Codes_inventory_r

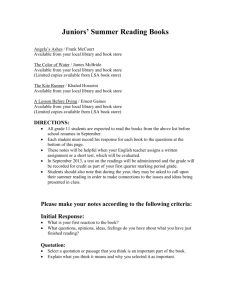

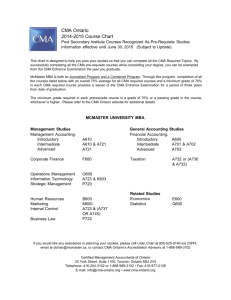

advertisement