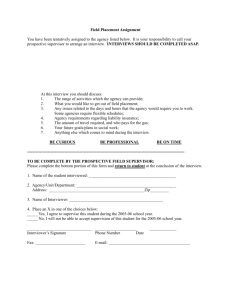

Interview Format This specialized interview technique is designel for

advertisement

Witness to Violence: The Child Interview

ROBERT S. PYNOOS, M D., M.P.H., AND SPENCER ETH, M.D.

In this paper, we present a widely applicable technique of interviewing the traumatized child who

has recently witnessed an extreme act of violence. This technique has been used with over :00

children in a variety of clinical settings including homicide, suicide, rape, aggravated assault,

accidental death, kidnapping, school and community violence. The easily learned, three stage

approach allows for proper exploration, support and closure within a 90-minute initial

interview. The format proceeds from a projective drawing and story telling, to discussion of

the actual traumatic situation and the perceptual impact, to issues centred on the aftermath

and its consequences for the child Our interview format is conceptualised as an acute

consultation service available to assist the child, the child's family, and the larger social

network in functioning more effectively following the child's psychic trauma.

Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 25, 3:306-319,1986.

Although there has been a growing awareness of the

importance of work with traumatized children such as

victims of physical or sexual abuse and kidnapping,

there is a larger population of children who have been

witness to violence, and suffer from the aftereffects of

that psychic trauma (Pynoos and Eth, 1985). For

example, the Sheriffs Homicide Division of Los

Angeles County estimates that dependent children

witness between 10 and 20% of the approximately

2,000 annual homicides in their jurisdiction.

It is difficult to imagine a more harro wing experience than for a chiid to witnes a parent 's murder,

suicide or tape. Anyone who has attempted to assist

children who have recently been so traumatized wilt

onderstand the difficulty in knowin how to roteed. The

chiid mat' exhibit mant' of t e c aractens ics o an acute

posttraumatic stress response. As a result, he ( * ;he ran

present ac minti nr muto Direct inqu ry ibout the traumatic

event mat' be unproductive, leaving the interviewer

feeling stymied and the chiid further entrenched in

de',achment. In addition, the chiid wilt frequently be in

a state of mourning for the lost patent, further

complicating the clinical interview.

In this papier, we describe an initial interview tech

Rece« rd .!0. 19a33: aeeepted April ~. 1983.

Dr. Pvnoos j Director. Program m Preuentwe lntervention i n

nique that has proven successful in heiping a psychiatrie consultant to engage

young children in conversation shortly after witnessing a traumatic or violent

event. It is intended for use witti children Erom 3 to 16 years of age. This

technique enables the interviewer to gain insight info the chiid's

onderstanding of the event and to characterize the behavioral and emotional

responaes in order to provide specific professional support to the mild reen

after the trauma. The interview technique has ondergors a series of revisions

as oor experience has groven, and particularly as we have teamel from the

children's oven comments about the interview. The interview bas proven to be

a gerent technique applicable for ure witti children who have witnessed

murder, suicide, rage, accidental death, aggravated assault, kidnapping, and

school or community violente. To data, we have employed it witti over 200

childen. ln addition, tor interview format has been readily taught to

other~iental health professionals who have themselves suceessfully used it in

a variety of clinical settings.

Tra4ma. Vu)lenee • and Bereauement ~n Childhc.w4, Dwiswn of Child P~~chuurv and . s.IL$tant Professor. Prvchuury and Bwo ehaviorai Sccences. L

'CL4- Netsmpsyehwtru Institute. 760 Westurood Pta.:a, Los Angeles, CA

90021, wherr reprinu inay be requested Dr. Eth is .4 sistant Professor.

Interview Format

Psvchiatry and Biobehauwral Sciences, C'CLk.Vesropsvcheatne fnstitute and

Ciinual .4ssutant Professor of Psychwtrv and the Behat'wral Sciences,

This specialized interview technique is designel for ure in rhe initial

C'nwersuy of Southern Caiifornfa.

meeting

witti a recently traumatized chiid. It is presented here as a coherent

The authws w sh to thank Drs. Theedon Shapiro, Robert Michels and E.

James Anthony for their :houghtfW ~-omments on oor werk, and Jar ue

three-stage proces: opening, trauma, and ciodure. The format

Berman for her elitemal and ;ecretarial support.

u beisra bv permittint the chiid fust to expres thé

~»u2 138/S612503 .4306 $02.0010 x;1986 by the American Academy of

Child Psychiatry.

im ct of th trau a

instaphor, bv ure of a Droiective free drawin, and story telling taak. This

opening enables the consultant to appreciate the child's preliminary meen of

coping and defensive maneuvers. Second, the interviewer shifts attention to the

actual traumatic episode. In order to Foster masterg of the traumatic anziety,

he , overcomes the efforts of the chiid to avoid and leng.

306

WITNESS TO V1OLENCE: CNILO INTERVIEW

and supports a thorough exploration of she child's

experience. Finally, she consultant can then assist she

child in erfdressing his or her current life concerns witti

an jncreased sense of security, competente and

rnasterv. As witti any clinical interview, she sugges order

may be modified somewhat as a function of she child's

particular responses, bot it is important to adhere to

she general format. Each major step in she interview

proces may be doplood through a series of drawings. In

out experience, she entire interview requires

approximately 90 minutes.

Prior to she interview, it is important to have obtained Erom she family, police or other sources some

description of she family circumstances, she violent ,

event, and she child's subsequens behavior or re sponses. The interviewer can then be alert to important

references or omissions in she child's account.

____________ First S tage: O pen in g

Establishing she Focus. After greeting she child in out

usual way, we share that we have had experience in

talking to other children who have "gone through what

you have gone through." Others can say that they are

interestel in onderstanding witti she child what it was

like to go through what he or she hes been through. By

making that statement, we establish a fixus tor she

interview, inform she child that he or she Is not clone in she

predicamenc~; and offer some ego support to she child

byour willingness to look logether at what hes occurred.

After these preliminary comments, we do not find it

necessarv or heietui to have other persons, e.g., family,

relatiees, or guardians present. We see each child clone

in a auiet room

Free Drcwing and Story T e l l i n g . Upon being seated,

she child is Biven pentil and paper, and askerf to "draw :

hatever you'd like bot something you can telt a story,

about." The child is reassured that she Quality of she

drawing is of no concern, and allowed to approach she

taak without disstadion or interference. By ~tepping

aaide she interviewer may entourage she child to

altend tune to she creative work. All she children have

spelled themselves to stils taak, although these may be an

initial period of hesitance. The youngest chil

dren, show onder 4 years of age, are engaged in play

along witti their scribbling and are askerf similarly "to

make up a story." Our emphasis is tor she children to

begin in whatever menner is moet acceptable to them.

This approach allows for she child's imagination to be

temporarily rollevel from reality and superego constraints (Waelder, 1933). The children we have seen

have energetically taken to this activity even hours after

witnessing a violent ovens. The drawings and stores

eert' considerably in their projective style and content,

from examples of nearly direct accounts, to richly

endowed works of fiction.

Children appear to be more comfortable witti thie

mannet of therapeutic engagement than she alternativo

style of direct inquiry. This opening is seen ultimately

to facilitate a later open discusion of she

traumatic occurrence.. The interviewer hopes by his

erpression of interest, level of enthusiasm, and occasional playfulness, to entourage the child to regain more

spontaneity. This step begins she proces of toontering

30?

she passive, lesschel stance of she traumatized witnes. The

interviewer entourages she child to elaborate further on

both she drawing and story. This can be done by general

questions, i.e., "What kappens next?„ or by inquiring about

some eedion or detail. Elaboration usually shows she

interviewer to gein an initial appreciation of she child's life

circumstances.

Treurneut Ref erewee. The key concept in this open

g ing stage is that she violent ovens remeins intrusive on

she chi!d's mind and wilt be represented somewhere in she

drawing or story. The interviewer's talk is to identity she

traumatic references.. These may be obvious or obscure,

bus are invariably present and recognizable.

White telling she story, she child is seen to struggle

witti unacceptable, painful or frightening feelings which

may disguise she traumatic reformco. The drawing and

story provide clues to she sources of she child's anxiety

and means of topmg.

We have found foor common psychologica) methode

in she ereadolescent groep to limit or regulate their and

witkin she first weeks after she evenj, enig in-f, an~tas

shows she child to mitigate painful reality by

imaginatively roversmg she violent oostome. The child

may provide a more acceptable onding. For exampie, one

5-year-uil whus'legei, a stunt man, was fatally shot in a

family feud,f ~uddenly introduced a safety net after a

clown in her story has been maliciously pushed off a high

wire. Another groep of children avoid renvinding

themselves of she event by eitint spontaneous thoutht jor

roetante, an 8year-old failed to mention she prominent

television set he pistod in she picture. When askerf, he

animatedly told of a program in which Bugs Bunny is shot

at bot safely outruns she attacker's bisets. These chiidren

display momentart' interruptions of their fantast'

elaboration in order to avoid associations to she trauma A

third groep cannot at first engage in fantast'. They remain

fixed to she trauma and only draw she aallel scone. They

will without request begin to glee an unemotional '

urnalistic bot incom toto account of she event.. For

instance, one 8-year-old introduced himseif by saying,

"I'm Tommy, my father trilled my mother," A fourth

groep remeins in _________________________ netent

state of anxious arousah-as if to propere for future

i

Y

308

R. S. PYNo08

Jn his story, one child emphasized his lack of

personal security afteer his father's murder. This •

year.old boy told in his story of a kidnapping Erom a

front yard that was once safe to play in. These children wilt

keep themaelven preoccupied witti thoughts of further

harm in lieu of discussing the real event.

S eco n d S tage: Traum a

?

Reisring the Experienee

Emotional Release. The transition in the interview

Erom the child's drawing and story telling to the ex•

putst discussion of the violent event is

a critical moment

for the clinician and child alike. We have found it timely

and practical to link some aspect of the drawing or story

directly to the trauma. For example, we might say: "1'll het

you winti that:" 1) "Your father could have been saved at

the end like the clown," or, ?) "Your babysitter could have

gorten away Erom the man who was about to slab her," or,

3) "By saying what happend over and over again, you

would gel used to it," or, 4) "Your father were stils here to

protect you." What often follows is a profound emotional

outcry Erom the child. vow the child needs to feel the

interviewer's willingness to be a supportive presente and to

protect the child Erom being overwhelmed by the intensity

or prolongation of the emotional release. The interviewer

must be prepared to share in the grief and horror and to

offer the child physical comfort.

Reconstrurtwr:

Catharsis does nor adequately describe the goal of

emotional release. Before the child proceeds to "relive the

experience," he first must attain a state in which he does

nor feel ton threatened by his emotional ren naes, a state

in which he hes the hope, at least, of being able to begin

to tops witti theet. íf this is adequately achieved, the child

will appear ready to provide a vetbal description of the

event. The interviewer can Lk:cn direct the child by

suggesting that "Now is a goud time to teil what happend

and what you saw." The child wilt rensafe the traumatic

milieu through various devices. He may first choose to

reenact in action or draw the violent stens, bat the interviewer must entourage the child to translate the actions

or pictoria! depiction info words. Props-dofs, puppets,

toys, wegpons, etc.-are made available. The child may

herome engrossed in the reenactment play, so that the

interviewer must be witling to participatefor instance,

acting as the assmient, victim, polsre or

rh

the tentral action the child witnessed when h asral

harm was inflicted: the push to the floot, the blow witti

the fist, the piunge witti the knife, the biast of a

AND 8. WFH

paramedic.

The child should then be supported in his focus on,

shotgun, the moment of forced *eiaal penetration. It

may require firm support by the interviewer for the

child to draw the particular moment of violente. Although a marked increase in aniiety may precede the

child's doing so, afterward the child appears

strengthened in his or her mastery of the trauma.

Occasionally, it is nor until thi8 step that the pain of

the reality is experienced. Again, the interviewer may

tactfully facilitate the emotional release by stating, for

instance, "I bet you wiek the gun had been pointed as you

drew it, away from your Eether, so it would have gnoe off

harmlessly."

Perceptual Experiene. We follow this description of the

action by addresaing the child's sensory experience of the

episode: the sight and sound of the gunfire, the screams or

sudden silene of the victim, the first sight of blond, the

splash of blond on the child's own tinthese the death egony

of the victim, and the sirens of the pokte arrival. This recall

cao be elicited by a comment such as "Boy, you must have

gorten blond on you." In several cases we have been

surprised to have the child add that he or she was wearing

the verg pants which had been stained witti blond during

the violent episode. In addition, whenever a child describes

an intense feeling state, we ank him about the concomitant

physical sensation. For example, after a child said "It feit

awful," we asked where he feit it. He replied, "My heart

hart, it was beating so Eest."

Throughout this account of the traumatic event, the

child's selection will be influenced by cognitive development and style, previous history of trauma, violente or

losse and the actual circumstances. The child is also

continually attempting to tops witti the accompanying

affects: helplessness, passivity, fear, rage, roofanion, vilt,

and wen sust ment.

The role of the interviewer is to function as a holding

environment in order to provide a safe and

ro tel setting so that the child can further work at

mastery lespits the rising anxiety level. The interviewer

does nor allow the child to digress Erom this allimportant taak. He may need to question the child to

ensure that the circumstances and aftermath are fully

reviewed. Following completion of the child's account, the

interviewer must be sensitive to how physically

exhausted and emotionally spent the child may be in

contrast to the asaal psychiatrie asanion. Relaxation time

and snacks should be offerel The child needs to feel that

he or she is beig adequately ratel for during this

emotionally challenging time.

Special Detailmg. The child may imbue a particular

detail witti special traumatic meaning (Freud, 1965).

These details are of psychodynamic importante and often

provide clues to the child's initial identification,

309

wITNESS 1'o VIOLENCE: CHILD INTERVIEW

J

, .

for exatnple, with she aggressor, she victim of, Wg may

add, she protector, including she pokte. One adolescent

girl became preoccupied because her mother had been

shot while wasring a drens she daughter had lept she

mother that morning. A 5-year•old dwelled'on whether

his deceased mother's lege were braken, in part because

he had worp leg casts as a toddler and wished to have her

Eiwed up in that way, too. Another boy painfully recalled

having been immediately made to weer she belt used by

his father to beat his mother to death in order to hide she

evidente. White recognizing she unconscious significante

of these details, she immediate goal of she interviewer is

to hel she child distinguish himself from either she victim

or she assailant.

Worst Moment The interviewer cao then proceed to

ank about she worst moment for she child. It may not be

what an adult would asname, nor even something as yes

mentioned. Even young children have sufficient

observing ego to nettact on she avant and then movingly

describe a uniquely painful moment. This may meiode a

memory from eerlier in she day or from she violent

occurrence or from afterward. One 8year-old broke down

in teers as he told of she moment when he found a razor

blade ander his suicidal mother's bleeding arm. He had

been sent out that day to boy she razor blades, he

thought, to make paper meeha objects. He cried in total

disillusionment. One 7•year-old girl painfully netstad that

her father had celled out her nickname as he died from a

gunshot wound. A 14-year-old girl described a moment of

intolerable anger when in passing her father at she pokte

station he leid, "I'm sorry," having jast shotgunned her

mother to death. A 5-year•old expresled his int

dssappo.ntme..Y vhMt on rhr..rvmas E...+n Claus had

not arrived bat a bad man, a killer, instead. This exchange

is a particularly empathie rooment for she child as he feels

especially understood and close to she interviewer.

Violente/Physk& Mutilation. The interviewer must

now be witling to guide she child to approach she impact

of she violente and physical mutilation. Children may be

haunted by an unforgettable visaal image and may

struggle to unburden themselves of she light. Certain

children may insist on drawing a picture of she mutilated

or wounded panent. Other children may be more

reluctant, bat witli proper support wilt draw she

horrifying and painful light.

We have been impressed witli she child's naad to

nastore an image of she panent as physically intact or

undamaged. In cases of perental death, she funeral offers

an opportunity to view she panent as once again

nastond. Inquiries about skin ceremony are especially

fruitfut. We wilt allo ank if she children have a pho

tograph of thee paraos and, if one ia available, are wilt

look at it witli tbe child during she interview. In addition

to eiding she grief proces, this step helpe she child to

invoke eerlier, kappier images of she panent to counteract

{.Ili7b

she more recent, gruesome light. Hoorever, she validation

of eiternal reality and physical death or injury nawis to be

confirmed and, especially, for she younger child to be

concretely represented in play or drawing. Only when

children are secure in she belief of their perent's pbysical

death have we neen children speek openly of their grief

(Furman,1974).

Coping witli she Ezperience

Issues of Hwnan Accouritability. These are acts of

human violente, not of naturel disasters. Struggles 'over

human accountability add considerably to she child's

difficulty in achieving mastery. As recognized witli adults,

,posttraumatic stress disorder ia made more lavare and

longar lassing when she stressor is of human design,

especially human-induced violente ( DMS-III; Frederick,

1980; West and Coburn, 1984). As one 12-year-old leid,

"I'm mad at she way she did go. Beaune that hart. I jast

wanted her to die naturally, not die because someone shot

her.„ The child must confront his awareness and conflicts

over who is responsible. He may wish at first to avoid she

issue by telling she avant an accident, bat this provides

only superficial relief.

The interviewer ezplores she issue of whom she child

holds accountable for she act, his own onderstanding Qf

she motive, and she trild's conjecture about ways it could

have been prevented. For example, we ank "Hoor coma

it happened?" And then, "What would make someone do

something like that?" 1f she assailant is a strenger, it may

be easy for she child to assige .~e diama. Huwever, f& iiiy

ViOiel ;e cao throw she chlld info an intense conflict of

loyalty and he may suppress certain thoughts as

unacceptable to other family membars. The child might

have already ezpressed his view

in she story telling. A •y

7

h e r

f a t he r

m o t h e r

f a t h e r

e v il

as

h e

f r o m

a t

b oy s

s c u f fl e d

f ur t h er

f a al t .

w h o

wi t li

p h y si c al

H o o r ev e r ,

i n

u n e x h e c te d ly

h e r

cl e ar ly

mi sl e d

h e r

f a t he r

n ei t h er

c o ul d

s h e

a c cu s e

d u ri n g

s h e

m e n t

s h e

t ou rl a

t h o u g ht s

m o t h e r

f o r

a s s i

ab o u t

w o ul d

b e

o f

sh e

s o

t w o

a n d

h er

s aw

h er

b r o t h er s ,

Ev er y o ne

s t or y ,

a p p ea r

b a t

T h e

h er

a sa al t .

S h e

r e s p o ns i bl e

e a r - ol d

a n d

t h i s

a r e

w ould

w h o

e l s e

c hi l d

i n t en s

n o t

m o th e r .

a d d

S o

m o t h er

s p o o t

w er e

h el d

a s s i g n ed

o n

t o

b l a me

t o

h e r

si le n t ly

p r o f e et

a bu s iv e ,

ma n d e m o n

Ma n n a

s h e

t ryi n g

s h e

t o

s he

a lc o h o l cc

t w o

y ou n g ,

t r ou bl e m a ki ng .

m e m o ry

h el d

h er

o f

ki m,

b r ot h e rs

d ea t h .

r e sp o n s ib il it y

o f

s h e

is

n o t

i n t erv ie w .

v ic t i m 's

p r ov o ca tiv e

a c ti o n s ,

as

a lw ay s

T h e

f o r

c h i ld

f i x e d

a nd

m a b e

n e e n

m a y

b e

m o s t

c o n t a nt e ,

in

w o n de r mg

t o

v ar y

d i st ur b e d

w hy

by

s h e

310

R. S. PYN009 AND S. E'TH

to have yelled at her eeltangel busband the following: eipression of these particular fantasies may provide

"Go abeel, shopt me. Show the kilo what a big man you enough emotional relief that certain children, who had

been teloctant to describe the mutilation, wilt now do so.

are."

One 8-year-old boy enacted a sequence in which he

Innen Plans o/ action. We have been particularly

imagined his Eether ia taken by ambulance to the

hospital, operatel on, the ballet removed, and the wound

impressed by she children's immediate efforts to te

verse their hel lessnees b formulatin a lan of action

that wound have remedied the situatien., Liften (1979) tien

referred to these cognitive reeppraisals after catastrophic loss of life as "inner plans of action" and

suggests they are repeatedly asel to contentwith the

Jdeath imprint." As we have observed, the inner plans of

action may soek to alter the precipitating events, to

undo the violent act, to naverso the lethal conse,quences,

or to gein safe retaliation. Their content and time frame

are developmentally influenced (Eth and Py noes, 1984).

Because of their limited cognitive skilis, the prel

school children do net appear to imagine alternate

actions they might have taken on their own t.o erevent or

alter the episode.,It is they, therefore, who faal the most

heiplas. They may choose to flee or stat', look or turn

away, be attentive, or try to sleep, bul all of these are the

choices of a passiva witnes, net a participant. The

ereschool chiid may fantasize about potsilo help having

provided needed third party intervention, and, in his play,

look to the interviewer to fi11 this role.

In contrast, school age children do net act as mare

witnessen. They can participate, if only in fantast'. They

can imagine having celled the police, lockin vh doorn,

grabbing a wegpon away from

assailant,

mother's lege ware braken also had the opportunity to

ank a doctor for help loting his story play. Witti the

interviewer's aid, he then fixed up the braken logs of

aid to the victim. Not ismgly, these innereven

plans

capturing the

of action are n

always confined to assmient,

the day ofrein

the

y o ering

ava nt. rFor e xam pie, witti toe intervicwcr

p!aying the

role of the assmient, ene 10-year-old boy acted out how

he imagined surprising the manlener, kicking the gun oi".

of his hand, and lossing it to his unarmed Eether.

Adolescente can imagine alternativo actions over a

mach longen eerled of time. They do net merely fan

tasize participation, bot can implicate their own action or

inaction in a more realistic fashion. One 14-yearold

bitterly regretted her Peilure to ampel her father's gun

when she had had the chance 2 weeks before. A 1?year-old boy, in trying to stop the tape of bis

mother, was overpowered by the assailant in a hand to-

hand knife fight, and, afterward, continued to imagine

ways he could kill the man if he ever faced him again.

Especially important are ways the chiid imagines the

panent could have been "fixed up" or aided, _ the injuries

ware sustained. For example, the young boy who was

concernel witti the thought that his

his fictional injured race can driver. Furtherrnore,

stitched closed. Witti encouragement, he then readily draw

the view of the bloeding chest wound that continuel to

intrude on his mind.

We carefiiily explore all these cognitive reappraisals

(Folkman and Lazarus, 1984) for they are the best

i,ndication of the wars the chiid is troubled by feelings of

self-blame for net doing more. Enactment of these "inner

plans of action„ can offset lingering feelings of personal

responsibility.

Punishment or Retaliation. This discusion of blame can

raise the question of punishment or retaliation. It may

prove diff colt for the chiid because it can reveal

unbearable Peelings of Built in neme children and

frightening fantasies or dreams of reven ge in ethers. In

part, these Peelings serve to counter the true helplessness

at the moment of the violent act. We wilt allow the

children to Biva Eidl expresion to these , Peelings

_______________ remindias theet of the realistic limitations

to w t tinut couId have doge at the time. , The children

effen look relieved by permission to imagine the tortures,

multilations, or execution they have reserveti for the

assmient, and readily draw a picture of "What you'd like to

nee happen to him." Afterward we will raspond, "I nee it

Pools goud to imagine Batting back át the had man who

stabbed your father," adding "1 meen, to be able to do

something to him now, when you really couldn't have

stoppel him at the time."

Counterretaliation. Themea of nevengo may be associated witti fears of counterretaliation by the eengilent.

The chiid may be afteil of the assailant's return and

confused over what hes actually happened to the suspect.

If the assmient is already arrested, the chiid may be

fearful over the fotore release of the suspect. We are

concernel about how rarely the chiid is raassured about

these matters by the police or the local district attorney.

Child's Impulae Control If the chiid attributen the

assailant's action to enger, bate, rejection, om craziness,

etc., it is pertinent to ank, for example, 'What do you do

when you Bet angry?„ and to ex lore the challenge to the

child's own impulse control. Viewing an open display of

violence may net only causa the chiid to ipso trust in adult

restraint, bot he or she may acutely foet his or her own

capability, especially in

Í

WITNESS To VIOLENCE: CHILD INTERVIEW

Light of coneciouz revenge fantasie, and be concernel

about the lack of proper eiternal support.

Previous Trauma. After this discusion, it ie comInon

for a child spontaneoualy to menden pestlno • etstic

experiences. We have leernel from children of further

inlaates of child abuse, violent family deelha, unreported

suicidal behavior, physical injuries, or accidenta.

Traumata Dreams. At this point, we inquire about

recent dreams that may be remembered. Often a child

sepotla anxiety dreams directly teleled to the traumatic

event. The child may be fearful that the dream

representa a portent of the fotore, nol only of being

victim of a violent aasaalt, bot sometimes betoming an

evengrog killer, toe.,

Foton Orientation. It is now appropriate to aak the

child about his or her concerns for the fotore, specifically as they relate to the potential langers in interpersonal relationships. The child may have immediately

after the trauma crystallized a _v_ivid and re-, ~tricted

view of his or her own fotore. One child described how

when he grows up he intends to live in an unaccessible

fortress surrounded by many gaard logs. Mant' children

slatel that they never latend to many or have children

for fear of a similar violent outcome. Even school age

children sometimes described changes in career plans

for when they got eides. For example, one 7-year-old,

withm days of her father's killing, sepottel she suddenly

decidel on a new life ambition, to become a stand-up

comic who dressed in tags and made ethers laugh.

Similarly, the child feels burdened witti an awareness

of his or her unfortunate legact'. Children will complain

about the novelty and stigma of being the heit of a patent

who lied by murder or suicide. For lastante, one 11-yearold girl bitterly lamented her face as a laagtiter of a

'man who barnel himself to death.'

Current Stresses. When sufficient mastery of the

traumatic anxiety hes been achieved, the child can more

actively address the life stresses engendered as a

consequente of the treurneut avant. He or she may

spontaneously and pointedly inquire about placement or

schoolmg, or be easily encouraged to do so.

We survey a number of the temmen, easily overlooked

issues that may add to the child's distraas. These rotlade

tentacts witti the pokte and legel system, changes in living

situatien or schoeiing, awareness of media coverage, and

concerns about social, sti sta. We offer to help redres any

oversights in the child's care. For example, in gelag to stat'

witti her grandparents after her mother's laatdar, a 14year-old had to abruptly change schools and lost the

companionship of her established tinla of friends. We ware

311

able to asrange to have her old friends visit her at her new home.

Exploration of these poettraumatic consequences enables the child

to consider the impact of the event on hie tomaat life

circumatances.

Third Stage: Closure

Recapitulation. The sensitive pretera of terminalmg the

interview is now begon. The first step is to elicit the child's

cooperation in re ' and summarizing the wasion. We

attempt tó make t e child's responses weet more acceptable

by emphasizing how onderstandable, realistic, and

universal they are. By doing so, we also hope to have the

child feel leas alen and alienated, and more ready to

receive further support from ethers. The interviewer

returns to the initial drawing and story.. The link to the

trauma may be more clearly indicated perhaps by pointing

out a similarity to the child's later reenactment or

recounting.

Resustic Fears. It is important to repeat that it is all ri t

to have feit helpless or afteil at the time and then rad or

angry. We also make reference to what ether children

have teil us , after being in similar circumstances. The

threat to the patent is so overwhelming at the time of the

violente that many drildren do nol entertain a realistic

appraisal of their own personal jeopardy. Afterward, they

may ignore, leave unacknowledged, or suppress any fear

they might have experienced for their own safety. In one

case, we could point out how far away from the shooting

the child piscel himself in his drawing when in fact he

was so close as to have easily been shot himself. This

intervennen alleviated rather than aggravated the child's

anziety, perhaps by unburdening the child of the need to

suppress his fears.

Ezpectable Course. We share witti the children the

expecteble tourre, for theet as they pass through the

tourre of their traumatic netflens. For ezample, we might

say, "There grill be timer at school when you think about

year mom, and faal rad." Or, 'You may faal frightened to

ree a knife at home.' Or, "You may jump at the sound of a

lood noire," or "You may have some bad dreams bot they'll

happen leas and leas witti time." We suggest they share

these restbons witti trustel adults to gein further

assistante at these ditficult moments.

Child's Courage. The child's beleaguered self-asteem

nawis support. We may be able to acknowledge the child's

bravery. For instance, in one case a 5-year-old stamparel

out a window and down a fire escape to reek help for her

woonled mother. Qne convenient method is to retlect on

the child's performance dunne , the interview, net only

telling him what a goed job he lid bot, more important,

complimenting him on his courage to engage in rotti

difficult talk. We will ac-

312

a. S. PYN008 AND 9. frH

tualy say, "You are verg brave." Children invariably

grew for me and my eister and cut info the ehape of a

tien and a hippe. Fm going to etska aura to keep

swell witti prils upon hearing these word.

watering theet.

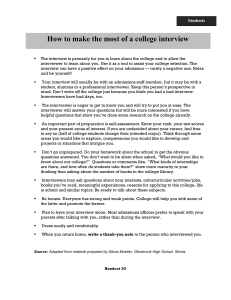

Child's Critique. The child is then askerf to describe wbat

bas been helpfui or disturbing about the inter• view. The

Consultant (C) : This ia the kind of Story you weidl

children are usually quite candid. They wilt describe what have likel to have happen instead of what lid.

issue had been "toughest" to talk about, what had been

Lisa: Yes (she begin to cry and is comforted by the

unhelpful, and what made theet faal tetter. In fact, they interviewer). She had jast been offerel a job a couple of

have been our best teachers. Before we understood days hefere the accident happend. She never had a

the rota of suppressed fear, ons child turnerf to ons of chance to take it. We could then have afforded to move.

us and eiclaimed, Boy, was it goud to say how afraid I Now she's moved to heaven and we're going to have to

was."

move somewhere eire (she continues to cry and accepts

Lesas-takin . As we end the interview, we glve expresion

physical consolation).

of our respect for the child and the privilege of haaing

C: i know it's going to maks you rad to talk about soms

shared the interview experience witti hun. We then of this.

emphasize our availability to be celled on in the future.

Lisa:1 don't care.

We generaily give the child, tinwever young, our

C: Maybe this is a goud time to teil what happend (she

professional card witti our telephone naether. It is then begins to describe the actual murder scans and was

important to issue open the opportunity for contact, as encouraged to draw a picture of it (Fig. 2)).

effen the trauma wilt be reactivated-on its anniversarv

Lisa: This is my mother handled up on the coach.

date, for instance. At such timer mant' chiln dren have She's jast waking up. The man is right here, talking in

sought us out lespita the brevity of this initial front of her face. At first I was jast taking a nap and the

contact. In these cases where the child hes been referred

baby was jast in tlie bedroom. When I came out and save

for further treatment we have observed that this hun witti the gun I was so scared, t jast stond there

consultation witti proper closure hes facilitated the looking. He was flicking the gun in her face. He then

child's adaptation to the treatrnent situatien.

shot her. He kapt shooting her until he got to the door,

and then he ren out somewhere.

Case Illustration

I waited until I haard our screen door shut, `causa I

Lisa, who is 11 years old, was interviewed 5 days

didn't

want to gat shot. Then I ren up to my mother, who

after her mother had been fatally shot by the rnother's

was

rolling

off the coach and she feil on her aide. I rolled

estranged boyfriend, .Jim. On the day of the murder Lisa

her

over

and

was talking to her. I was crying and I was

and her mother veere at home babysitting for a neighbor's

mal

because

I didn't know what to do. I grabbel the

infant, white Lisa's younger sister was at school. When

phone

to

call

the police bat I think they'd already been

interviewed, Lisa and her sister veere temporarily residing

celled

by

the

neighbors.

Before the police came I was on

witti a cousin and her young children.

the

floer

witti

her.

Her

eyes veere down, her evelids

The consultant began the interview by inviting Lisa to

veere like half-closed, and her hair was kind of messed

draw a picture and maks up a story stout it (Fig. 1).

L..: We weke up in the morning and we veere up, sticking out. B1ood was everywhere. I was trying to

packing. Then we gat info our car and the moving open her eyes. I Was trying to wake her up-you know, by

truck. We're losding everything onto the truck and we're shaking her face. I thought maybe if I lid something

moving so that if Jim came back he wouldn't find us, so wrong she weidl do something. 1 trial to listen to her

he can't sheet my mother. That's my mother who is haart and to take her pairs. 1 couldn't find anything. I'd

moving the plant. My sister is watering the gras and reen that on a soap opera 1 watehed witti my mother

When somebody got shot. Also, you know how when

I'rn heiping to take the planfa off the porch. And

you can't breathe how you pres their stomach or

everyone is feeling happy.

something, I Was trying to do that so she could breathe,

My mother lover plants. She had house planfa and all

kinds of planfa. I don't really know the name of theet bat bat she wasn't breathing right, and when she look a

she had locs of planfa around the house. She look goed breath thee blond startel to coma onto the goor. I kegt

care of theet. She didn't really like us heiping witti talking to her bot she wouldn't talk. 1 thought if only she

the plants because we might do something wrong and could talk then everything could be all right. I jast look

they might die. She wanled to take care of theet her hand in mine, and kegt shaking it white telling her to

bang on. I was crying and 1 askerf God to save my

herself.

Mommy and I'd be a goed girl, bot he look her (Fig. 3).

Right afterward the plants veere all given to

ARerward i went and teckel all the doors.

neighbors ezcept two. These veere ones Mother

C: You tried your best to help her if you could. I'm

especially

313

wrrNESS 1'0 VIOLEHC& CHILD INTERVIEW

1

3

J

5

r

r

I

3/

r

r

FIGS. 1-5.

Patient's drawinp of traumatic event.

sure you couldn't stop the bleeding. You worry you

could have dove more.

Lisa: There was ton mach blond

C: Did you get blond on you, ton?

Lisa: It was on these pants. These veere the pants I was

weermg. gut they've been washel 1 guess I had some

right here `causa I was listening to her haart. Her shirt was

Eidl of blond, and when she trial to breathe she made a

sound like this (she inhaler in a gasping menner) and

she lid it for a long time. Sometimer I remamber how

the gun sounded, how lood it was.

C: It's really something to go through.

Lisa:1 am not really mad at the fact that she's deed

because you know everybody bas to go, bot 1 am mal at

the way she lid go. Because that hort. I jast wantel her

to die naturally, not to die of a shooting or stabbing or

strangling or something like that.

It juat doesn't faal right. Oh, how she lied. Like that,

horrible. She should have lied naturel, and maybe I

could have been groven because that way I wouldn't have

lost a mother truly. I was scared when the police came

because first they knocked on the door real lood But I save

the Eire truck and it had a eiren on. So I knew it was the

polka. They didn't beige in as I thought they might

have. when the polka came I wantel to stay with my

mother bot they moved me to the next room for awhile.

314

R. S PYHo08 AND $. ITH

u$ to do things their way. It'i kind of hard for ua becauae we jast loet a

Tbat's bad that hei reet been found yet. I vees

thinking tbat my mother would be looking for kim and

teil me, $o then I could telt the police and they'd Eind

kim (she draws her mother in heaven (Fig. 4)).

She is in heaven witti God. He kas long halt. Jesus

had long halt. She's looking down on us. When she

neen us cry she vries toe. Shell maks sure we've all lelt so if

.lira vemen back he'll have a big surprise because nobody

will be there.

C: Do you get scared?

Lisa: i got scared this morning. I didn't want to go

outside because Jim could be somewhere outside. I askerf

my uncie to gel kis gun and scans away the man i save

across the streef. Maybe we could catch Jim, gel kim to

drop kis gun and bring kim to the police station.

C: You valled it are accident, net murder.

Lisa: ,lust a name I picked for it. But a man really dia it.

Marden sounds like when somebody chokes or strangles

somebody. I guess I'd say he killed her because that

doesn't meen so much physical contact. Mavbe if I

haarei weke up she wouldn't be dead. He probably got

scared when 1 save kim witti the gun.

C: And he dia something terrible to your mother.

What maken a person do something like that?

Lisa: I guess hete and enger. He wasrei out friend and

she tolel kim she diarei want to nee kim. I guess he got

angry at that.

C: What would you like to nee happen to kim?

Lisa: I was dreaming that all my cousins and out

relatiees veere dressed, you known, how they put you up

against the Wall and blindfold you and sheet you. i had

the name knife he used to slab my mother and the

name gun that he shot her witti. Then i went up to kim

and raid, 'Do you remember this, now you care feel it.' And

i stabbed kim rght where he stabbed my mother. Then 1

nala, "1 guess you remember this, toe,' and then 1 shot

kim. Then 1 meeerf, and evenbody starterf 3hooting kim

(she comments on how goed a pic.ure that is to draw Fig.

5I ). It feit goud like I was getting back at kim. The hands

are hekma kis back. He's lied up and the scarf is

around kis neck because we look it off so he could nee

what kappens.

C: Do you know what will happen if he's arrested?

Lisa: Heil go to jail. But I want kim to stat' in jail for

the rest of kis life, since he look a life from somebody he

ought to gel kis life down to nothing.

C: There must be timen when you gel angry at

somebody.

Lisa: When 1 gel angry 1 don't like to show my

Peelings. I jast keep them in. I held my breath and jast

don't think about it. But since my mother's death I can't

really control it all because the way people treat us it

seems like it's all out faalt she was dead The way

they're telling us to change so quickly. They want

mother. He must have had a hot temper. When t gel maa at my eister

now 1 gel afraid i might hit or hart her. I don't like that.

C: Do you ever think about her relationship witti men

and what it will be like for you when you gel eiast?

Lisa: 1 nala I'd never gel maaierf and have kils, cauee if

me and kim light, something might happen to me where I

have to die. Then I will leave my klas jast like my mother

had to issue. And I don't want to do that to my kids.1 had

that thought the naroe day she died. I was thinking about

when I have groven kils she'll never be able to nee her

grandkids in person.

(Toward the end of the interview Lisa began to address

neme of her current concerns.) We might have to go to are

orphanage. I don't want to. Nobody is there like relatiees

or anything. One nessen I don't want to go to a losten

home is because they might separate me and my sister.

It's bad enough we lost out mother.

C: Remember you tolel me how veeli your mother looked

after her plants. I think you want somebody to look after

you witti that much care. You must feel that God is being

very unkind in letting this kind of thing happen in your

life.

Lisa: Yeah. That sure isn't fair because I understand He

wanled her to issue us in this way bul why dia it have to

happen? Or, the least He could have dove was walt until a

verlam age when we could have been on out oven.

C: How kas it been to talk witti me?

Lisa: It made me feel hart and stuff, bul it also made me

feel goed.

Overview

We have described a complete interview fermst designerf

to assist children who have witnessed a violent act. The

heiplens, passies experience of watching the moment or

moments of a violent act and lts injurious consequences

constitutes are immediate psychic trauma for the child

(Pynooe and Eth,1985). The eiswing is painful, frightening,

and distressing. Our werk bas been witti the moet

traumatic cases: a perent's suicide, murder, or raps (Eth

and Pynooe, 1983; Pynoos and Eth,1985; Pynoos et al.,

1981). We think the "hammen effect of examining

catastrophic violence kas brought to light more visibly the

processen needed to werk witti children in mant' ether

clinical settings.

Although the technique we have described mat' appear

rigidly structureel, in fact, the sessions generally fellow

the child's leed and are rarely experienced as

,

315

childhood was written by Levy (1938). "Release therapy"

was specirically devised as a paychotherapeutic technique

to resolve symptoma arising trom a "definitely koewo

traumatic episode." The child's traumatic anxieties,

especially these related to aggressive behaviors inhibited

by fear veere discharged through directed play. Levy's

technique hes net received further exploration, in part

WITNE99 To VIOLENCE: CHILO INTERv1EW

`rbitrary or stifling. It would neem that there is an

underlying logic to the interview procesding in this way.

We have been impressed that neme child psychietrists

intuitively eenduet their initial interviews witti

traumatized children in exactly this way without consciously recognizing the unique (ormat. Most ether

clinicians wilt miss the child's cues and lens the opportunity for ready exploration of the traumatic mat2rial.

There have been occasions where we have tac• itly

colluded witti the child's avoidance and omitted soms

component of the interview, only to team afterward that

incomplete masterg of the trauma•related ansiety had

been achieved. We caution child therapists who teel

inclined to avoid the traumatic material to be aware of

countertransference identification witti

the affected child.

Particular attention must be paid to the tinel phase )f

the interview as incomplete closure threatens the

effectiveness of the session. Without proper closure the

child will be left struggling witti traumatic material

without adequate enhancement of ego Eenellen witti

which to bind his anxiety. In that situatien, the interview can be experienced as unsettling.

This technique hes been readily learned by a number

of child therapists and applied to their werk witti a variety

of traumatized children. We have noted that neme of our

tolleagues have voleed concern that the interview's focus

on the traumatic event could unduly upset an already

victimized child. Our extensive experience, supported by

the werk of several ether investigators ~ Ayalon, 1983;

Frederick, 1985) confirms that open discussion of the

trauma offers immediate relief and net further distrens

to the child. Recent adult investigators have suggested

that there mag be an optimum time to provide intervention

bevond which it is more difficult to achieve ego

restoration and improved affective tolerante ( Horowitz

and Kaltreider, 1979; Van Der Kolk and Ducey, 1984).

Chcldhood Trauma

because of its limited scope.

A nalogees .Model

In searching for an analogous model of therapeutic

trauma consultation, we have been impressed witti the

resemblance hefwem our technique and that adopted by

military psychiatrista for the treatment of eelthere who

have viswed a buddy trilled or maimed in combat (Fox,

1974; Glans, 1947, 1954; Grinker and Spiegel, 1943;

Hendin et al., 1981; Kardiner, 1941; Kolb and

Mutaiipassi,1982; Lifton,1982; Smith, 1982; Teicher,

1953: U.S. Public Health Service, 1943). The principles

we share include: 1) the witnessing of extreme violente

constitutes a unique, severe, psychic trauma; 2) the

importante

of

"front•line

intervention"

hefere

maladaptive ego resolution is organized; 3) einee "ego

contraction" is a primary consequente of the trauma,

major efforts are directed at ego restitution and toplog

enhancement; 4) mastery required an affectively experienced "reliving," including a comprehensive review

of the traumatic event; 5) aggressive themes, especially

of retaliation, threaten ego restoration and must be fully

explored; 6) an "outraged superego" responds to the

passivity of the trauma experience by insisting that more

should have been dove to save the victim, and its

demands must be relived by the interview; 7) absent or

pathologie grief results trom efforts

to

avoid re-evokine trauma ic' anxietv', and 8) sus. .

________________________________

tained mastery can only be achieved through reinte

ration info the groep, family, or eommunity.

Similar interview methode fellow Erom these printiples. We remaio heiibis: at timer insisting the child

continue, at ether timer participating theatrically in

the reliving of the episode, and occasionally

asneming the cols of an interestel bystander.

Whenever stifled grief emerges, we offer open

consolation and physical comfort. We underscore

the realistic teers associated witti a langer, and

normalize the aniiety in reexperienting the event in

session. However, the two techniques differ in

handling the opening phase of the interview. Since

eelthere display traumatic amnesie or disavowal,

narcosynthesis or hypnosis veere often net•

Recent reviews have discuseed the significant psychologica) impact for children of a velde variety of

traumatic experiences (Eth and Pynoos, 1985; Ten,

1984). There is tetter recognitien of the intrapsychic,

behavioral and physiologic changes that can otter.

There mag be prominent intrusive and avoidant phenomenon, increased stater of arousal and incident speeltic

new behaviors. Reporta of longterm effecta have included

pessimistic life attitudes, alterations in personality,

diminished self-esteem and disturbances in interpersonal

relationsbips. Because these treematic sequelae do net

necessarily pass witti time, there is an obvious need to

develop effective methode of early intervention.

The landmark paper on the treatment of trauma in

essary adjuncta to penetrating these lefmees. On the

ether hand, we have found that children remaio consciously aware of the traumatic event, though

'nishing its pain through the ure of lens)-in•fantasy or

,

avoidance.