07. The Etruscans

advertisement

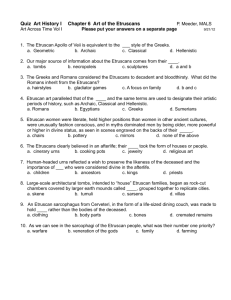

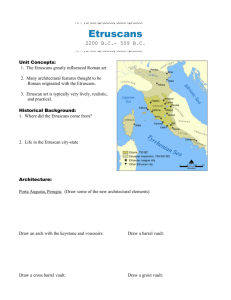

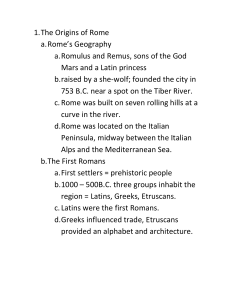

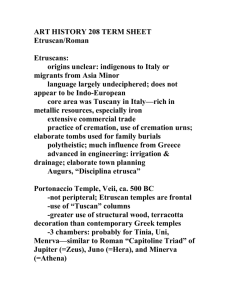

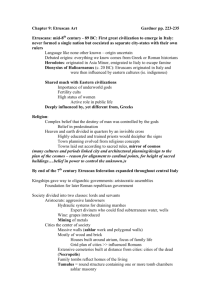

The Etruscans—Tutors of Rome Around 800 B. C. a mysterious culture appeared on the Italian peninsula. We still don’t know from whence they came or fully understand their language. Yet for three hundred years, until 500 B. C. when they were absorbed by the Latin people they once ruled, their civilization flourished to such an extent that many of the ideas and images we associate with Rome were actually adopted from these first overlords. The mysterious people were known to Romans as Etruscans, and while it is said the Etruscan culture was essentially Greek in nature, their origins have been lost. Among the attributes of Rome borrowed from the Etruscans are ideas like gladiatorial combat as a spectator sport; the arch; the ivory rod, a short, simple throne, and the purple toga as symbols of authority; and religious ideas like augury. Augury is the art of divination from “omens.” Chance events were interpreted as signs of the future including seeing a sea bird over land, observing lightning, or finding a tree that had split. When chance events did not present themselves, augurs cast lots or inspected the internal organs of sacrificial animals looking for signs. Even towns were bequeathed to the Latin people by Etruscans. Rome itself began as an Etruscan town and became a great city atop its seven hills under Etruscan rule. As we investigate the culture and history of the Etruscans in Italy, remember we are actually laying the foundation for our study of the Roman Empire as one of the great empires of all of history. Having experienced Greek-like culture, Romans were prepared to assimilate Greek culture when Rome competed with and ultimately conquered the Hellenistic people left behind after the death of Alexander the Great. As the Romans conquered the known world, their empire building talent proved equal to that of Alexander and the Persians in borrowing what was interesting from conquered cultures and otherwise letting those cultures carry on. For example, the ritualistic religion of pagan Rome was adopted from the Etruscans’ which was adapted from the Greeks’ which was modeled after Egyptian religion. We have danced around Italy without formally introducing you to the geography of what would function for centuries as the center of the Earth. Italy, of course, lies on a long boot-shaped peninsula jutting out into the Mediterranean Sea. The peninsula is choked with rugged mountains that divide Italy lengthwise. Three lowland areas are all that presented themselves as cradles of civilization—the Po River valley that almost makes Italy an island by cutting across the north; the area at the mouth of the Tiber River called Latium, where Rome was born; and Campania in the south resting atop the toe of the boot. The mountains that dominate all the rest are called the Apennines. An ancient historian said, “So the land, so the men.” The earliest residents were as rough as the land. The Latins were invaders from the north who came between 1,000 and 900 B. C. The future world-conquerors began as wandering Indo-European herdsmen. Then suddenly around 800 B. C., an immensely gifted, original, warlike, hard new wave of invaders arrived for whom Italy seemed just the place. The Etruscans were the first civilized people to abide in Italy, and they chose the mountains north of Latium to call home, or Etruria. The mystery of the Etruscans is that ancient historians disagree as to who they were. Herodotus said they were Lydian colonists from Asia Minor because it is reported that during a famine the Lydians divided their population for survival and sent half away. But Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who was from Ionia on the Aegean Sea, observed, “They don’t speak Lydian or worship Lydian gods.” But the art is similar. Wherever the Etruscans came from, they immediately produced a thriving culture in Italy based on farming, fishing, and commerce. The farming was especially important because it would give the Etruscans something the Latin herdsmen did not even desire yet—cities. These adventuresome colonists fortified hilltops all over Italy as the sites of their first towns. From 700-600 B. C. they expanded to the Po River in the north and to Sicily in the south where they ran smack into Greeks. The Etruscans preferred another colonial power for trade partners and allies against the Greeks and befriended the Phoenician colony of Carthage in North Africa. In conflict with other cultures, the distinct Etruscan advantage was iron. Their use of iron weapons and tools is another reason they remain mysterious, though, because their artifacts rusted away unlike those of their Bronze Age neighbors. Etruscans possessed a written language that we have yet to decipher. What words we think we know link up into incomprehensible idioms with way too many consonants. Their written language, though, gave them a law code and sophisticated instructions on how to interpret the condition of entrails in augury as well as a 16-segment map of the sky to discern the future from forks of lightning. Their language even influenced English in that around 100 of our words are reported to have come from Etruscan through Latin, including persona, antenna, and cup. The exceedingly impractical practice of gladiatorial combat is said to be associated in Etruscan religion with providing blood for a corpse during funeral rites. A more practical bent is revealed in the fantastic civil engineering feats of the Etruscans including digging tunnels through hills, draining lakes, diverting rivers, and building smelting furnaces. The arch is nothing to sneeze at, especially while you are building one. These bold seafarers ventured into the Atlantic Ocean, and their pursuit of adventure and fun produced horse racing, satirical theater, and dancing. As seen in the embrace of the reclining couple in the terra cotta sarcophagus, women in Etruscan society were treated as happy equals. Women were free to participate in politics. Neither the Greeks nor the Romans approved. Even the Greeks were shocked, too, by the sexual promiscuity of Etruscan women who practiced open sexual relations with whatever men pleased them. Having the capacity to embarrass ancient Greeks with sexual practice is revealing, and Etruscan sexual license destabilized their civilization. Few Etruscans knew who their fathers were. Regarding political practice, Etruscans ultimately founded twelve city-states, each with a prince known as a lucumon who was also a high priest. These princes adopted god-like demeanors and trappings of royalty that were all transmitted to Roman rulers. A Roman historian said that Etruscans were the “authors of that dignity which surrounds rulers,” and the aforementioned ivory rod and togas added to the pomp of ceremonies. Even the bronze eagle atop the military flagpoles and the red cape associated with Roman generals are both Etruscan in origin. You have observed the sculpture of the Etruscan people to be sinewy, lively, and evocative of a culture dominating its world. Fancy tomb wall paintings also depicted boisterousness with musicians, dancers, wrestlers, jugglers, horsemen, embracing lovers, chariot races, and bullfights. This last subject reveals a lasting impact of Etruscan culture in that Spain’s dramatic death-dance was handed down by the Romans from the Etruscans. The least appetizing artistic legacy of the Etruscans is in the architecture of their temples which were Greek-like but crudely formed and decorated only on the façade. After three centuries of dominance, the Etruscans went the way of all flesh. In the denouement of their culture, the Gauls, who would later make Julius Caesar famous, invaded from what is today France. The Etruscans appealed to the Latin people of Rome to save the country. As Carthage began to expand as an empire and repulsed Etruscans from Sicily, the Etruscans appealed to the Latin people of Rome to save the country. Then minor tribes rebelled, and the Etruscans appealed to the Latin people of Rome to save the country. By then the Latin people of Rome caught on and revolted in 509 B. C. and deposed their Etruscan rulers. Watch for this same pattern again, however, in Rome’s own demise about 1,000 years later. An empire building strength of Rome, however, is revealed in the ten-year siege of the Etruscan stronghold of Veii. The former Latin herdsmen used cavalry and armor against their masters who had tutored them in the use of cavalry and armor. Rome was not founded by Romans but it was captured by this people who could learn from their enemies. Watch for that pattern again, too. By 82 B. C. most living, distinctively Etruscan people were massacred by order of Sulla, a Roman general you will meet again. The Etruscan language was lost by the second century A. D. The Roman Emperor Claudius could speak it with his Etruscan wife, and he wrote a twenty-volume history of the Etruscans, but that was lost, too. In 1964, three golden plates were found with Punic (Carthaginian) parallel texts like the Rosetta stone for Greek hieroglyphics, but no breakthrough has occurred yet that might open up more of the Etruscan’s mysterious past.