What Is Long-Term Care? - Continuing Education Insurance School

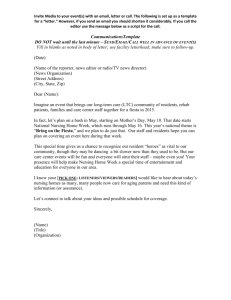

advertisement