Annual Reports

advertisement

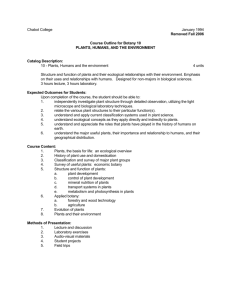

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Archival Materials Archival sources were essential to understanding the Glass Flowers exhibit. The Botanical Museum Records of Harvard, donated by the Glass Flowers patrons Elizabeth C. Lee and Mary Lee Ware, provided irreplaceable evidence regarding the profound artistic and educational value that the exhibit had from its outset. Because the collection is limited to what the Wares received and kept, many direct details of the Wares’ involvement and opinions remained hidden to me. Nevertheless, the collection possesses a wealth of sources, including photographs, slides, correspondences, which I used to discuss Goodale’s purpose in commissioning the Ware Collection and to conceptualize the internal debates in the development of the Ware Collection. The bulk of the letters were sent to the Wares from Goodale and from the Blaschkas. For the convenience of researchers, the letters most closely oriented toward the Glass Flowers commission have been copied and separated from the original boxes. The Walter Deane Papers were invaluable in telling me the perspective of Rudolph Blaschka, whose letters to Deane are preserved here; a close friend to Deane, Rudolph was candid about his work and employed Deane to collect grass specimens for one of the later Glass Flower series. The Administrative Correspondence of the Gray Herbarium and the Papers of William Gilson Farlow revealed the politics within Harvard’s Botany Department and the conflicts between Goodale and his colleagues. The George Lincoln Goodale Miscellany folder in the Administrative Correspondence of the Gray Herbarium includes short notes from Goodale to the librarian at Gray Herbarium, as well as several letters from Goodale to Benjamin Robinson, Alexander Agassiz, and others. The Farlow Papers demonstrate, in many instances, Farlow’s disdain for Goodale. While obtaining primary sources on the Wares was difficult, I eventually encountered the Mary Lee Papers in Schlesinger Library. The collection contains a series of correspondences between the young Mary Lee, Mary Ware’s cousin, and Elizabeth C. Ware—referred to as Aunt Lizzie. I obtained other general information on women in botany in The Papers of Mary Ernst Archibald, which contained one of her examinations from Goodale’s elementary botany class, and The Records of Radcliffe Council, which contained one correspondence with Goodale. The papers of George Lincoln Goodale in the Harvard Archives are unfortunately few, limited to later correspondences and a series of diaries 1910-1921, written mostly in French. From what I could read in Goodale’s diaries, I found an initial glimpse into his interests and his Humboldtian approach to describing daily weather conditions, but ultimately could not use the diaries. The diaries of Henrietta Jewell Goodale were similarly interesting, and provided excellent travel narratives of the Goodales’ trips to Europe. One of the diaries 1900-1901 contains the only available description of the Blaschka studio, and bits of Henrietta’s writing gave me glimpses into the lives of her husband George and Mary Lee Ware. Harvard University Archives Accession 14253 is a newly-available collection of photographs from the Glass Flowers exhibit, taken in 1931 by a photographer named Dadman. The photographs are beautiful, and I included two of them in my final thesis. 105 Administrative Correspondence Files. Gray Herbarium Library. Harvard University Herbaria. Papers of George Lincoln Goodale. Harvard University Archives. Cambridge. 18851921. 3 boxes. Henrietta Jewell Goodale Diaries. Schlesinger Library. Radcliffe Institute. Harvard University. 1881-1882, 1899-1915. Papers of Mary Ernst Archibald, Class of 1903. Radcliffe College Student Life and Activities Collection. Radcliffe College Archives. Botanical Museum Records, Harvard University. Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants. ca. 17 linear feet. Mary Lee Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Cambridge.Walter Deane Papers, 1881-1929, Archives, Gray Herbarium, Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge. Records of the Radcliffe Council. RG I, series 2, folder B5. Radcliffe College Governing Boards Records, Radcliffe College Archives, Schlesinger Library, Cambridge. Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants. Harvard University Archives Accession 14253, 1931. William Gilson Farlow Papers, Farlow Reference Library, Harvard University, Cambridge. 1880-1899. Writings of George Lincoln Goodale The Glass Flowers exhibit, a testament to public education through artistically appealing objects, best states Goodale’s contributions. Indeed, he focused more on his work as an administrator and a lecturer than on aiming to produce a voluminous set of works as his predecessors and colleagues did. In his Address at the Dedication of the Mary Francis Searles Science Building, Goodale argued that scientific education should feature both laboratory observation and “dogmatic” information on the practical applications of that science. “Asa Gray” was one of the myriad articles written in Gray’s memory, detailing his life, works, and religious leanings. To develop his Botanical Museum, Goodale visited Ceylon, Australia, and other countries in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific, assessing the usefulness of colonial botanical gardens and museums in his article series, “Botanic Gardens in the Equatorial Belt and in the South Seas.” Goodale’s catalogue of flowering plants in Maine, where he taught at Bowdoin College, demonstrates his initial interests in taxonomy that enabled 106 him to begin correspondence with Gray. Concerning a few common plants similarly illustrates Goodale’s understanding of taxonomy. Because of Goodale’s interests in economic and physiological botany, I looked at his Physiological Botany volume from Gray’s Botanical Textbook. This volume was the first physiological botany textbook available in America. Goodale’s interests in educating his public are evidenced by A Course of Lectures on Forests and ForestProducts and Suggestions for Science-Teaching in Secondary Schools. The latter selection made a strong argument: that educators should encourage inquisitiveness in children, and that scientific methods taught children the values of singleness of purpose, directness of aim, and truthfulness. “The Development of Botany as shown in this Journal” traced the history of botany as represented in the journal Science, and Goodale took special care to illustrate Asa Gray’s unique interpretation of Darwin. I used the collection of Goodale’s writing to illustrate Goodale’s strong interests in applying Darwinian science to the practical world, especially illustrated in “The Influence of Darwin on the Natural Sciences,” and his desire to educate the public as a method of advancing botany. These writings effectively complement Goodale’s letters. Goodale, George Lincoln. Address at the Dedication of the Mary Frances Searles Science Building, Bowdoin College, September 28, 1894. Lewiston: Printed at Journal Office, 1894. ———. “Asa Gray.” Nation (Feb. 2, 1888). ———. “Botanic Gardens in the Equatorial Belt and in the South Seas.” American Journal of Science 42 (1891) 173-177, 260-264, 348-352, 435-438, 517-522. Title varies. ———. A Catalogue of the Flowering Plants of Maine. Portland: 1862. ———. Concerning a Few Common Plants. 2nd ed. Guides for Science-Teaching, No. 2. Boston: Boston Society of Natural History, 1879. ———. A Course of Lectures on Forests and Forest-Products. Boston: Lowell Institute, Feb. and Mar. 1888. ———. “The Development of Botany as Shown in This Journal.” American Journal of Science 46 (1918): 399-416. ———. “The Influence of Darwin on the Natural Sciences.” The Darwin Centenary (April 23, 1909): 1-10. ———. Physiological Botany. Vol. 2. Gray’s Botanical Text-Book. New York: Ivison, 1885. ———. “Some of the Possibilities of Economic Botany.” The American Journal of Science XLII (Oct., 1891): 271-303. 107 ———. A Suggestion for Science-Teaching in Secondary Schools. Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1890. Annual Reports Consulting the Botanic Garden and Botanic Museum sections of the Annual Reports of Harvard College was essential to my research. Harvard’s Annual Reports showed the goals of Goodale and his colleagues for the development of their departments, and provided an excellent timeline for the sequence of changes in the Glass Flowers exhibit. The contents of the Annual Reports for both schools are available online at http://hul.harvard.edu/huarc/refshelf/HROHRSHome.htm. The Harvard Treasurer’s Reports provided names of donors to the Botanical Museum fund in its early years. The Radcliffe Annual Reports formed an important lens for me into the history of woman and botany in a collegiate environment. The reports demonstrated the levels of enrollment in the botany department as well as Goodale’s efforts to increase funding and support for the women’s botany program. The Annual Reports of the American Museum of Natural History helped provide me with the interests and goals of one of Harvard’s sister natural history museums. American Museum of Natural History. Annual Report, 1870, 1882, 1883, 1887. Harvard University, Annual Reports. 1834-1929. From 1834 to 1869, these were called the Annual report of the President of Harvard University to the Overseers on the state of the university for the academic year … From 1869 to 1877, the President’s Reports retained the same title but reports of the Botanic Garden appeared in their own section. The Reports were called Reports of the President and the Treasurer of Harvard College 1878 to 1929. After 1909 the Botanical Museum and the Botanic Garden appeared in different sections of the annual report. Harvard University. Treasurer’s Statement. 1885-1891. Radcliffe College, Annual Reports. 1880-1900. In 1880 the report was called Courses of study for 1880-81 with requisitions for admission and report of the first year. 1881-1882 the title was Reports of the Treasurer and Secretary (Private Collegiate Instruction for Women in Cambridge, Mass.), and 1883-1893, Reports of the Treasurer and Secretary (Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women). The rest of the titles were: in 1894, Reports of the president, regent, and treasurer, 1895, Reports of the president, dean, regent, and treasurer, and 18961912 Annual reports of the president and treasurer of Radcliffe College. 108 Publications on the Glass Flowers Each of these articles, in a different way, illustrates the story of the glass flowers and the various issues implicit in its creation. I did not divide the articles into primary and secondary sources, because several of the articles worked as both. They were generally informative, but some very clearly illustrated artistic appreciation of natural history at the time when the glass flowers exhibit was being created, as well as the increasingly legendary quality that the Ware Collection grew to possess. Instead, I divided the collection into three categories and used the articles in my thesis that came after 1990 as secondary sources. It would be repetitive and unnecessary for me to repeat the contents of the various publications in the following list. The internal publications succeed in romanticizing the glass flowers in addition to providing detailed information about them, whereas the various articles written 1893-1839 present various narratives about the exhibit, and explain the values of the exhibit to the public as educational devices, objects for edification, and examples of innovative glass working. Many of the selections were taken from the Botanical Museum Records, which holds an archive of articles (1893present) along with a Glass Flower Bibliography (1878-1998). I have included further explanations below article listings where the articles have provided new or notable interpretations of the Glass Flowers. Internal Pamphlets and Books: The majority of these publications are guidebooks to the flowers. Ames, Oakes. The Ware Collection of Glass Flowers in the Botanical Museum of Harvard University. Cambridge: Botanical Museum, Harvard University, 1963. Botanical Museum of Harvard University. “The Ware Collection of Blaschka GlassModels of Plants.” 1911. Botanical Museum of Harvard University. “The Ware Collection of Blaschka GlassModels of Plants in Flower.” 1915, 1916. “de Huarte, Mrs. “Another “here’s to”…” ca. 1957-58. Botanical Museum Records. Harvard University. Cambridge. This is a humorous poem about the Botanical Museum, written by one of its staff member. Botanical Museum of Harvard University. The Ware Collection of Blaschka GlassModels of Plants in Flower. Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1916. Kredel, Fritz, Oakes Ames, Albert F. Hill. Leopold Blaschka, and Rudolph Blaschka. Glass Flowers from the Ware Collection in the Botanical Museum of Harvard University Insect Pollination Series. New York: Harcourt, 1940. Schultes, Richard Evans and William A. Davis. The Glass Flowers at Harvard. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1982. 109 Ware, Mary Lee. “How Were the Glass Flowers Made?” Botanical Museum Leaflets 19. Harvard University, 1961. This pamphlet is a published letter from Miss Ware to Oakes Ames in 1928, in which Mary gives a detailed account of the making of the Blaschka exhibit. Her narrative of Rudolph Blaschka and his work is especially poignant. Wiley, Franklin Baldwin. Flowers That Never Fade: An Account of the Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models in the Harvard University Museum. rev. from Boston Transcript, 1893. Boston: Bradlee Whidden, 1897. Contains the first poem written about the Glass Flowers. Articles and References to the Glass Flowers: 1893-1939: the following articles appeared in local and national publications before the death of Rudolph Blaschka. “The Blaschka Glass Models in the Harvard University Museum.” Harvard Summer School Bulletin 1, no. 3, 22 July 1901. “Blaschka’s Retirement Marks ‘Glass Flower’ Collection End.” Christian Science Monitor, 6 December 1937, 9-11. Discusses Blaschkas’ artistic accuracy. Cary, Emma. “A Garden of Glass.” The Young Catholic, 20 January 1895, 23-24. Contains reference to glass flowers and religion. Deane, Walter. “The Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Flowers at Harvard.” Botanical Gazette 19, no. 4 (18 April 1894): 144-148. Deane’s famous microscopic analysis of the collection. “Designer Ill, Harvard Glass Garden Halted.” Boston American, 5 December 1937. “A Distinguished Visitor: Interview with Professor Goodale.” The Press (Christchurch), 16 January 1891. Flint, Weston B. “Harvard at the World’s Fair.” The Harvard Illustrated Magazine 6, no. 4, October 1904, 6. This article briefly mentions the Glass Flowers among other displays at Harvard’s display at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. “Flowers in Glass Main Spectacle.” Boston Post, 3 October 1938. This article announced that the Ware Collection tops Boston tourists’ destinations. “Flowers Lure Writer Here.” Boston Evening American, 9 July 1936. “Flowers of Glass.” The Pioneer, Electro Bleaching Gas Co. and Niagara Alkali Company (June 1938): 6. “Flowers that Fade Not.” Boston Evening Transcript. (1 May 1893). 110 “Glass Flowers at Harvard.” The Boston Sunday Globe (21 May 1905). “Glass Flowers Attain Final Form as Eyes Fail German Creator Blaschka.” Harvard Crimson, 6 December 1937. “Glass Flowers.” China, Glass, and Lamps, 7 February 1894, 20- 21. “Glass Grasses - Now for the Harvard Museum.” Boston Evening Transcript, 14 February 1922. Goodale, George Lincoln, “The Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants and Flowers in the Botanical Museum of Harvard University.” American Journal of Science (March 1895): 242. Grossman, Max. “The Amazing Human Drama behind New Glass Flowers at Harvard.” Boston Post, 6 November 1932, A-1, A-7. This newspaper article romantically reconstructs the thoughts of Leopold Blaschka, and treats the Glass Flowers as a monopolistic acquisition. “Harvard Adds Glass Flower Exhibits with new Shipment to Agassiz Museum.” Christian Science Monitor, 21 November 1932. “The Harvard University Collection Of Glass Flowers.” Science 36 (17 December 1937): 555. Haven, Charles P. “Ware Family, Glass Flower Patrons, Gave President to Harvard.” Boston Sunday Post, 17 January 1937. Written after the death of Mary Lee Ware, this article discusses the connections of the Ware family to the Glass Flowers. Levitt, W.T. “Modern Aladdins.” Bulletin of the American Ceramic Society 13, no. 11 (November, 1934). “Maker of Flowers of Glass Dead.” Boston Post, 3 May 1939. “Miracles of Glass.” The Glass Container 5 (November 1925): 5-7, 28. Nichols, Herbert. “Harvard’s Glass-ified Garden.” Christian Science Monitor, 16 September 1936, 10-11, 17. An excellent, detailed discussion of the Glass Flowers exhibit. “No More Glass Flowers.” Boston Herald, 4 May 1939. “No More Glass Flowers Made.” Boston Sunday Post, 5 December 1937. 111 Peattie, Donald Culross. Flowering Earth (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1939): 10-11. A botanist discusses how seeing the glass flowers rejuvenated his love for botany. Roorbach, Anne. “Harvard’s Glass Flowers.” American German Review, June 1937, 1417. “The Story of the Glass Flowers.” Harvard Summer School News, 12 July 1935. “Secret Art to Die as Man Goes Blind Who Made Harvard Glass Flowers.” Boston Sunday Herald, 5 December 1937. “Secret of Harvard Glass Flowers Dies with Maker, 82, in Germany.” Boston Herald, 3 May 1939. Simms, Marion. “Harvard’s Flowers of Glass.” Young People’s Weekly (Elgin, Illinois), 29 Jan. 1939, 13. “There Will Be No More Harvard Glass Flowers.” Boston Sunday Globe. 7 May 1939, 2. Van Marter Beede, Vincent. “Miracles in Glass.” House Beautiful, September 1904, 1617. “University Museum to Show New Glass Plants.” Harvard Crimson, 31 October 1932. “The Ware Collection of Glass Flowers.” Harvard Alumni Bulletin (8 March 1928): 681684. Wilkinson, Richard Hill. “Glass Flowers (Short Story).” Boston Herald, 8 March 1934. Amusing fictional tale of the Blaschka-Goodale meeting. Wisehart, M.K. “That Magic Stuff Called Glass.” The American Magazine, July circa 1924, 38-39, 179-181. An article on glass working in which the author marvels at photographs of the Glass Flowers. Yordan, E.L. “Harvard’s Unique Glass Flowers.” New York Times Magazine, 7 February 1937. Books, Articles, and References to the Glass Flowers, Post-1939 Bergin, Dorothy. “Glass Flowers.” Youth Instructor (Seventh-Day Adventists), 2 September 1941, 7-8. Bogan, Louise. “Animal, Vegetable and Mineral.” New Republic, 9 December 1940, 804. 112 Bogan, Louise. “Animal, Vegetable and Mineral.” Collected Poems 1923-53. New York: Noonday Press, 1954: 100. Bogan presents a detailed and puzzling poem about the glass flowers. Brown, Nancy Marie. “Flowers out of Glass.” Research/Penn State 20, no. 3 (1999): http://www.rps.psu.edu/sep99/glass.html. Well-researched and accurate article on the history of the glass flowers and their composition. Fields, Lisa. “A Reverence for Glass.” Horticulture 5, no. 12 (December 1979): 24-29. Flaherty, Julia. “Arts in America: Even Glass Flowers Need to Be Rejuvenated.” The New York Times, 22 August 2001, 2. Hildebrand, J.R. “Glass Goes to Town.” National Geographic Magazine, January 1943, 1-40. Article on glassmaking techniques; one page features a photo of a small glass bouquet that the Blaschkas made for the Wares. Homer, William F. “Harvard Glass Flower Collection puts Modern Craftsmen in Shade.” Boston Herald, 20 May 1947. Enjoyable narrative of glass flowers that discusses the collection in its similarities to old jewelry display cases. Lindsten, Clarence S. “Harvard’s Fabulous Glass Flowers.” American Orchid Society Bulletin (August 1971): 688-90. Minott, Henry. “Glass Flowers Still Outdraw Football.” Boston Globe, 12 March 1954. Nichols, Herbert B. “They Certainly Look Real.” Christian Science Monitor, 12 March 1949. This article describes in detail the relevance of the glass flowers to both aesthetic appreciation of innovation and academia. Pantano, Carlo G., Susan M. Rossi-Wilcox, and David Lange. “The Glass Flowers.” The Prehistory & History of Glassmaking Technology 8 (1998): 61-78. Parke, Margaret. “The Glass Flowers.” American Horticulture 62, no. 12 (December 1983): 22-27. Rossi-Wilcox, Susan Marie, Hillel Burger, and Harvard University Botanical Museum. The Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants: 12 Ready-to-Mail FullColor Postcards of Models on Permanent Exhibit at the Botanical Museum of Harvard University. Cambridge: President and Fellows of Harvard College, 1991. Schultes, Richard Evans, and William A. Davis. “Glass Flowers Bloom Forever in Unique Harvard Collection.” Smithsonian (October 1982), 100-107. 113 Simms, Marion. “Harvard’s Unusual Glass Flowers.” The Gateway (publication of the Presbyterian Church), 5 January 1946: 6-7. Walker, Robert Sparks. “Harvard’s Everlasting Glass Flowers.” Flower and Feather (Chattanooga Audubon Society), 26 September 1956, 49-51. WNAC-TV Boston, Yankee Goes Calling at The Botanical Museum, Harvard University, 22 February 1954. Wright, Karen. “Splendor in Glass.” Discover 2001, http://www.discover.com/jan_01/featworks.html. Botanical Textbooks and Reference Books Reading botany textbooks proved essential for learning the types of education that laypeople and visitors to Harvard’s Glass Flowers exhibit received in the nineteenth century. Beck’s Botany used natural classification and argued that students should not study exotic plants because of the high expense in obtaining specimens. Bessey also used natural classification, and believed that the similarity of design among plants showed that they exhibited a genetic relationship. Asa Gray wrote multiple volumes on botany— including Structural Botany, The Elements of Botany, How Plants Grow, How Plants Behave, The Botanical Textbook, and others. In these works, he focused on the morphology and anatomy of plants, argued that children could achieve sound educations by studying botany, and treated botany as a system of knowledge in addition to a science that fostered moral improvement. Hooker’s Botany showed that botanical study could have purposes in everyday life. Rousseau’s The Reverie of a Silent Walker, an edited edition including his “Letters on Elementary Botany,” played a key role in eighteenth and nineteenth-century culture, defining the roles of women in botany. Ladies’ Botany, by John Lindley, was a very popular botany textbook in the nineteenth century, and it taught natural classification as a way of personal and moral improvement for women. Jane Webb Loudon’s selections showed groupings of commonly cultivated wild flowers and demonstrated Loudon’s hesitation about Linnaean system, and taught women how to garden properly. Almira Hart Lincoln Phelps’s works, The Fireside Friend and Familiar Lectures in Botany, advocated Linnaean botany for the purposes of edification, health, and moral improvement. Redoute’s Les Liliacees was the authoritative book of plant illustrations in the nineteenth century, and reveals the best type of work available in botanical drawings. This source helped me get a perspective on the types of botany drawings people expected to see. Torrey and Gray’s Flora of North America was the first compendium of all taxa found in North America, revealing hints of American naturalism and the desire within the country to form a national identity with the assistance of the nation’s flora. These various textbooks assisted me in discovering the types of arguments and goals that guided botany education in the nineteenth century. 114 Baker, John Gilbert. “Monograph of British Roses.” Linnaean Society Journal 11 (1871): 197-243. Beck, Lewis. Botany of the Northern and Middle States. Albany: Webster and Skinners, 1853. Bessey, Charles E. Botany: For High Schools and Colleges. American Science Series; 5. New York: H. Holt and Co., 1880. Gray, Asa. The Botanical Text-Book. New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1842. ———. Botany for Young People and Common Schools: How Plants Grow, a Simple Introduction to Structural Botany: With a Popular Flora, or an Arrangement and Description of Common Plants, Both Wild and Cultivated: Illustrated by 500 Wood Engravings. New York: Ivison, 1858. ———. Botany for Young People Part II: How Plants Behave: How they Move, Climb, and Employ Insects to Work for them. New York: Ivison, Blakeman, Taylor, and Co., 1872. ———. Elements of Botany. New York: G. & C. Carvill, 1836. ———. Structural Botany: Or Organography on the Basis of Morphology; to Which Is Added the Principles of Taxonomy and Phytography, and a Glossary of Botanical Terms. 6th ed. Vol. 1. Gray’s Botanical Text-book. New York: Ivison, 1880. Hooker, Sir Joseph Dalton. Botany. Science Primers 8. London: Macmillan, 1876. Lincoln Phelps, Almira Hart. Familiar Lectures on Botany, Practical, Elementary and Physiological. rev. and enlarg. ed. New York: Huntington and Savage, 1851. ———. The Fireside Friend. Boston: Marsh, Caben, Lyon, and Webb, 1840. Lindley, John. Ladies’ Botany. 6th ed. 2 vols. London: 1865. Loudon, Jane Webb. British Wild Flowers. 2d ed. London, 1847. ———. Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden. 2d American, from the 3d London. A. J. Downing. ed. New York: Wiley, 1863. Redoute, Pierre Joseph. Les Liliacees. 8 vols. Paris: 1802-1816. Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, The Reveries of the Solitary Walker. ed. Christopher Kelly. trans. Charles E. Butterworth et al. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2000. 115 Torrey, John and Asa Gray. A Flora of North America. New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1838-1840. Primary Sources regarding Women and Botany, non-textbook forms Harper’s Weekly and the Ladies Floral Cabinet and Home Companion served as well-springs of information on women’s attitudes towards botany and how they experienced natural history in their daily lives. Adams’s brief article revealed how, by the end of the nineteenth century, botany was established firmly a subject especially for women, and that most men seemingly required convincing to believe that they should participate in botany. The manuals Wax Flowers; How to Make Them and The Artifical Florist demonstrate what issues were important to persons interested in creating wax flowers as a hobby, and I used them to illustrate women’s tradition of wax flower making. Van Kleeck’s volume demonstrates the women’s industry of artificial flower making in the early twentieth century. Archduke Joseph’s catalog of medicinal plants was created in dedication to a priest who helped Archduke Joseph during a time of severe illness (his treatments included water cure and plant therapies). The Archduke’s daughter, Baroness Margarethe, painted the images in the book; her artistic participation in this venture was typical of young women interested in botany. J. F. A. Adams, M.D. “Is Botany a Suitable Study for Young Men?” Science 9 (1887): 117-118. Joseph, Archduke of Austria. Atlas Der Heilpflanzen Des Praelaten Kneipp. Regensburg: Verlag von W. Wunderling’s Hofbuchhandhung, 1903. Foster, John. The Artificial Florist; or, the Art of Making Artificial Flowers. Easy Progressive Lessons. London: Published by the Author, 1838. Harper’s Weekly. Greenwich, Connecticut, 1857-1912. Database online. Available through HarpWeek. The Ladies’ Floral Cabinet and Home Companion. New York: H.T. Williams, 18741875. Available on Microform. Van Kleeck, Mary. Artificial Flower Makers. New York: Survey Associates, Inc., 1913. Wax Flowers; How to Make Them. Boston: J.E. Tilton, 1864. 116 Miscellaneous Primary Sources Josselyn, John, and Edward Tuckerman. New-England’s Rarities Discovered in Birds, Beasts, Fishes, Serpents, and Plants of That Country. Boston: W. Veazie, 1865. John Josselyn’s book was a good introductory source to materia medica in the colonies, and I used it to introduce the study of systematics. New England Botanical Club. Constitution of the New England Botanical Club, with a List of the Officers and Members of the Club. Boston: The Club, 1898-1929. This set of books helped me to conceptualize the key botanists in Boston, shown in this all-male botanical society. Goodale was President of the Club for two years, and remained a member until his death. Secondary Works Biographies and Published Correspondences The various biographies I consulted were of immense use in helping me put events surrounding the Glass Flowers into context. Both Lurie and Dupree’s biographies provided excellent, authoritative looks at Harvard scientists Asa Gray and Louis Agassiz. Deane and Riley’s articles provided excellent memorials to Gray’s life and unique perspectives on Gray as an educator and as a supporter of Darwin. Letters of Asa Gray helped me to discern issues important to Gray and showed his various roles at Harvard. Emily Hale’s memorial to her lifelong friend Mary Lee Ware included a brief excerpt on Miss Ware’s presence as a botanist and her love for the glass flowers. Although Robert Tracy Jackson and Benjamin Robinson’s brief biographies of George Lincoln Goodale provide excellent memorials for him, Harvard’s history still lacks a good discussion of Goodale, who exhibited a profound exhibit on Harvard’s relationship in educating the public through his Botanical Museum. Nonetheless, I found the available biographies useful in understanding the ways in which Goodale’s colleagues remembered him. Robinson’s biography, especially, presented Goodale’s desire to educate the public and interests in economic and physiological botany very effectively. Deane, Walter. “Asa Gray.” Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club (March 1888): 59-72. Dupree, A. Hunter. Asa Gray, 1810-1888. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1959. Gray, Asa, and Jane Lathrop Loring ed. Letters of Asa Gray. 2 vols. Boston and New York: Houghton, 1893. Hale, Emily. Mary Ware. Boston: 1937. 117 Jackson, Robert Tracy. “George Lincoln Goodale.” Harvard Graduates’ Magazine, September 1923, 54-59. Lurie, Edward. Louis Agassiz: A Life in Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960. C.V. Riley, “Personal Reminiscences of Dr. Asa Gray,” Botanical Gazette 13 (July, 1888), 178-186. Robinson, Benjamin Lincoln. Biographical Memoir, George Lincoln Goodale, 18391923. Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences, V. 21, 6th Memoir. Washington: U. S. Govt. Print. Office, 1926. This detailed memoir traces Professor George Lincoln Goodale’s life and provides explanations for his decisions as director of Harvard’s botanical museum. History and Theories of Museums of Natural History I consulted a variety of secondary sources to learn about the factors involved in the creation of museums. Edward Alexander’s works argued that curators had a profound impact on the course of the making of museums and imposed their values on their public displays. According to O’Malley, botanic gardens became a quintessential part of garden art and scientific inquiry, and that they proved useful in fostering American nationalism. Conn argued that museums emerged definitively out of American intellectual advancement in the Victorian age, but that this trend ended as new exhibits were formed to appeal directly to the public. Kohlstedt’s “Essay Review” pointed out that few museum histories have been written discussing intellectual changes and influence of the public, and she lauded the work Mary Winsor and Ronald Rainger. Mary Winsor provided some of the most directly relevant analysis to my study of the Glass Flowers exhibit. Reading the Shape of Nature, which detailed the formation of Agassiz’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, effectively discussed the nature of Agassiz’s exhibits and their support of creationism. Winsor ultimately treated her study as a gaze into the process of collecting and how objects acquire meaning by being placed in museum exhibits. Her other selection, Jellyfish, Starfish, and the Order of Life, gave an excellent history of classification and what systems meant to the study of biology. Orosz looked at the development of museums between 1740 and 1870, arguing that the development of museums at this time allowed them to become centers of popular education and scholarly research. Kohlstedt’s essay in Rainger’s The Development of American Biology took up an examination of museums where Orosz ended, examining the role of museums as centers of intellectual development and public education. Susan Sheets-Pyenson looked at public exhibits versus research-oriented exhibits, tracing how colonial exhibits came into their own to contain a wealth of scientific information from foreign countries, peaking in 1900. Yanni’s Nature’s Museums looked at the cultural environment that shaped museum architecture, and how these people’s values influenced displays in both natural history and art museums. Neil Harris related museum culture and organization to techniques of marketing scientific education to the public, and I used his 118 book to demonstrate the perceived relationships between museums, World’s Fairs, and department stores within consumer culture. Collins and Goode’s works are listed as secondary sources, but because they were written originally in the late nineteenth century, they both exhibit theories and ideologies of museum-making that were immediately accessible, and considered, by Goodale and his colleagues. As Curator of the Smithsonian Institution, Goode played a great part himself in the creation of nineteenth-century museums. Collins provided a colonialist’s perspective on the formation of museums, and I used it to demonstrate how people of his time believed women could contribute best to botanical museums. Less useful was Stephen Asma’s Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads. Although Asma gave interesting perspectives on how philosophical changes in science affected museum exhibitions, the ways in which he used his sources were unclear because his work lacked citations. Alexander, Edward P. The Museum in America: Innovators and Pioneers. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 1997. ———. Museum Masters: Their Museums and Their Influence. Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1983. Asma, Stephen T. Stuffed Animals & Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. Collins, J. Franklin B. “Occasional Papers. Museums: Their Commercial and Scientific Uses, 1875.” The Journal of Eastern Asia VI (July 1875): 5-25. Conn, Steven. Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876-1926. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998. Goode, G. Brown, and Sally Gregory Kohlstedt. The Origins of Natural Science in America: The Essays of George Brown Goode. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991. Harris, Neil. Cultural Excursions: Marketing Appetites and Cultural Tastes in Modern America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990. Kohlstedt, Sally Gregory. “Essay Review: Museums: Revisiting Sites in the History of the Natural Sciences,” Journal of the History of Biology 28 (1995): 151-166. O’Malley, Therese. “Your Garden Must Be a Museum to You: Early American Botanic Gardens,” Art and Science in America: Issues of Representation. ed. Amy Meyers et al. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1998: 39-59. Orosz, Joel J. Curators and Culture: The Museum Movement in America, 1740- 1870, History of American Science and Technology Series. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990. 119 Rainger, Ronald, et al. The American Development of Biology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988. Sheets-Pyenson, Susan. Cathedrals of Science: The Development of Colonial Natural History Museums During the Late Nineteenth Century. Kingston: McGillQueen’s University Press, 1988. ———. “Civilizing by Nature’s Example: The Development of Colonial Museums of Natural History, 1850-1900.” Scientific Colonialism: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. ed. Nathan Reingold and Marc Rothenberg. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987. Winsor, Mary P. Starfish, Jellyfish, and the Order of Life: Issues in Nineteenth-Century Science, Yale Studies in the History of Science and Medicine; 10. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976. ———. Reading the Shape of Nature: Comparative Zoology at the Agassiz Museum, Science and Its Conceptual Foundations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. Yanni, Carla. Nature’s Museums: Victorian Science and the Architecture of Display. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. History of Botany and Natural History I used several secondary sources to acquire background on the history of botanical science. David Allen’s The Naturalist in Britain is a compelling look into British naturalism and I used it to express the difference between Darwin’s role and the roles of other naturalists of his time. Allen also contributed an excellent essay to Nicholas Jardin’s volume Cultures of Natural History: “Tastes and Crazes” traced the role of the Victorian fern craze on nineteenth century culture. Morton’s volume gave me an overview of the history of botany, and I used it to define some key terms in the exhibit. Ewan and Arnold, Humphrey, and Rodgers provided histories of the changes in American Botany after the seventeenth century, and helped me learn about Gray and his colleagues. Stuckey’s collection of essays on botany gave several articles on the history of botany that were written at the end of the nineteenth century. Paul Farber’s Finding Order in Nature gave a general history of naturalism, looking at the discipline as a way of understanding order in the world and defining the oral implications of that order. Scott Atran’s work is fundamental to considering knowledge of the natural order in nineteenth-century culture; he argues that systems of belief in the order of nature derived from common sense notions, giving basis to the fusion between popular culture and the intellectual development of botany. My key source on the history of amateur botany was Elizabeth Keeney’s The Botanizers, which provided an excellent explication of botany for amateurs in nineteenthcentury America, as well as an excellent bibliography. Her volume is the best source 120 available in studying this topic, and it includes sound arguments about the changes in botany education over the century. Jardine’s Cultures of Natural History introduced me to several authors who study various trends in natural history, including Atran, Anne Secord, and Allen. Anne Secord’s essay “Science in the Pub” showed how the work of artisan botanists in the nineteenth century allowed them to create a connection between popular and elite culture. She established the division between popular science and elite science as a social construct created by who could participate in science, and under what terms. Koerner and Stafleu’s texts both gave me good introductions to Linnaeus and helped me to clarify the scope of his theories and the work of his peers. Stafleu looked at Linnaeus in relation to his supporters and opponents. Koerner provided a new look at Linnaeus’s theories in relation to his viewpoints on economics, and she traced how he believed that Sweden could compensate for not having a colonial empire by diversifying plants and animals locally. I used both of these sources to clarify the meanings and implications of Linnaean botany, especially in relation to amateurs. Saunders’s Picturing Plants provided a sound introduction to the history of botanical illustration and the types of illustrations created, though I did not use it in my final thesis. I found it interesting to learn that while most artists drew idealized specimens, some were willing to draw accurate specimens, with imperfections. Overfield’s Science with Practice tells the life of Charles Bessey, who contributed to the rise of New Botany in American Universities; I used this book to characterize the transition between Old and New Botany. Christopher Kirchoff’s thesis, which tells the story of the rise and fall of the Hall of Man in Africa exhibit at the A.M.N.H. provided me with an excellent bibliography on the history of museums. Moore’s volume formed some of my background on the connection between evolutionary theory and religious belief. Moore told of various followers of Darwin, and how they reinterpreted his theory in order to remain consistent with their religious beliefs. Allen, David. The Naturalist in Britain. London: Allen Lane, 1976. Atran, Scott. Cognitive Foundations of Natural History: Towards an Anthropology of Science. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990. Ewan, Joseph Andorfer, and Chester A. Arnold. A Short History of Botany in the United States. New York: Hafner Publishing Company, 1969. Farber, Paul Lawrence. Finding Order in Nature: The Naturalist Tradition from Linnaeus to E.O. Wilson. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000. Humphrey, James Ellis.” Botany and Botanists in New England.” New England Magazine 14 (Boston, 1896), 27-45. Jardine, Nicholas, James A. Secord, and E. C. Spary. Cultures of Natural History. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. 121 Keeney, Elizabeth. The Botanizers: Amateur Scientists in Nineteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992. Kirchhoff, Christopher. From Man in Africa to Africa Peoples Hall: An Exhibit’s Trajectory through the Changing Mores of Science and Society, 1968-2001. Undergraduate Thesis, Harvard University, 2001. Koerner, Lisbet. Linnaeus: Nature and Nation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999. Moore, James R. The Post-Darwinian Controversies: A Study of the Protestant Struggle to Come to Terms with Darwin in Great Britain and America, 1870-1900. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979. Morton, A. G. History of Botanical Science: an Account of the Development of Botany from Ancient Times to the Present Day. New York: Academic Press, 1981. Overfield, Richard A. Science with Practice: Charles E. Bessey and the Maturing of American Botany. Iowa State University Press Series in the History of Technology and Science. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1993. Rodgers, Andrew Denny. American Botany, 1873-1892; Decades of Transition. New York: Hafner Publishing Company, 1968. Saunders, Gill. Picturing Plants: An Analytical History of Botanical Illustration. Berkeley: University of California Press in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1995. Secord, Anne. “Science in the Pub: Artisan Botanists in Early Nineteenth-Century Lancashire.” Journal of the History of Science 32 (1994): 269-315. Stafleu, Frans A. Linnaeus and the Linnaeans: The Spreading of their Ideas in Systematic Botany, 1735-1789. Utrecht: A. Oosthoek’s Uitgeversmaatschappij N.V., 1971. Stuckey, Ronald L. Development of Botany in Selected Regions of North America before 1900, Biologists and Their World. New York: Arno Press, 1978. History of Harvard In Economics of Harvard, Seymour Harris presented a discussion of how money circulated at the University; I used the volume to show that after the Civil War most of the money for the college came from alumni and benefactors. Education, Bricks, and Mortar presents a history of Harvard’s buildings and their uses, with a nice overview of the University Museum. Morison’s Three Centuries of Harvard provided a detailed history of Harvard, 122 organized along the lines of its presidents. I used it to learn about Harvard’s academic departments in the nineteenth century, and the financial and political situations therein. I used Robinson’s article to obtain an early history of Harvard’s botany program. Robinson provided amusing narrative and excellent explications of each academic division in the botany department. The article’s focus was to show the progress of the department, so the recent history in the article was all very positive about the different programs. I used the text Endowment Funds of Harvard University to find out the various funds created for the Harvard Botanical Museum and Botanical Garden. Endowment Funds of Harvard University 2 (Cambridge: Office of the Recording Secretary). Harris, Seymour Edwin. The Economics of Harvard. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970. Harvard University. Education, Bricks and Mortar: Harvard Buildings and their Contribution to the Advancement of Learning. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The University, 1949. Morison, Samuel Eliot. Three Centuries of Harvard, 1636-1936. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1936. Robinson, Benjamin Lincoln. “Botany.” The Development of Harvard University since the Inauguration of President Eliot, 1869-1929. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1930. Sources on Women History of Women in Science provided a variety of essays that gave me great background on what sciences women had access to and to what extent they could study science. Especially relevant essays were Sally Kohlstedt’s “Parlors, Primers, and Public Schooling: Education for Science in Nineteenth-Century America,” which argued that scientific education was deeply embedded in family life, reading experiences, and children’s schools—effectively becoming a lifelong phenomenon for people in the nineteenth century. Also, Margaret Rossiter’s essay in the volume, “‘Women’s Work’ in Science, 1880-1910,” looked at how women gained access to various sciences, as long as they were described and advocated as within the woman’s sphere of activities. Ann Shtier’s Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science, traced women’s involvement in botany as collectors, artists, and scientists. It argues that the professionalization of botany marginalized women. I used Shtier’s work to describe women’s use of botany in the home. Mary Louise Robinson described the histories of women’s colleges, with a special section on Radcliffe where she described its unique curriculum relative to other women’s schools. I used it to show what type of school Radcliffe was at its inception. Mario Biagioli’s book was not directly useful for studying women in botany, but I 123 used his argument that patrons are able to affect the course of scientific inquiry. Emanuel Rudolph’s survey on women in nineteenth-century botany was tremendously useful to my thesis; I used it to indicate plants of primary interest to women as well as descriptions of their educational backgrounds. Jessica Linebaugh’s undergraduate thesis discussed women’s contribution to botanical science purely in the realm of scientific scholarship, and provided an excellent bibliography of sources on women in botany. Biagioli, Mario. Galileo, Courtier: The Practice of Science in the Culture of Absolutism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. Kohlstedt, Sally Gregory, ed. History of Women in the Sciences: Readings from Isis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999. Linebaugh, Jessica Catherine. Beyond the Garden Gates: Amateur Women Botanists in America, 1860-1910. Undergraduate Thesis, Harvard University, 1997. Mary Louise Robinson, The Curriculum of the Woman’s College. Bulletin, Department of the Interior, Bureau of Education (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1918), 33. Rudolph, Emanuel. “Women in Nineteenth-Century American Botany; A Generally Unrecognized Constituency.” American Journal of Botany 69 (1982): 1346-1355. Shteir, Ann B. Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science: Flora’s Daughters and Botany in England, 1760-1860. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. 124