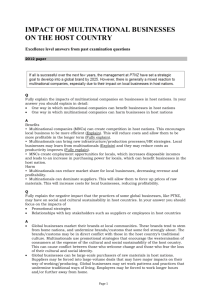

Corporate activity in Puerto Rico: Westinghouse responds

advertisement