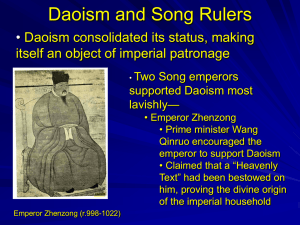

Daoist Alchemy in the West

advertisement