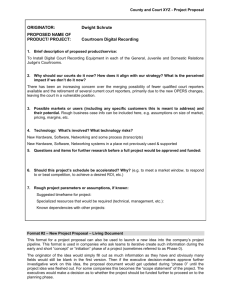

1 - UN Millennium Project

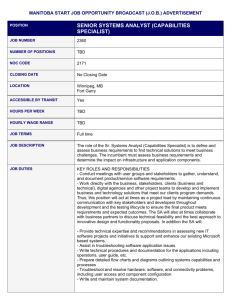

advertisement