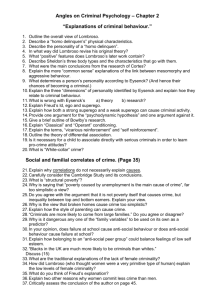

Forensics Textbook

advertisement