chapter web sites

advertisement

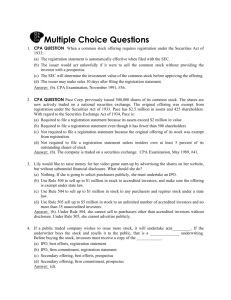

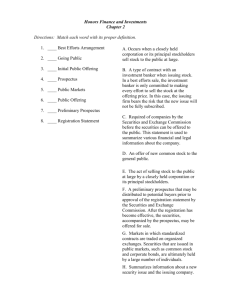

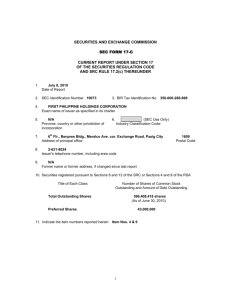

Chapter 16 RAISING CAPITAL SLIDES 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 16.8 16.9 16.10 16.11 16.12 16.13 16.14 16.15 16.16 16.17 16.18 16.19 16.20 16.21 16.22 16.23 16.24 16.25 Key Concepts and Skills Chapter Outline Venture Capital Choosing a Venture Capitalist Selling Securities to the Public Table 16.1 - I Table 16.1 - II Underwriters Firm Commitment Underwriting Best Efforts Underwriting Green Shoes and Lockups IPO Underpricing Figure 16.2 Figure 16.3 Work the Web Example New Equity Issues and Price Issuance Costs Rights Offerings: Basic Concepts The Value of a Right Rights Offering Example More on Rights Offerings Dilution Types of Long-term Debt Shelf Registration Quick Quiz CHAPTER WEB SITES Section 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.10 Web Address www.vfinance.com www.dealflow.com www.globaltechnoscan.com www.pwcmoneytree.com cbs.marketwatch.com www.ipo.com www.ipohome.com www.hoovers.com www.ml.com www.bloomberg.com www.dallasfed.org/htm/pubs/er.html A-208 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER ORGANIZATION 16.1 The Financing Life Cycle of a Firm: Early Stage Financing and Venture Capital Venture Capital Some Venture Capital Realities Choosing a Venture Capitalist 16.2 Selling Securities to the Public: The Basic Procedure 16.3 Alternative Issue Methods 16.4 Underwriters Choosing an Underwriter Types of Underwriting The Aftermarket The Green Shoe Provision Lockup Agreements 16.5 IPOs and Underpricing Underpricing: The 1999-2000 Experience Evidence on Underpricing Why Does Underpricing Exist? 16.6 New Equity Sales and The Value of the Firm 16.7 The Costs of Issuing Securities The Costs of Selling Stock to the Public The Costs of Going Public: The Case of Multicom 16.8 Rights The Mechanics of a Rights Offering Number of Rights Needed to Purchase a Share The Value of a Right Ex Rights The Underwriting Arrangements Rights Offers: The Case of Time-Warner Effects on Shareholders The Rights Offering Puzzle 16.9 Dilution Dilution of Proportionate Ownership Dilution of Value: Book versus Market Values 16.10 Issuing Long-Term Debt CHAPTER 16 A-209 16.11 Shelf Registration 16.12 Summary and Conclusions ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE Slide 16.1 Slide 16.2 Key Concepts and Skills Chapter Outline 16.1. The Financing Life Cycle of a Firm: Early-Stage Financing and Venture Capital A. Venture Capital Venture capital – financing for new, often high-risk businesses First-stage financing – early financing used to get the firm off the ground Second-stage financing – subsequent financing to begin operations and manufacturing Slide 16.3 Venture Capital Click on the web surfer icon to go to the PWC Money Tree report. Real-World Tip, page 526: In a Forbes article, Guy Kawaski, business author and CEO of Garage.com, a start-up capital firm, identified four factors that investors should consider. “Factor number one: the idea … ask who would use the product. The best answer is that you already use it. The second best answer is that you would use it if it existed.” He also suggests that the business model should be coherent and that development of the firm can be broken into stages. “Factor number two: the source of the referral. The best source of investment opportunities is people who have experience picking from a constant flow of new deals.” “Factor number three: the quality of the entrepreneur. You want to invest in people who run at a high-megahertz rate … and who are adaptable.” “Factor number four: the existence of organizations that would be natural partners and allies … today’s partner is tomorrow’s acquirer. It’s nice to have an exit ramp.” Real World Tip, page 526: Information on venture capital is much more readily available than it has been in the past. The introduction of publications such as Red Herring and Wired has provided substantial information on high-tech firms that have not A-210 CHAPTER 16 yet gone public. Red Herring regularly profiles firms in columns with titles such as “IPO Candidates” (private companies projected to go public within the next six months). The Internet is a bountiful source of information on venture capital and high-tech startups. In December 2001, entering the keywords “venture capital” into the AltaVista search engine resulted in 1,189,228 hits, up from 528,706 in October 2000! Real-World Tip, page 527: Various groups supply venture capital. An article in the May 16, 2000 issue of Inc. magazine discusses Champion Ventures, a venture capital firm based in California. It’s first fund was for $40 million and included investors such as Barry Bonds, Wayne Gretzky, Joe Montana, Dan Marino and others. Corporations are also getting into the venture capital game, although they often refer to it as “strategic investment.” One such company is Intel, who formed its venture capital program, “Intel Capital,” in the early 1990s. It was originally designed to provide funding for companies that would complement its product line and capacity. It now invests in a wide range of companies including Internet companies and companies that are trying to expand bandwidth for users. Real World Tip, page 527: PriceWaterhouseCoopers Money Tree Report provides information about VC funding on a quarterly basis. Go to www.pwcmoneytree.com to investigate current VC activity by quantity, sector and region (the hot link on Slide16.3 will help). B. Some Venture Capital Realities Even with the explosion in VC funds, access to venture capital is still limited and expensive, particularly when you consider that VCs often take large equity stakes in the new firm and may exert substantial pressure on management to do things the way the VC wants. On the other hand, small, risky firms might never be able to get off the ground without venture capitalists, which would deprive society of much of the innovation we have enjoyed in recent years. C. Choosing a Venture Capitalist A list of important considerations when choosing a VC is provided below: CHAPTER 16 A-211 -Financial strength – you want to make sure the VC will be able to provide additional financing when necessary. -Style – since VCs often take an active role in advising management, you want to make sure that your management style is compatible with the VCs style. -References – you need to obtain and check references. Has the VC been successful in other ventures and how have they handled adversity. -Contacts – ideally your VC will have contacts that will be useful in your business. -Exit strategy – VCs are not long-term investors. How does the VC anticipate getting their investment back from the business? Slide 16.4 Choosing a Venture Capitalist Click on the web surfer to go to www.dealflow.com. 16.2. Selling Securities to the Public: The Basic Procedure Process for issuing securities: -Obtain approval from the Board of Directors -File registration statement with SEC -SEC requires a 20-day waiting period Company distributes a preliminary prospectus called a red herring Cannot sell securities during waiting period -The price is set when the registration becomes effective and the securities can be sold Tombstones – large advertisements used by underwriters to let investors know that new securities are coming to market Slide 16.5 Selling Securities to the Public Real-World Tip, page 528: The June 2000 issue of Red Herring provides a summary of the IPO process in “The Anatomy of an IPO” (p. 392). It provides a look at how a company goes public starting with choosing the underwriter all the way through the first day of trading. The process is a hectic one with a lot of paperwork and marketing. Video Note: “Going Public” shows what must be done to take a company public. This is a common exit strategy for VCs. A-212 CHAPTER 16 16.3. Alternative Issue Methods -General cash offer – securities offered for sale to the general public on a cash basis -Rights offer – public issue in which securities are first offered to existing shareholders on a pro rata basis -Initial Public Offering (IPO) – a company’s first equity issue made available to the public -Seasoned equity offering – a new equity issue of securities by a company that has previously issued securities to the public Slide 16.6 Slide 16.7 16.4. Table 16.1 – I Table 16.1 - II Underwriters Underwriters are investment firms that act as intermediaries between the issuer and the public. Some of the services provided by underwriters include: -Type of security to issue -Method used to issue the securities -Pricing of the securities -Selling the securities -In the case of an IPO, stabilizing the price in the aftermarket Syndicates – a group of underwriters that work together to market the securities and share the risk, managed by a lead underwriter Spread – the difference between the underwriter’s buying price and the offering price; it is the underwriter’s main source of compensation and for IPO’s in the range of $20 to $80 million the spread is typically 7% Lecture Tip, page 531: The underwriter’s spread is defined as the difference between price and the price at which the underwriter purchases the securities from the issuing firm. In a study of utility stock issues by Bhagat and Frost, published in the Journal of Financial Economics in 1986, average spreads were found to be lower for competitive issues (3.1%) than for negotiated issues (3.9%); however, negotiated offerings are still more common. Chen and Ritter in the June 2000 issue of The Journal of Finance looked at spreads for IPOs. They found that the spread for over 90% of the issues in the $20 to $80 million range was 7%, which is above a competitive price. However, they suggest that this persists because issuing companies are more concerned about the reputation of the underwriter and view a lower price as a signal of lower quality. Slide 16.8 Underwriters CHAPTER 16 A-213 A. Choosing an Underwriter Competitive offer basis – taking the underwriter that bids the most for the securities Negotiated offer basis – the more common (and expensive) method Real-World Tip, page 532: “Corporate America is turning more fickle in choosing finance partners on Wall Street …[m]ore companies are ditching the Wall Street underwriters they had selected for initial public offerings and picking different investment banks when it comes time to complete follow-on stock sales.” So read the opening lines of an article in the December 19, 1996 issue of The Wall Street Journal. But why is this occurring? According to the article, the phenomenon is attributable in part to the fact that many recent offerings have quickly risen above the offering price, leading issuers to feel that their shares were underpriced (and that they left millions of dollars “on the table” as a result). B. Types of Underwriting Firm commitment underwriting – the underwriting syndicate purchases the shares from the issuing company and then sells them to the public. The syndicate’s profit comes from the spread between the prices and it bears the risk that the actual spread earned will not be as high as anticipated (or may not even cover costs). This is the most common type of underwriting Slide 16.9 Firm Commitment Underwriting Slide 16.10 Best Efforts Underwriting Best efforts underwriting – the underwriters are legally bound to maker their “best effort” to sell the securities at the offer price, but do not actually purchase the securities from the issuing firm. In this case, the issuing firm bears the risk of the market being unwilling to buy at the offer price. C. The Aftermarket Trading period after a new issue is initially sold to the public. The syndicate, and in particular the lead underwriter, stabilizes the price by purchasing shares when the price falls below the offer price. Most IPO’s are overalloted (more shares were sold than actually existed), so the lead underwriter has a built in short position. If the price falls, then the short is covered by buying A-214 CHAPTER 16 shares in the market to support the price. If the price rises, then the short is covered by exercising the Green Shoe option. For more information, see Aggarwal, 2000, “Stabilization Activities by Underwriters After Initial Public Offerings,” The Journal of Finance, June 2000, pp. 1075 – 1103 and Ellis, Michaely and O’Hara, 2000, “When the Underwriter Is the Market Maker: An Examination of Trading in the IPO Aftermarket,” The Journal of Finance, June 2000, pp. 1039 – 1074. Ethics Note, page 533: The regulatory process attempts to ensure that investors receive enough information to make informed decisions; this is the role of the prospectus. However, this is not always the case. Brokers have been known to sell securities based on sales scripts that have little to do with the information provided in the prospectus. Also, investors often make investment decisions before receiving (or reading) the prospectus. While the behavior of the brokers is hardly ethical, it reinforces the point that you should take what the broker says with a grain of salt and always read the prospectus before making a purchase decision. D. The Green Shoe Provision The Green Shoe provision allows the underwriters to purchase additional shares (up to 15% of the issue) at the original price up to 30 days after the initial sale. This provision is used primarily when an offering goes well and the underwriters need to cover their short positions created by overallotment of the issue. See the references provided above for more information. Slide 16.11 Green Shoes and Lockups E. Lockup Agreements The lockup agreement prevents insiders from selling their shares for some period after the IPO, usually 180 days. The stock price often drops right before the lockup period expires in anticipation of a large number of shares flooding the market (excess supply causes the price to drop). 16.5. IPOs and Underpricing A. Underpricing: The 1999 - 2000 Experience Slide 16.12 IPO Underpricing CHAPTER 16 A-215 B. Evidence on Underpricing The underpricing (see a large increase above the offer price the first day of trading) of IPOs is very common. Empirical evidence suggests that it has gotten worse in recent years. As Table 15.2 points out the average underpricing has been higher from 1990 to 1999 than any other period in the study; and in 1999 the average issue was underpriced by almost 70%! Real-World Tip, page 534: An article in the Red Herring supplemental issue “Going Public 2000” discusses the issue of IPO underpricing. The title of the article is “Leaving Money on the Table, Why banks are pricing IPOs so far below what the public market seems willing to pay.” It illustrates that underpricing is not just an academic issue. As the article says, “The difference … between the offer price and the first-day close could have gone to the issuing company rather than to the chosen few investors lucky enough to be given IPO shares to flip for a big one-day take.” The author points out that a more accurate measure of “money left on the table” might be the difference between the offer price and the opening price. In 1999, five IPO’s left over $1 billion on the table using this measurement. When you consider that the underwriters generally earn a 7% spread based on the offer price, they are losing a substantial chunk of money in these transactions as well. The author argues that the wild swings are at least partially due to the unpredictability of online traders. He uses the example of Andover.net to illustrate his point. The shares of Andover.net were sold at a Dutch auction that was open to all investors large or small. Each investor tendered a secret bid. The winning bids were tallied and all winners paid the lowest accepted price. Theoretically, there should not have been a price jump because all investors who were interested could place a bid. If they were willing to pay enough, they would receive the stock. The Dutch auction led to an offer price of $18 per share, but it opened trading at $48 and closed at $63.38. The other main argument that the author gives is that the underwriter does not want to face a lawsuit for overpricing an issue. His final comment about “leaving money on the table” puts a different light on the whole process: “Everybody wins. The issuer gets its money and the publicity that comes from a huge first-trade gain, and the initial investors get a fat profit. As for the bank, it earns its fees, keeps its customers happy, and, perhaps most importantly, steers clear of the lawyers.” A-216 CHAPTER 16 Slide 16.13 Figure 16.2 Slide 16.14 Figure 16.3 Slide 16.15 Work the Web Example C. Why Does Underpricing Exist? Ethics Note, page 540: Traditionally, IPOs have been reserved for the syndicates’ best customers, but given the explosion of interest in IPOs in recent years, more opportunities are available for the average investor. One such example is the Dutch auctions that have been used to some success by W. R. Hambrecht, a relatively new investment banker. Be careful, however, if a broker tells you that you can “buy IPOs” from them. It is doubtful you can buy the IPO at the offer price; more than likely you will be buying it in the aftermarket at whatever price is then available. Real-World Tip, page 541: How good is the long-run performance of IPO firms? Not overwhelmingly good. In addition to the growing academic research, there is a good bit of institutional research suggesting that holding on to IPO stocks is a risky proposition. Consider the following table compiled by Prudential Securities: Percentage of IPO Companies reporting financial losses after: Year % of Companies 1 32% 2 37% 3 38% 4 42% 5 44% 16.6. New Equity Sales and the Value of the Firm Slide 16.16 New Equity Issues and Price Stock prices tend to decline when a company announces a seasoned equity offering. Why? A lot of the decline may be due to the asymmetric information contained by management and the signals that the choice to issue equity send to the market. -Managerial information concerning value of the stock – expectation that managers will issue equity only when they believe the current price is too high CHAPTER 16 A-217 -Debt usage – expectation that a firm will issue debt as long as it can afford to (allows stockholders to benefit more from good projects), consequently a stock issue indicates that management believes that the firm is too highly leveraged -Issue costs – equity is more expensive to issue than debt from a straight flotation cost perspective 16.7. The Costs of Issuing Securities A. The Costs of Selling Stocks to the Public The cost of issuing securities can be broken down into the following main categories: -Spread -Other direct expenses – filing fees, legal fees, etc. -Indirect expenses – opportunity costs, such as management time spent working on the issue -Abnormal returns – seasoned stock issue, the reduction in price when the announcement is made -Underpricing – IPOs -Green Shoe option – additional allotment of shares sold at offer price Other conclusions: -There are substantial economies of scale -Best efforts cost more (may be why firm commitment is the standard) -The cost of underpricing may be greater than the direct issuance costs -An IPO is more expensive than a seasoned offering Slide 16.17 Issuance Costs B. The Costs of Going Public: The Case of Multicom This section describes a real IPO and the attendant costs. The important conclusion is that, while $7.15 million was raised by selling shares, the issuing firm received only $6.6 million. Additionally, the firm had to pay $145,000 to the underwriters to defray expenses incurred. A-218 CHAPTER 16 16.8. Rights Privileged subscription – issue of common stock offered to existing stockholders. Offer terms are evidenced by warrants or rights. Rights are often traded on exchanges or over the counter. A. The Mechanics of a Rights Offering Early stages are the same as for a general cash offer, i.e., obtain approval from directors, file a registration statement, etc. The difference is in the sale of the securities. Current shareholders get rights to buy new shares. They can subscribe (buy) the entitled shares, sell the rights or do nothing. Slide 16.18 Rights Offerings: Basic Concepts B. Number of Rights Needed to Purchase as Share Number of new shares = funds to be raised / subscription price Shareholders get one right for each share already owned. The number of rights needed to buy a new share is: Number of rights needed to buy a share = # old shares / # new shares Example: Suppose a firm with 200,000 shares outstanding wants to raise $1 million through a rights offering. Each current shareholder gets one right per share held. The following table illustrates how the subscription price, number of new shares to be issued, and the number of rights needed to buy a share are related, ignoring flotation costs. Subscription Price $25 $20 $10 $5 C. # of new shares 40,000 50,000 100,000 200,000 # of rights required 5 4 2 1 The Value of a Right Slide 16.19 The Value of a Right A right has value if the subscription price is below the share price. How much a right is worth depends on how many rights it takes to buy a share and the difference between the stock price and the CHAPTER 16 A-219 subscription price. If it takes N rights to buy one share, the value of one right is equal to (initial stock price – subscription price) / (N + 1) Slide 16.20 Rights Offering Example D. Ex Rights When a privileged subscription is used, the firm sets a holder-ofrecord date. The stock sells rights-on, or cum rights, until two business days before the holder-of-record date. After that, the stock sells without the rights or ex rights. ex rights price = (1 / (N+1))(N*initial stock price + subscription price) Example: Suppose the above firm decides on a subscription price of $20, with 50,000 shares to be issued. Assume the shares outstanding currently sell for $35. Using the valuation formula and letting N = 4, a right is worth (35 – 20)/(4+1) = $3. The expected ex rights price is (1/5)(4*35 + 20) = $32 Lecture Tip, page 550: You may wish to link the stock behavior associated with the ex rights date to that of the ex dividend date. Point out that a time line could be drawn that applies to stocks trading ex rights as well as stocks trading ex dividend. Both dividend and rights declarations involve setting an ex date, which is two days before the record date. In both situations, the share price reacts on the ex date to reflect the value of the right or dividend that would not be received if the shares were purchased after the ex date. E. The Underwriting Arrangements Standby underwriting – firm makes a rights offering and the underwriter makes a commitment to “take up” (purchase) an unsubscribed shares. In return, the underwriter receives a standby fee. In addition, shareholders are usually given oversubscription privileges, the right to purchase unsubscribed shares at the subscription price. F. Rights Offers: The Case of Time Warner Slide 16.21 More on Rights Offerings A-220 CHAPTER 16 Time Warner’s rights offering was somewhat unusual. As originally proposed, the subscription price would vary, dependent upon the percentage of the issue actually sold. This feature was later dropped. As is typical of most rights offerings, only 2 percent of the rights were neither exercised nor sold. However, oversubscription rights were used to absorb the unsold stock. The underwriters’ total compensation was approximately 4 percent of the issue for management services, standby commitments, and other services. G. Effects on Shareholders Absent taxes and transaction costs, shareholder wealth is not differentially affected whether they exercise or sell their rights. Nor does it matter what subscription price the firm sets as long as it is below the market price. H. The Rights Offerings Puzzle Although there is evidence that rights offers are cheaper than general cash offers, they are relatively infrequent in the US Arguments for underwritten offerings include: 1. Underwriters get higher prices (this is dubious, given underpricing). 2. Underwriters insure against a failed offering (also dubious). 3. Offering proceeds are available sooner (questionable). 4. Advice from underwriters is valuable. 16.9. Dilution Dilution of percentage ownership Dilution of market value Dilution of book value and EPS Slide 16.22 Dilution A. Dilution of Proportionate Ownership This occurs when the firm sells stock through a general cash offer and new stock is sold to persons who previously weren’t stockholders. For many large, publicly held firms this simply isn’t an issue, the stockholders being many and varied to begin with. For some firms with a few large stockholders it may be of concern. CHAPTER 16 A-221 B. Dilution of Value: Book versus Market Values A stock’s market value will fall if the NPV of the finance project is negative and rise if the NPV is positive. Whenever a stock’s book value is greater than its market value, selling new stock will result in accounting dilution. 16.10. Issuing Long-term Debt Slide 16.23 Types of Long-Term Debt The process for issuing long-term debt is similar to issuing stock except the registration statement must include the bond indenture. Much of the corporate debt is privately placed. Term loans are direct business loans with one to five years’ maturity, usually amortized. Private placements are similar to term loans, except longer term. Commercial banks, insurance companies and other intermediaries often grant both types of loans. Differences between private placements and public issues: -No SEC registration is required for a private placement -Direct placements may have more restrictive covenants -Private placements are easier to renegotiate if necessary -Issuance costs are generally lower on private placements, although the coupon rate is generally higher It is much cheaper to issue debt than equity. Real-World Tip, page 557: Corporate issues continued to exploit the relatively low level of long-term interest rates in 1996 and 1997. In December 1996, IBM issued 100-year bonds with a face value of $850 million. As evidence of the low required return, note that the yield on these bonds is only one-tenth of one percent higher than on similar 30-year IBM bonds. In all, approximately $3.6 billion worth of 100-year bonds were issued between November 1995 and December 1996. Previous “century bond” issuers include Walt Disney Company, Coca-Cola and Yale University. Real-World Tip, page 557: An interesting article on private placements appeared in the third quarter 1997 issue of the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank’s Economic Review. An electronic version is available at http://www.dallasfed.org/htm/pubs/er.html. Stephen Prowse, an economist with the Dallas Fed, describes the structure A-222 CHAPTER 16 of the private placement market, calling private placements “a significant source of funds for U.S. corporations.” He notes that, on average, private placements tend to be “larger than bank loans and smaller than public bonds.” In a similar fashion, the maturity of privately placed debt tends to be longer than that of bank debt but shorter than that of publicly placed debt. Finally, he notes that borrowers in the private placement market tend to fall between those who rely on bank loans and those who rely on public debt, in terms of firm size. International Debt, page 557: The globalization of the financial markets is nowhere more evident than in the rise in popularity of large issues by foreign corporations and governments. In December 1993, Argentina issued $1 billion of “global bonds.” (Global bonds are offered simultaneously in all of the world’s major financial markets. First issued by the World Bank in 1989, they are often, but not always, denominated in U.S. dollars.) Investor demand was so strong that the size of the issue was raised from $750 million to $1 billion, even though these were considered junk bonds at issuance. Furthermore, a Wall Street Journal story on the Argentina issue states that it is “only the latest in a stream of global-bond offerings that have flooded the world’s markets this year.” 16.11. Shelf Registration Shelf registration – SEC Rule 415 allows a company to register all securities that it expects to issue within the next two years in one registration statement. The firm can then issue the securities in smaller increments, as funds are needed during the two-year period. Both debt and equity can be registered using Rule 415. Qualifications: -Securities must be investment grade -No debt defaults in the last three years -Market value of stock must be greater than $150 million -No violations of the Securities Act of 1934 within the last three years Slide 16.24 Shelf Registration 16.12. Summary and Conclusions Slide 16.25 Quick Quiz