Lincoln Square Urban Renewal Area Project

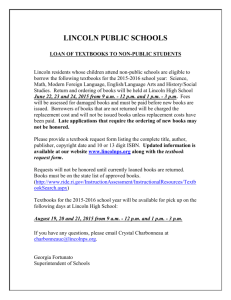

advertisement