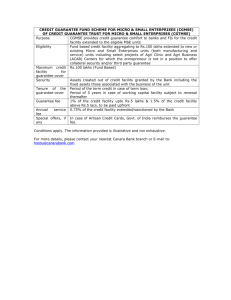

Credit Guarantee Scheme for Small Scale Industries (SSIs)

advertisement

Special Workshop on Sourcing and Financing of Technology for Small & Medium-sized Enterprises Credit Guarantee Schemes for SSI By N.Venkatasubramanyan Chief Executive Officer Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Small Industries 15:45 hrs –16:15 hrs December 4, 2001 APCTT, New Delhi Subramanyan" <nvenkats@hotmail.com> Credit Guarantee Schemes – A global perspective Banks view lending to small business as an activity with certain inherent difficulties and not a profitable proposition on account of – - high fixed cost element in appraising loan proposals; - problem of asymmetric information; and - inadequate collateral to compensate the risk proceeds In financial markets, which are subject to Government policy controls, small business is given a priority sector status for targeted lending. With deregulation and privatisation, direct lending per se may not be effective tool. Alternative mechanisms to be found to enhance credit to the targeted sectors. (1) Economic Function of Credit Guarantee Scheme: It is moot point whether guarantee schemes can be justified from a free-market economics perspective. Where there is market imperfection of some kind, requiring Govt. to address the need and to enable credit to targeted segments, Credit Guarantee Scheme play a role. Where there is no such subsidy element is involved, economic function of a self-sustaining guarantee scheme is to develop innovative products like securitisation of guaranteed loans. The key test of benefit of guarantee schemes is any additional lending to the targeted groups. The ideal guarantee scheme is one which helps banks gradually moving away from a completely risk averse stance towards SMEs. 2 As compared to other kinds of intervention, guarantee schemes have a number of attractive features. Savings are not being pre-impted and credit is not being subsidised. Schemes in principle are working with the grain of the market and not against it both static and dynamic sense because what is provided is guarantee capacity on the basis of credible reserve fund of some kind, and not the loanable funds themselves, considerable financial leverage can be achieved. Guarantee schemes are acting as a financial instrument for stimulating business development. Even though SME lending schemes have in the past, on occasions, proved ‘more risky’ and have involved a greater number of loan losses and defaults, in reality, experience in developed economies seem to indicate that with appropriate screening by the lenders / guarantors and effective portfolio management and debt collection, most SME portfolios have a default rate of less than 5%. In developed economies, the guarantee schemes have smaller subsidy element as compared to the economic gains. Understanding the political, economic, financial and competitive aspects of the environment in which the guarantee scheme is operating is essential, if any judgements are to be made about its contribution in relation to the objectives set out for it. The dangers are obvious in schemes which are politically driven, not set within a sensible economic policy framework, and which provides no commercial incentives for banks to undertake guaranteed loan activity. Where the guarantee scheme is set up as an instrument to channel funds to certain targeted groups without a serious 3 concern as to the loss rates to be incurred, guarantee funds are normally eroded quite quickly in these circumstances. (2) Economic context Whether guarantee schemes will work only during the period of buoyant macro economic conditions. There is no systematic evidence for this. It is true however; that the launching or relaunching of number of schemes in Asia, for example, in Japan, Korea, Indonesia and Malaysia were associated with a period of rapid economic growth, particularly export lead growth. Clearly as with all small business lending, default rates and hence claims rates are likely to rise during recessions, [e.g. Korea in 1990s]. This argument can in fact be turned around. With the guarantee organisation to observe some of the risks commercial banks may be more willing to lend to small firms during recessionary conditions. (3) Financial context In the 1970s & 1980s much small business credit in developing countries was delivered using public sector liquidity at subsidised rates [monetary policy being heavily interventionist with no freedom to banks to set interest rates for both sides of the balance sheets]. This resulted in excess demand and rationing inadequate spreads to cover operating costs. Banks had no incentives to select borrowers. Directed lending to SME sector is a policy stance in some developing countries. Targets are set by Central Banks in terms of percentage of Assets or Deposits or in absolute amounts. Sometimes penalty waiver, special levies of deposits to be held at the Central Bank or with refinance institutions. Guarantee Scheme may provide a legitimate means to help banks to fulfil SME lending targets if it allows a substantial part of the associated risks to be effectively removed from the balance sheets in return for a reasonable premium. Even if all or part of 4 the premium can be passed to borrowers, the level of participation in the scheme will normally be distorted and consequently so will its default rate. It is the Bank’s risk of borrower defaults that a guarantee scheme is designed to reduce [in Paraguay in 1970s, a Scheme supported by USAID, Banks were either unable or unwilling to lend their own funds to SMEs even with the guarantee which led to the collapse of the scheme] It can be made an attractive preposition if liquidity aspect is addressed. For example, in USA and Spain secondary market has been developed for securitisation of guaranteed loans. (4) The Competitive Context If there is little or no business incentive for banks to use a guarantee scheme, it will be active only to the extent that external regulatory or political pressure or public relations gains have an influence. SME borrowers represents potentially a significant segment of banks business. Though they represent a marginal market. As a general rule, banks, which have plenty of profitable opportunities outside the SME sector, are much less likely to adopt the guarantee scheme as a serious business strategy. Many schemes have low maximum lending limits and are restricted to small-scale borrowers as a part of the policy targeting. This restricts use of the scheme for upper end of the SMEs requiring larger finance unless banks are encouraged to collateralise such finances. Guarantee scheme in a fairly uncompetitive market can result in higher effective profit margin for banks because Banks pass on full guarantee premium to the borrower. However, some 5 schemes have restrictions on the maximum rates that can be charged; Where the guarantee scheme is well established in a competitive market, interest rates on guaranteed loans can be driven down by market forces so that the banks’ profit margin is reduced to reflect their lower risks, while the cost to the borrower, including the guarantee premium, will be only slightly higher than that of unguaranteed loans. [e.g. in Japan, Germany, UK and USA] II. ODA Study – Comparitive International Studies of Credit Guarantee Schemes (Source : Graham Bannock & Partners Ltd.) 1. 2. 3. 4. 1. Financial Instrument Target: Enterprise Group Target Form of Organisation and Funding Delivery Mechanism Financial Instrument Target Central thrust of guarantee schemes is the guaranteeing of lending for working capital needs, fixed capital investments or both. There are special guarantee schemes like Export Credit Insurance or Crop Insurance. These are outside the scope of our discussion. Eligibility of schemes are determined based on maximum loan size, minimum loan amount, borrower segment. Fixed Capital investment often may include land purchase, some schemes allow fixed interest rates, some both fixed and floating rate of interests. Certain schemes disallow lender from taking personal guarantee of the entrepreneur while others insist on it as it is not a collateral but it is evidence of commitment to repay. Some 6 schemes disallow third party guarantee and some partial collateral to be obtained. 2. Enterprise Group Target Variations here are the size, sector and age of the firms. Size is depend in terms of employment criteria, investment limit per turnover. Definition in terms of Employment maxima is prevalent in many countries. Financial services and real estates are the more common exclusions under guarantee schemes. In both advanced and developing economies, schemes restrict eligibility to firms, which are wholly, or majority owned. There are schemes which are targeted explicitly or implicitly or certain ethnic groups women or backward communities where a policy aim is to encourage entrepreneurship. Certain schemes in advanced economies are linked to policy objectives, environmental improvement [Norway and Netherlands] and encouragement or young entrepreneurs [Japan and Korea] A number of schemes in developing countries are narrowly targeted on transformation lending. 3. Form of Organisation and Funding There are unfunded schemes [pay as you go] and there are funded schemes. Once a separate fund is created, there has to be a minimum level of organisation and accountability. In UK and the Netherlands, guarantees are directly provided by Govt. Ministries through budget allocations. In the USA by the SBA, a federal agency. Where there is no separate guarantor organisation, the power to grant guarantees is often laid down in a piece of enabling legislation. 7 The constitution of Credit Guarantee Corporation may be subject of a special legislation [Asian countries and in Europe] or can be established under the General Rule of Financial Institutions, Credit Cooperatives, etc. The Corporation may be especially exempt from tax as a nonprofit organisation or been subject to favourable treatment, if tax exemption is not given. Where guarantee organisation qualifies as a body owned by Sovereign Government, banks do not have to reserve against liabilities it has guaranteed [India]. Donor agencies, bilateral, multi-lateral are involved in providing technical assistance for setting up as also in contributing to the financial capacity of the guaranteeing organisation. [Poland backed by PHRD, Kenyan Scheme backed by ODA, Peru scheme backed by Netherland Aid Programme] Financial structure of the funded credit guarantee organisation can take various forms. In some cases banks are shareholders. In some cases, establishment of the guarantee corporation is initiated by the banking authorities or at the behest of the government initiative. Funding to the Credit Guarantee Corporation is provided through special borrowing on short terms and grant support from govt. sources. The financial engineering of the corporation is a key factor in determining its guarantee capacity. It cannot borrow on commercial terms from the financial sector or has the capacity to tap the market directly. Credit Guarantee Corporation provides other services to SMEs such as management consulting and earns fee-based income. 8 Mutual Guarantee Organisations [MGO] are contributed by members of SMEs, Chambers of Commerce, Trade Associations, Development Agencies and local Govt. bodies. The mutual form of organisation for the guarantee issuing institution though founded and working well in Europe, the concept has rarely been exported to other parts of the world. Attempts to do so in West Africa have not been successful [Balkenhol 1992], a Scheme in Kenya supported by KfW, Germany and USAID collapsed in 1985 while another in Philippines has not progressed well. The participation of the banks, which utilise guarantee services as partners in the equity of a national, or a regional guarantee corporation is quite common feature of recently created schemes in both advanced and developing economies. The most complex schemes involve more than one tier of guarantee organisation. The upper tier at the National level provides reinsurance or co-guarantee to the lower tier at Regional or Local level [Japan and Spain – Two Tier Systems]. Developing country schemes tend not to have genuine reinsurance elements. GCs used as a channel to reimburse banks on losses they have suffered from onlending on govt. sponsored credit programmes. A unique organisation form, which provides no domestic guarantee funding capacity, is the Loan Portfolio Guarantee scheme [LPG] operated by USAID. This is a series of international bilateral commercial guarantee agreements between a dept. of USAID called the Centre for Growth and some 60 individual commercial banks in 20 or so countries. The arrangement allows for the maximum guarantee facility, lasting initially for three years but renewable, in multiples of USD 0.5m, out of which the bank can allocate risks from its portfolio of eligible loans. Banks pay one time facility fee of 9 0.5% and a quarter usage fee, which varies from 1.5% to 2% p.a. The risk is sharing percentage is 50 in case of normal loan and upto 70 in case of loans to micro enterprises. 33 countries have so far benefited by the LPG programme. Geographical distribution of the portfolio has been in the order of 32% in Africa / Near East Region, 36% in Asia, 27% Latin America and 5% in Europe. Schemes, whose delivery mechanisms, in a variety of commercial and financial environments, have allowed them to achieve a high level of activity, without running into financial problems, are the most important models. This implies that there is a successful balance between incentives, risks, responsibilities and financial capacity. 4. Design Features A variety of types of guarantee schemes having different objectives and working in different environments are being implemented in various parts of the globe. Nevertheless, there are some necessary conditions for a guarantee mechanism to be effective and sustainable. These are : Banks can make profitable guaranteed loans to the target population. Risk is shared between the borrower, lender and the guarantor The level of guarantee coverage reflects the risks Guarantee Fees are high enough to prevent banks using the guarantee for loans that do not need it, but low enough not to put off borrowers. Fees and investment income for the guarantor are high enough to cover expenses and defaults The guarantor is credible; pays out quickly and in welldefined circumstances. Lenders achieve good repayment through prudent loan screening, monitoring and collection procedures. 10 Banks desired to work with the target group, but lacks experience and information. Design features are grouped under the following headings: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Eligibility Criteria [Lenders / Borrowers] Risk Sharing Delivery Mechanisms Governance of Guarantee Organisation Composition of Guarantee Fund Fee Structure Once goals are set for a Guarantee Organisation, the need to have a coherent marketing plan to achieve them, either by direct communication with the targeted SME groups or through the banks as the distribution channel becomes a primary focus. There is also a need to monitor the progress and adjust the strategy accordingly. Following are the steps involved in running a guarantee operation. 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) Marketing the guarantee service to lenders and to SMEs Approving applications for guarantee cover Issue of guarantee cover. Claims handling Post claim loss recovery Managing guarantor – lender relations. The marketing messages to lenders need to emphasise: The commercial benefits in terms of increased profitable business. The simplicity and low cost of the guarantee issuing procedures. 11 The credibility of the guarantee and the clarity of payment triggers. The high standards expected of lenders in extending credit, monitoring and recovery of SME loans. The marketing stance has to be backed up by delivery of efficient performance in processing guarantee transactions and in meeting claims; otherwise the trust of lenders can be lost. Marketing activity cannot be separated from education and training. Many schemes around the world have adopted the practice of holding regular small-scale seminars for local bank managers and representatives of the SMEs and of offering training materials for use by the banks’ lending officers. The lenders can be requested to set a minimum target of guaranteed loan transactions per branch, so that this will ensure that all branches have some familiarity with the guarantee scheme. Most powerful is demonstrating that the guarantee scheme contributes significantly to a branch’s overall performance. The marketing message has to be very clear, particularly to the borrowers. It should not give a signal to borrower to increase the danger of moral hazard by allowing any suggestion that the scheme enables people to obtain bank credit, which does not have to be repaid, because default will be refunded by a public body. 5. Approving applications: There are two routes. One is automatic guarantee cover. Another is screening of individual proposal. Where there is an accreditation so that banks are free to approve eligible loans for guarantee without prior referral to the guarantor, the automatic route is followed. On a fully automatic 12 scheme (Indonesia, Pakistan), there is little or no information flow to the guarantor except when claims arise. Fees are based on priority sector lending declarations to the Central Bank. Where the procedure requires guarantor’s prior approval, two variance are possible. Either the borrower approaches the guarantee first and obtains a certificate, which can then be used to negotiate a loan with an accredited bank. Or bank is well aware of the eligibility norms / conditions of the scheme and uses the standard form (specified by the guarantor) to cover all necessary points in a checklist. This form is then forwarded to the guarantor for approval of guarantee. The form should be designed ideally to provide all the information that bank requires for loan underwriting as well as the guarantor’s need so that information is recorded once only (in providing technical assistance to the newly set up guarantee scheme in various East European countries, notably Slovakia, Slovenia, Czech republic, Hungary and Romania, the Austrian Burges Forderungsbank paid considerable attention to optimising documentation and decision making procedures. 6. Claims Handling: a. Default events triggering claims b. Claims validation In early guarantee schemes initiated in developing countries tended to ignore putting into place suitable procedures with adequate staffing for handling claims for payment of guarantee. There is a need to have clarity in determining the default events triggering claims. When drafting the claims trigger conditions it is vital to have a realistic perception of practicable and time scale of legal recovery processes Proof that legal processes have been initiated by bankruptcy or asset recovery may be a 13 more reasonable standard than obtaining judgement in many countries. The arrangements for triggering and validations of claims should work in a complementary manner, and a more stringent approach to validation can be justified where guarantee approval has been delegated under a portfolio arrangement. The most common trigger event is fixed period after the occurrence of a single missed payment of a amortisation instalment (commonly known as NPA norms, set by the Central Bank of a country). Trigger events can include a medium period from laon disbursement before any claim is admitted (lock in period). This can deter over credit appraisal of short-term loans by lenders. The toughest trigger condition is to prefer claim after all legal processes have been exhausted.(Israel, Egypt, Morroco) The severest validation is one where every claim is subject to documentary audit before payment is made (Pakistan). There are schemes, which require ex-ante validation only for larger claims and use a random or occasional procedure expost for smaller claims. In principle, some rejection rate is desirable to keep bank procedures under discipline, but very high rejection rates are usually a sign that things are going wrong. 14 Reasonable requirements for triggering a claim payout are proof that the following have occurred: Arrears and non-payments of loans for 90 days Lender has contacted defaulters, sending out warning notices on time Calling in of total loan after time has lapsed and warning given and ignored Writing-off of loan in accounts of lending institution Initiation of legal steps to foreclose on any security (primary or collateral) and for recovery of loan. 7. Interest element in claims Typically the best schemes allow interest up to the date of the default event (NPA determining date). Some schemes permit interest on term loan and working capital loan. In some schemes, interest on term loan is not permitted to be covered under the guarantee requiring the lender to bear the risk. 8. Post claim loss recovery Guarantor in some schemes exercises subrogation rights, whereby; the responsibility is assigned to the guarantor for recovery from sale of assets of the defaulter borrower. In some schemes, it is responsibility of the lender who has better control over / access to the borrower. While post claim recovery rate is as high as 54% of the subrogated amount (Japan) and ranging from 22% – 25% in other developed economies (Korea). The recovery is as low as 7% (India). 9. Managing Guarantor Lender Relations Success of guarantee schemes depends first and foremost on obtaining the collaboration on participation of the lending banks. 15 Many failures of the earlier guarantee schemes in many countries occurred because the banks were reluctant to take part, not holding the guarantee to be credible or cost effective. Both the parties have to be responsible in playing the respective roles sincerely. The guarantor should approve guarantees and settle claims without delay. The lender should also take due care in apprising loan request, adequately supervise the borrower and should not fail to pursue debt collection vigorously. More recently guarantee organisations have become aware of the need to generate confidence in the banks and have spelled out in much greater detail the situation and procedures for defining their respective roles and relationships and for obtaining practical cover under the guarantee. This situation can be helped greatly if the guarantor itself has a structure allowing participating banks a voice in its operational arrangements. Conflicts of interest, which might occasionally arise on an individual transaction basis, should not prevent this relationship from being fruitful. Where the scheme is participated by several banks, comparative monitoring of individual lender is possible, examining reasons for larger claims and if the lending behaviour is in any way falling below agreed standards in the banking industry or breaking any eligibility condition, this can be dealt with by reducing the coverage or increasing the guarantee fee for the particular bank. At times, accreditation rights or even complete participation may have to be curtailed at least temporarily while the problem is investigated. The ability of the banks to benefit commercially, directly and indirectly from their use of guarantee scheme is of course paramount and it is an issue, which the guarantor must have in mind, in managing the relationship. 16 The cost of administering the guarantee scheme can be reduced by use of technology or appropriate software. The data compiled by guarantor on the defaulted borrowers can be shared with the lenders. There could be interest rate ceiling restricting the spread of the lender so as to ensure cost effective lending to help a targeted segment of entrepreneurs (first generation / young / women entrepreneurs). However, in a competitive market place there may be exceptional cases where interest ceilings are justified. 10. Managerial competence Well-designed schemes can be badly implemented and fail if the resources to introduce and manage them are inadequate. Guarantees are a relatively sophisticated financial instrument, and running a fund on a sound actuarial basis in difficult or unstable economic or financial conditions is not easy. The ability to negotiate guarantee arrangements either on an individual transaction or ona portfolio basis with commercial bankers, who may be very experienced and seeking a financial advantage, is a clear requirement for guarantor staff. A key requirement is for the guarantee to be credible to bankers. Partly this is a matter of design, for example in the setting of fair and transparent conditions under which a claim will be met. Partly though, it is a matter of sound management. Payments to meet claims need to be made promptly and according to the rules. A banker’s trust is hard to earn, and once lost even harder to recover. Lenders accredited to the guarantee scheme need their lending, delegated approval, and delegated post-claim recovery activities monitored. Adequately marketing the scheme directly, or through lenders, to the target group can be particularly difficult to achieve cost effectively. The question of whether or 17 not the organisation should have its own branch network is relevant here. People with the right level of commercial and financial experience have to be attracted and offered appropriate rewards and career development opportunities in the guarantee organisation. It is quite common for the guarantee organisation to offer additional services to borrowers or lenders. These may include credit references, project appraisals, business plan preparation, and training of bankers and / or SME managers. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 18 Indian experience of Credit Guarantee Scheme Since 1960, a Govt. sponsored scheme administered through a special Section of the Central Bank of the country, the Reserve Bank of India, had been providing credit guarantees to small scale industries as defined in priority lending targets. Schemes were designed for meeting the needs of specific borrowers viz. industrial borrowers and non-industrial borrowers. There were two large schemes, small loans guarantee schemes 1971 for small non industrial borrowers and small scale industries schemes 1981 for units covered by the small scale industries definition which includes cottage, khadi, village industries and artisans. The scheme participation was made mandatory for the lending institutions, which was relaxed for SSI scheme. Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC), a wholly owned subsidiary of Reserve Bank of India, operated the schemes. The schemes were operated on an automatic bulk coverage basis. The guarantee fee was payable in advance at 2.5% for small loan guarantee schemes and 1.5% for SSI schemes, respectively on whole of the outstanding balance under priority sector advances. The guarantee cover, which was initially for 90%, was brought down to 60% by 1985. The claims were not allowed until a 3-year period has passed from disbursal. From 1995, before a claim was preferred the bank had to write off the loan rather than treating it as a bad and doubtful of recovery. Both schemes have operated at a very high volume of claims activity, probably because banks could achieve at least some recovery for losses on the huge volume of directed lending to the priority sector. Though, the guarantee schemes served their purposes in the initial period, owing to limitation of the capital base and investment income, it could not meet the claims 19 demand. Further, on account of blanket automatic route, many loans were also reportedly unwritten by banks without due diligence. Certain stringent conditions were brought in to discourage excess claim activity. By early 1990s, the guarantee scheme had lost its flavour as many banks had started withdrawing their participation. The S.L. Kapur Committee, appointed by Reserve Bank of India to look into the credit related aspects of SSI, recommended that the DICGC Scheme be scrapped and replaced by a more objective and suitable scheme to be operated by a new Corporation. The Committee while making recommendation had in its view the guarantee scheme being operated by SBA. The Committee also recommended that the new Corporation should cover all loans sanctioned by public sector banks and financial institutions where the principal amount does not exceed Rs.10 lakh. According to the Committee, the new Corporation should have a corpus of Rs.500 crore to be contributed by the Govt. of India, SIDBI, NABARD, State Governments and Commercial Banks. The recommendations of the S.L. Kapur Committee have been examined by the Govt., which felt a need for launching a new credit guarantee scheme to address the particular issue of problems faced by tiny units in the small-scale industry in arranging collateral security for accessing formal banking credit. This initiated the process of launching a new Credit Guarantee Scheme for Small Industries. 20 Credit Guarantee Fund Scheme for Small Industries The small industries sector, which has a wide spectrum of industries in small, tiny and cottage segments, plays pivotal role in the development of Indian economy. Though the contribution from SSIs has been significant to the overall economic development of the country, the sector has been beset with certain handicaps. One of the main problems is non-availability of adequate credit from the banking system without collateral security or third party guarantee. To resolve the problem, the Ministry of Small Scale Industry, Govt. of India, in consultation with Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) formulated the Credit Guarantee Fund Scheme for Small Industries (CGFSI). The objective of the Credit Guarantee Scheme is to guarantee the loans and advances up to Rs.25 lakh so as to help the new and existing industrial units in the SSI sector including units in Information Technology and Software Industry, in getting collateral-free/third-party guarantee free credit from eligible lending institutions viz. Scheduled Commercial Banks, select Regional Rural Banks (RRBs) or such of those institutions as may be prescribed by the Government. Eligible RRBs are those, which fall in the category of ‘sustainable viability’. The scope of the Scheme with regard to eligible activity, eligible institutions and eligible credit ceiling may be modified depending on the needs. The guarantee cover under CGFSI is available for credit facilities extended by eligible lending institutions, in respect of a single eligible borrower, not exceeding Rs.25 lakh by way of term loan and / or working capital facilities after entering into an agreement with the Trust. CGTSI provides guarantee cover of up to 75% of the amount of the credit facility extended by the 21 lending institution to an eligible borrower, subject to a maximum guarantee cover of Rs.18.75 lakh per borrower. 1. Guarantee Fee and Annual Service Fee The Trust charges one time guarantee fee @ 2.5% of the amount sanctioned by the Member Lending Institution and annual service fee @ 1% p.a. on the outstanding amount, as on 31st March of every year, to the debit of the borrower’s account, covered under the scheme. 2. Administrator of the Scheme GOI and SIDBI, who have executed an Indenture of Trust, set up Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Small Industries (CGTSI) on July 27, 2000 to administer the Scheme. The Trust’s registered office is at Nariman Bhavan, 227, V.K. Shah Marg, Nariman Point, Mumbai-400 021. Website www.creditguarantee.org.in 3. B2B on-line transactions Transparency and real-time service to the customers are the two sides of technology based operating environment. Towards this end, CGTSI operations are crafted in tune with the emerging trend. CGTSI has taken steps to set up a fully integrated on-line system that can process variety of transactions in large volumes and cater to customer information more efficiently. 4. Corpus Fund of CGTSI During FY2000-01, GOI and SIDBI contributed Rs.125 crore in the ratio of 4:1 towards the Corpus Fund of CGTSI. The settlors have contributed Rs.75 crore in 2001-02, thus increasing the fund to Rs.200 crore. The Settlors have agreed to enhance the corpus fund of CGTSI up to Rs.2500 crore, in the coming years, depending on the needs. 22 5. Member Lending Institutions Since October 2000, eligible institutions have started becoming Member Lending Institutions (MLIs) of CGTSI. As at the end of October 31, 2001, 18 Public Sector Banks viz. Allahabad Bank, Andhra Bank, Bank of Baroda, Bank of India, Bank of Maharashtra, Canara Bank, Central Bank of India, Corporation Bank, Dena Bank, Indian Bank, Indian Overseas Bank, Punjab National Bank, Punjab & Sind Bank, Oriental Bank of Commerce, Syndicate Bank, UCO Bank, Union Bank of India and Vijaya Bank and 2 Private Sector Banks viz. HDFC Bank and IDBI Bank have become MLIs of CGTSI. Besides, two Regional Rural Bank, Sri Saraswathi Grammena Bank, Adilabad and Prathama Bank, Moradabad, have become MLIs of the Trust. As prescribed by GOI, NSIC and NEDFi have also become Member Lending Institutions of the Trust. 6. Implementation Status of the Scheme as on October 31, 2001 Total No. of MLIs – 24 Active MLIs – 13 Units covered under the Scheme – 2143 Credit covered under the Scheme – Rs.16.33 crore Project outlay of these units –Rs.23.62 crore Expected sales turnover – Rs.88 crore Employment generation by these units – 4898 persons 23 Mutual Credit Guarantee Scheme While the existing credit guarantee scheme operated by CGTSI would help the lending institutions to assist SSIs in extending credit without taking any collateral security, the question of containing or minimizing the default rate is still to be addressed. In such a situation, besides close monitoring of the assisted units and maintaining better customer-relationship, a sort of guarantee forthcoming forward from an Industry Association, in which the borrower is a member, would certainly enhance the lender’s confidence level. Perhaps, Project Screening Committee of the Industry Association could select the proposals of its members based on merits before passing on the same to the bank for financial assistance. In such a situation, the peer-level pressure brings in certain amount of discipline among the borrowers in proper conduct of their accounts. Such a measure will go a long way in increasing the quality credit flow to SSIs. In this backdrop, CGTSI proposes to experiment with the successful Italian model of Mutual Credit Guarantee Scheme (MCGS) and introduce a suitable model for India. Under MCGS, an Industry Association creates a Mutual Guarantee Fund (MGF) through contributions from its member industrial units. The corpus of MGF is leveraged by the Industry Association to extend credit guarantee in respect of loans sponsored by it and extended by a bank. CGTSI would extend counter guarantee to such guarantees extended by Industry Association so that it would enhance the credibility to the Associations as also flow of credit to the targeted sector. ---------------------