Introduction to - John Birchall

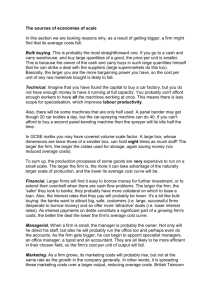

advertisement