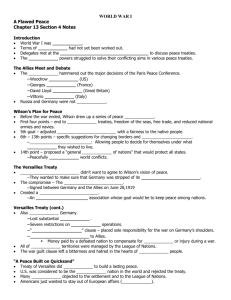

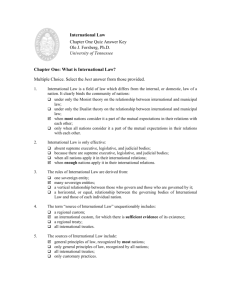

EU legal character

advertisement