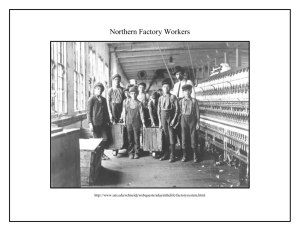

William Dodd, The Factory System Illustrated

advertisement