bells - Extras Springer

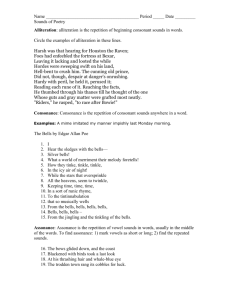

advertisement