ.

Press, 2001.

5.Swan, M., Walter, C. How English works. A Grammar Practice Book / M. Swan, C. Walter. –

Oxford: Univ. Press, 2000.

При подготовке к практическому занятию необходимо использовать рекомендованную литературу, а также материалы сайта www.wikipedia.com

При подготовке к пунктам 1 и 2 рассмотрите виды перевода (художественный, научнотехнический, общественно-политической) и методы перевода (метод сегментации текста - письменный перевод; метод записи - последовательный перевод; метод трансформации исходного текста - синхронный перевод). В пункте 3 рассмотрите жанры текстов, а также усложненные структуры (конструкции) в составе предложения: 1) формальные признаки цепочки определений в составе именной группы (наличие нескольких левых определений между детерминативом существительного и ядром именной группы); 2) формальные признаки сложного дополнения (Complex Object).

Тема 2: Технология предпереводческого анализа.

План:

1. Лексические, синтаксические, стилистические и грамматические средства.

2. Формальные признаки логико-смысловых связей между элементами текста.

Литература:

23

1. Казакова, Т.А. Практические основы перевода / Т.А. Казакова. – СПб: Изд-во «Союз», 2007.

2. Крупнов, В.Н. Гуманитарный перевод: учебное пособие для вузов по специальности

«Перевод и переводоведение» / В.Н. Крупнов. – М.: Академия, 2009.

3. Прохоров, Ю.Е. Действительность. Текст. Дискурс / Ю. Е. Прохоров. – М.: Флинта, 2011.

4. Сулейманова, О.А., Беклемешева, Н.Н. Грамматические аспекты: уч. пособие д/студ. вызов /

О.А. Сулейманова, Н.Н. Беклемешева. – М.: Академия, 2010.

5. Бреус, Е.В.Теория и практика перевода с английского языка на русский / Е.В. Бреус. – М.:

Изд-во УРАО, 2001.

6. Hashemi, L., Murphy, R. English Grammar in Use. Supplementary Exercises / L. Hashemi, R.

Murphy.

–

Cambridge: Univ. Press, 2001.

При подготовке к практическому занятию необходимо использовать рекомендованную литературу, а также материалы сайта www.wikipedia.com

При подготовке к пункту 1 необходимо рассмотреть лексические, синтаксические, стилистические и грамматические средства, характерные для следующих типов текста: научного, научно-технического, специального. В пункте 2 рассмотрите логико-смысловые связи между следующими элементами текста: союзы, союзные слова, клишированные фразы, вводные обороты и конструкции, слова-сигналы ретроспективной (местоимения) и перспективной (наречия) связи, а также определите формальные признаки конструкции

"именительный падеж с инфинитивом".

Тема 3. Составление резюме.

План: Основные части резюме: 1) личная информация; 2) цель; 3) образование; 4) профессиональный опыт; 5) специальные навыки; 6) рекомендации.

Литература:

1. Мердок-Стерн, Серена Деловые приемы и встречи на английском: визиты, сотрудничество, профессиональные контакты: учебное пособие / Серена Мердок-Стерн. – М.: АСТ, 2007.

2. Шевелева, С.А. Деловой английский / С.А. Шевелева. – М.: ЮНИТИ, 2007.

3. Басс, Э.М. Научная и деловая корреспонденция / Ю.М. Басс. – М.: Наука, 1991.

4. Сафроненко, О.И. Английский язык для магистров и аспирантов естественных факультетов университетов / О.И. Сафроненко. – М.: Высшая школа, 2005.

При подготовке к практическому занятию необходимо использовать рекомендованную литературу. Рассмотреть структуру написания резюме и представить свое в виде сообщения

(монологическое высказывание профессионального характера в объеме не менее 15-20 фраз).

Тема 4. Научная статья. Аннотирование и реферирование.

План:

1. Аннотация. Виды аннотаций.

2. Научный стиль.

Литература:

1. Кондратюкова, Л.К., Ткачева, Л.Б., Акулинина, Т.В. Аннотирование и реферирование английской научно-технической литературы / Л.К. Кондратюкова, Л.Б. Ткачева, Т.В.

Акулинина. – Омск, 2001.

2. Рубцова, М.Г. Чтение и перевод английской научной и технической литературы / М.Г.

Рубцова. – М.: Астрель, АСТ, 2004.

При подготовке к практическому занятию необходимо использовать рекомендованную литературу, а также материалы сайта www.wikipedia.com

При подготовке к пункту 1 необходимо рассмотреть основные характеристики

24

аннотации и ее виды. В пункте 2 дайте определение научного стиля, рассмотрите его особенности и историю, общие черты, а также виды и жанры научного стиля; особое внимание обратите на языковые средства, используемые в научном стиле.

Тема 5. Моя научная работа.

План: Лексические единицы и речевые образцы, необходимые для составления обоснования по теме диссертации.

Литература:

1. Кондратюкова, Л.К., Ткачева, Л.Б., Акулинина, Т.В. Аннотирование и реферирование английской научно-технической литературы / Л.К. Кондратюкова, Л.Б. Ткачева, Т.В.

Акулинина. – Омск, 2001.

2. Рубцова, М.Г. Чтение и перевод английской научной и технической литературы / М.Г.

Рубцова. – М.: Астрель, АСТ, 2004.

При подготовке к практическому занятию необходимо использовать рекомендованную литературу, а также материалы сайта www.wikipedia.com

При подготовке к практическому занятию необходимо составить вокабуляр, включающий также и речевые обороты, которые помогут дать обоснование выбранной темы исследования и более подробно представить содержательную сторону исследуемой тематики.

Тема 6. Деловая переписка.

План:

1.

Правила составления деловых писем, мотивированного письма.

2.

Виды сложных предложений.

Литература:

1.

Басс, Э.М. Научная и деловая корреспонденция / Ю.М. Басс. – М.: Наука, 1991.

2.

Ступин, Л. П. Письма по-английски на все случаи жизни: Учебно-справочное пособие для изучающих английский язык / Л.П. Ступин. — СПб.: Просвещение, 1997.

3.

Сулейманова, О.А., Беклемешева, Н.Н. Грамматические аспекты: уч. пособие д/студ. вызов /

О.А. Сулейманова, Н.Н. Беклемешева. – М.: Академия, 2010.

4.

Murphy, R. Essential Grammar in Use (for Intermediate students) / R. Murphy. – Cambridge: Univ.

Press, 2001.

5.

Swan, M., Walter, C. How English works. A Grammar Practice Book / M. Swan, C. Walter. –

Oxford: Univ. Press, 2000.

При подготовке к практическому занятию необходимо использовать рекомендованную литературу. При подготовке к пункту 1 необходимо изучить этикет написания письма, ознакомиться с правилами составления деловых писем на английском языке, а также некоторыми правилами английской пунктуации и орфографии; составить список наиболее употребляемых выражений, используемых в начале и конце письма на основе анализа писем. В пункте 2 изучите вида сложных предложений, используемых в письмах, а также обратите внимание на использование сложных конструкций.

Тема 7. Деловое общение по телефону.

План:

1.

Деловой этикет общения по телефону.

2.

Правила делового общения.

Литература:

1. Агабекян, И.П. Английский для менеджеров / И.П. Агабекян. – Ростов н/Д: Феникс, 2011.

25

2. Мердок-Стерн, Серена Деловые приемы и встречи на английском: визиты, сотрудничество, профессиональные контакты: учебное пособие / Серена Мердок-Стерн. – М.: АСТ, 2007.

3. Шевелева, С.А. Деловой английский / С.А. Шевелева. – М.: ЮНИТИ, 2007.

4. http://www.usingenglish.com/

5. http://usefulenglish.ru/

6. http://www.native-english.ru/

При подготовке к практическому занятию необходимо использовать рекомендованную литературу и Интернет-ресурсы. При подготовке к данной теме дается определение понятию

«деловой этикет», изучается основа успешного проведения делового телефонного разговора и его структура, а также студент знакомится с репликами, способными скорректировать общение.

Тема 8. Международное научное сотрудничество.

План:

1. Умение речевого общения: прием зарубежных специалистов.

2. Обмен информацией профессионального характера. Новые лексические единицы и речевые образцы по теме.

3. Научная конференция.

Литература:

1.

Агабекян, И.П. Английский для менеджеров / И.П. Агабекян. – Ростов н/Д: Феникс, 2011.

2.

Казакова, Т.А. Практические основы перевода / Т.А. Казакова.- СПб: Изд-во «Союз», 2007.

3.

Мердок-Стерн, Серена Деловые приемы и встречи на английском: визиты, сотрудничество, профессиональные контакты: учебное пособие / Серена Мердок-Стерн. – М.: АСТ, 2007.

4.

Шевелева, С.А. Деловой английский / С.А. Шевелева. – М.: ЮНИТИ, 2007.

5.

Басс, Э.М. Научная и деловая корреспонденция / Ю.М. Басс. – М.: Наука, 1991.

6.

Сафроненко, О.И. Английский язык для магистров и аспирантов естественных факультетов университетов / О.И. Сафроненко. – М.: Высшая школа, 2005.

7.

http://www.usingenglish.com/

8.

http://usefulenglish.ru/

9.

http://www.native-english.ru/

10.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/learning/

11.

http://www.britishcouncil.org/new/learning/

12.

http://www.cambridge.org/learning/

При подготовке к практическому занятию необходимо использовать рекомендованную литературу и Интернет-ресурсы. При подготовке к пункту 1 следует подробно ознакомиться с речевыми единицами общения (речевая ситуация, речевое событие, речевое взаимодействие). В пункте 2 необходимо ознакомиться с речевыми образцами и лексическими единицами по заданной теме и представить анкету для обучения в России, а также разработать программу профессионального обмена для преподавателей. В пункте 3 студент представляет слайдпрезентацию своей научной работы, используя полученные знания.

26

Приложение 3

Самостоятельная работа по курсу «Иностранный язык в профессиональной коммуникации»

27

При выполнении самостоятельной работы обучающиеся пользуются рекомендуемой основной и дополнительной литературой.

Формы контроля самостоятельной работы: прием перевода научных статей по заданной тематике, реферирование и аннотирование научных статей, написание эссе, подготовка устных сообщений и докладов на английском языке по заданной тематике. Профессиональноориентированные тексты отбираются согласно направлению подготовки и квалификации обучающихся.

Раздел дисциплины: Стратегии устного и письменного перевода.

Тема: Виды и методы перевода.

Задание:

1.

Перевести текст.

2.

Привести примеры конструкции сложного дополнения (Complex Object).

3.

Написать эссе.

При подготовке задания 1 необходимо прочитать текст, обращая внимание на усложненные грамматические структуры, выбрать наиболее походящие стратегии и методы перевода. Подчеркнуть в тексте предложения с конструкцией сложного дополнения.

WHAT IS A HISTORICAL FACT? by E.H.Carr

What is a historical fact? This is a crucial question into which we must look a little more closely. According to the commonsense view, there are certain basic facts which are the same for all historians, and which form, so to speak, the backbone of history — the fact, for example, that the

Battle of Hastings was fought in 1066. But this view calls for two observations. In the first place, it is not with facts like these that the historian is primarily concerned. It is no doubt important to know that the great battle was fought in 1066 and not in 1065 10 or 1067, and that it was fought at Hastings and not at Eastbourne or Brighton.

The historian must not get these things wrong. But when points of this kind are raised, I am reminded of Housman's remark that «accuracy is a duty, not a virtue». To praise a historian for-his accuracy is like praising an architect for using well-seasoned timber or properly mixed concrete in his building. It is a necessary condition of his work, but not his essential function. It is precisely for matters of this kind that the historian is entitled to rely on what have been called the «auxiliary sciences» of history — archaeology, epigraphy, numismatics, chronology, and so forth.

The historian is not required to have the special skills which enable the expert to determine the origin and period of a fragment of pottery or marble, to decipher an obscure inscription, or to make the elaborate astronomical calculations necessary to establish a precise date. These so-called basic facts, which are the same for all historians, commonly belong to the category of the raw materials of the historian rather than of history itself. The second observation is that the necessity to establish these basic facts rests not on any quality in the facts themselves, but on an a priori decision of the historian.

It used to be said that facts speak for themselves. This is, of course, untrue.

The facts speak only when the historian calls on them: it is he who decides to which facts to give the floor, and in what order or context. It was, I think, one of Pirandello's characters who said that a fact is like a sack — it won't stand up till you've put something in it. The only reason why we are interested to know that the battle was fought at Hastings in 1066 is that historians regard it as a major historical event. It is the historian who has decided for his own reasons that Caesar's crossing of that petty stream, the Rubicon, is a fact of history, whereas the crossing of the Rubicon by millions of other people before or since interests nobody at all. The fact that you arrived in this building half an hour ago on foot, or on a bicycle, or in a car, is just as much of a fact about the past as the fact that Caesar crossed the Rubicon. But it will probably be ignored by historians. Professor Talcott Parsons once

28

called science «a selective system of cognitive orientations to reality». It might perhaps have been put more simply. But history is, among other things, that. The historian is necessarily selective. The belief in a hard core of historical facts existing objectively and independently of the interpretation of the historian is a preposterous fallacy, but one which is very hard to eradicate.

The historian starts with a provisional selection of facts, and a provisional interpretation in the light of which that selection has been made — by others as well as by himself. As he works, both the interpretation and the selection and ordering of facts undergo subtle and perhaps partly unconscious changes, through the reciprocal action of one or the other. The historian and the facts of history are necessary to one another. The historian without his facts is rootless and futile; the facts without their historian are dead and meaningless. My first answer therefore to the question «What is history?» is that it is a continuous process of interaction between the historian and his facts, an unending dialogue between the present and the past.

Напишите эссе на тему «What is a historical fact?».

Раздел дисциплины: Аннотирование и реферирование.

Тема: Аннотация. Виды аннотаций.

Задание:

1.

Переведите аннотацию на английский язык (1 на выбор).

2.

Прочитайте текст. Напишите аннотацию к тексту, выделите ключевые слова.

ТРАНС Ф ОРМАЦИЯ АМЕРИКАНСКО Г О КОНСЕРВАТИ З МА

НА РУБЕЖЕ 1980–1990-х ГОДОВ: ДИСКУССИЯ ПО СОЦИАЛЬНО-КУЛЬТУРНЫМ ВОПРОСАМ

В статье исследуется процесс трансформации американского консерватизма в конце 1980-х – начале 1990-х гг. Рассматриваются позиции различных групп и течений консервативного движения

США по социально-культурным вопросам. Делается попытка ответить на вопрос, находится ли консервативное движение в состоянии кризиса или мы можем говорить о новом этапе в его развитии и начале формирования единой социально-политической стратегии.

Ключевые слова: американский консерватизм, республиканская партия, социальная политика, неоконсерваторы.

ОБЩЕСТВЕННЫЙ ТРАНСПОРТ З АПАДНОЙ СИБИРИ В 1930–1950-е ГОДЫ

В статье рассматривается процесс эволюции общественного транспорта Западной Сибири от его зарождения в регионе в годы первых пятилеток до конца 1950-х гг., ставших временем ускоренного развития традиционных для Сибири видов городского сообщения. Особое внимание уделено проблемам транспорта периода Великой Отечественной войны. Автор анализирует динамику развития материально-технической составляющей системы, количественные показатели транспортных услуг, оказываемых населению.

Ключевые слова: общественный транспорт, трамвай, троллейбус, автохозяйство, Западная Сибирь,

Великая Отечественная война.

РОССИЙСКИЙ ТУРИЗМ В1920–70-х ГОДАХ: СИСТЕМА ОРГАНИЗАЦИИ И УПРАВЛЕНИЯ

Возникновение советского туризма относится к началу 20-х гг. ХХ в. После октября 1917 г. в России распались все старые формы организаций в сфере туризма и одновременно начался поиск новых. Вновь создаваемые туристские объединения активно использовали опыт работы дореволюционных.

Изменение задач в политике туризма требовало перестроения структуры управления туристской сферой.

Ключевые слова: туристское движение, туристские организации, структура управления туризмом. слова.

При подготовке вопроса 2 прочитайте текст. Напишите аннотацию к тексту и ключевые

29

SUBSISTENCE ALLOWANCE

A hundred years ago it was a widely accepted belief that no one had responsibility for his neighbour. It was assumed and scientifically «proved» by economists that the laws of society made it necessary to have a vast army of poor and jobless people in order to keep the economy going. Today, hardly anybody would dare to voice this principle any longer. It is generally accepted that nobody should be excluded from the wealth of the nation, either by the laws of nature, or by those of society. The rationalisations which were current a hundred years ago, that the poor owed their condition to their ignorance, lack of responsibility — briefly to their «sins»— are outdated. In all Western industrialized countries a system of insurance has been introduced which guarantees everyone a minimum of subsistence in case of unemployment, sickness and old age. It is only one step further to postulate that, even if these conditions are not present, everyone has the right to receive the means to subsist. Practically speaking, that would mean that every citizen can claim a sum — enough for the minimum of subsistence — even though he is not unemployed, sick or aged. He can demand this sum if he has quit his job voluntarily, if he wants to prepare himself for another type of work, or for any personal reason which prevents him from earning money, without falling under one of the categories of the existing insurance benefits, in short, he can claim this subsistence minimum without having to have any «reason». It should be limited to a definite period of time, let us say two years, so as to avoid the fostering of a neurotic attitude which refuses any kind of social obligations.

This may sound like a fantastic proposal, but so would our insurance system have sounded to people a hundred years ago. The main objection to such a scheme would be that if each person were entitled to receive minimum support, people would not work. This assumption rests on the fallacy of the inherent laziness in human nature; actually, aside from neurotically lazy people, there would be very few who would not want to earn more than the minimum, and would prefer to do nothing rather than work!

However, the suspicions against a system of guaranteed subsistence minimums are not unfounded from the standpoint of those who want to use ownership of capital for the purpose of forcing others to accept the work conditions they offer. If nobody were forced to accept work in order not to starve, work would have to be sufficiently interesting and attractive to induce one to accept it. Freedom of contract is possible only if both parties are free to accept and reject it; in the present capitalist system this is not the case.

But such a system would be not only the beginning of real freedom of contract between employers and employees; it would also enhance tremendously the sphere of freedom of interpersonal relationship between person and person in daily life.

(by Erich Fromm from The Sane Society, 1955)

При подготовке задания необходимо ознакомиться с правилами составления резюме (см.

Приложение «Справочный материал»).

При подготовке текста научного (общекультурного) характера к реферированию, необходимо ознакомиться с основными правилами и требованиями реферирования (см.

Приложение «Справочный материал»). Прочитайте, переведите текст, приготовьте реферирование статьи.

Раздел дисциплины: Резюме. Моя научная работа.

Тема: Резюме. Реферирование.

Задание:

1.

Составьте резюме.

2.

Приготовьте реферирование текста.

30

Challenges to Academic Freedom: Some Empirical Evidence

MICHELE ROSTAN

Academic freedom has been understood as a central feature of the academic profession and as one of its founding values. In the European tradition, academic freedom has been associated both with the freedom to choose topics, concepts, methods and sources both in teaching and research, and with the right of academic staff to make contributions according to standards and rules established by the academic community itself. This view of academic freedom has been complemented in the American tradition by a concern for academics’ civil and political freedom looking at their role in a wider arena than universities and the academic world.

Academic freedom has also been considered as a key condition to achieve several goals: the advancement of knowledge, the quality of research (considered as the main focus of academic work), the encouragement and support of initiative, innovative behaviour, criticism and variety. Academic freedom has also been strictly connected to professional autonomy, as regards academics’ individual freedom to pursue truth without fear of negative sanctions, restrictions, or constraints from religious or political authorities, as well as their freedom to organise their work, to determine research and teaching goals and priorities, to set standards and rules to assess and steer academic activity.

In the last few decades, this view of academic freedom has been challenged. Several ongoing processes within higher education have had an impact on academic freedom.

First, the relationship between the state and higher education has changed. Governments have moved from more direct forms of control towards a system of distant steering that accords more autonomy to higher education institutions but at the same time requires more accountability from single organisations and their professionals (i.e. academics) alike. Several devices of distant steering have been introduced, but they all aim at assessing the performance of both institutions and academics and at establishing a closer link between funding and performance.

Second, there has been a shift in the distribution of power within higher education institutions.

As higher education institutions have become more autonomous corporate bodies, the role of administrative staff has grown at the expense of the academic community. Ever more often academic staff have been confronted with a new kind of more professionalised management. This new type of management provides growing support to tackle an expanded and diversified student body or more complex research activities, but also strengthens control over academic life.

Finally, both higher education institutions and academics have been confronted with the increasing demands and pressures of both the economy and society to support economic development, innovation, and social progress, to provide highly qualified labour force, and to foster graduates’ employability.

Academics are urged to be more responsive to the demands of a wider constellation of actors including not only their peers but students and their families, management, governments and public agencies, and other external stakeholders ranging from private business firms to local communities.

Ever more often academics are asked to prove the relevance or utility of their teaching and research for societal and economic needs; hence, they possibly become less free or less autonomous in setting the ends and the means of their activities.

Pressures for relevance are not new in higher education, and claims for relevance have always been central to academic activity, especially in more applied disciplines. What is new is that: (a) the number and variety of actors to whom academic activities might be relevant have grown; (b) the number and variety of actors who can decide whether claims of relevance are supported by evidence have also increased; (c) pressures on academic staff to prove the relevance of their teaching and research are increasingly associated with the need to find ways to measure it; (d) the number and variety of channels or mechanisms through which growing expectations of relevance intrude into the academic profession have increased.

External expectations of relevance are channelled to individual academics through specific vehicles, such as financial support, evaluation of teaching and research, students’ satisfaction surveys, links between universities and industry (e.g. patent licensing, spin-offs, technology transfer), other

31

links between academe and the economy (e.g. consultancies and universities’ contributions to regional development). It is precisely through these channels or mechanisms that external expectations of social and economic relevance might have an impact on academic freedom in the form of pressures to change or redirect teaching and/or research activities, restrictions on teaching or research activities, external influence on teaching and research, etc.

Data collected through the CAP survey provide information on some of these topics. The survey features three sets of questions, namely those on the evaluation of teaching, on research funding, and on some links connecting academics to the economic sector, which allow us to identify, at the same time, mechanisms through which expectations of social and economic relevance intrude into the academic profession, external actors with whom individual academics are confronted, and possible consequences on academic freedom. In addressing these issues, we have limited data analysis to five European countries – Finland, Germany, Italy, Norway and the United Kingdom – with an occasional reference to Australia and the US as terms of comparison outside Europe. Both cross tabulations and multivariate analysis are used in order to take into account the four main axes of differentiation of the academic profession, namely the discipline, the institutional dividing line, the ranking system, and national differences. While full results of the analysis can be obtained from the author, in the following selected evidence and synthetic conclusions are presented.

European Review, Vol. 18, Supplement no. 1, S71–S88

Academia Europaea 2010.

При подготовке заданий необходимо изучить этикет написания письма, ознакомиться с правилами составления деловых писем на английском языке, а также некоторыми правилами английской пунктуации и орфографии. При подготовке необходимо использовать рекомендованную литературу (Басс, Э.М. Научная и деловая корреспонденция / Ю.М. Басс. –

М.: Наука, 1991. Ступин, Л. П. Письма по-английски на все случаи жизни: учебно-справочное пособие для изучающих английский язык / Л.П. Ступин. — СПб.: Просвещение, 1997).

Обратите внимание на употребление основных клише и фраз, используемых в деловых письмах

(см. Приложение «Справочный материал».)

Раздел дисциплины: Деловая переписка.

Тема: Деловая переписка.

Задание:

1.

Составьте деловое письмо.

2.

Составьте мотивированное письмо.

Раздел дисциплины: Деловое общение по телефону.

Тема: Запрос информации. Оформление и размещение заказа. Решение проблем.

Задание:

1.

Составьте диалог.

Составьте диалог по теме, используя основные речевые клише, фразы (см. Приложение

«Справочный материал»). Обратите особое внимание на такие ключевые моменты, как запрос информации, оформление заказа, решение проблем (см. Приложение «Справочный материал»).

Раздел дисциплины: Международное научное сотрудничество.

Тема: Моя научная работа. Научное сотрудничество.

Задание:

1.

Составьте сообщение о своей научной роботе.

2.

Напишите реферат.

32

3.

Составьте аннотацию к тексту.

Подготовьте сообщение о своей научной работе (тема, цель, задачи, актуальность, объект, предмет и т. п.), научном руководителе, опыте участия в конференциях, научных семинарах и др. Объем сообщения не менее 25-30 предложений. Сообщение может сопровождаться презентацией.

При подготовке заданий 2 и 3 прочитайте текст, определите цель статьи, выпишите ключевые предложения, напишите реферат и аннотацию к статье.

Globalization, Environmental Change, and Social History: An Introduction

Peter Boomgaarda, Marjolein 't Harta

Throughout the ages, the activities of humankind have weighed considerably upon the environment. In turn, changes in that environment have favoured the rise of certain social groups and limited the actions of others. Nevertheless, environmental history has remained a “blind spot” for many social and economic historians. This is to be regretted, as changes in ecosystems have always had quite different consequences for different social groups. Indeed, the various and unequal effects of environmental change often explain the strengths and weaknesses of certain social groups, irrespective of their being defined along lines of class, gender, or ethnicity.

This Special Issue of the International Review of Social History aims to bring together the expertise of social and environmental historians. In the last few decades of the twentieth century, expanding holes in the ozone layer, global warming, and the accelerated pace of the destruction of the tropical forests have resulted in a worldwide recognition of two closely related processes: globalization and environmental change. The contributions to this volume provide striking case studies of such connections in earlier periods, revealing a fruitful interconnection between social and environmental history. This introduction provides a historiographical context for the essays that follow, focusing on the relevant notions connected with globalization and environmental change, and stressing the existing interactions between environmental and social history. We are particularly interested in the consequences of processes induced by globalization, how transnational forces and agents changed the socio-ecological space, and how that affected relationships between different classes in history.

Globalization And Global History

Globalization is a concept that needs further elaboration. The rise of the internet, the shifts in the power of sovereign national states, the intricate intertwining of global markets, and the enormous numbers of people migrating across regions and continents trying to escape wars, environmental degradation, or disasters have prompted several scholars to explain these recent trends using new definitions of globalization. The description by the political scientists David Held and Anthony

McGrew nicely captures our understanding: