Trade and Finance - WTO ECampus

advertisement

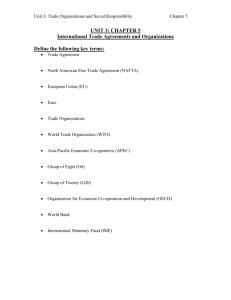

WTO E-LEARNING COPYRIGHT © Introduction to Trade Finance and the WTO OBJECTIVES Present the importance of finance for the expansion of trade, how market failures and financial crises may pose a threat to the availability of trade finance globally and hence affect global trade; Explain international initiatives that have involved the WTO in supporting the availability and affordability of trade finance, in particular in favour of developing countries. My Course series 12 I. INTRODUCTION This is a multimedia course on trade finance and the WTO. This course comprises this explanatory text, frequently asked questions and self-assessment quizzes which you can use to measure your understanding of this course. It is also supported by a video presentation covering most issues dealt with in the written presentation, entitled "Trade Finance: the Grease in the Wheels of Trade" (recently updated: "Update on Trade Finance"). Aim of this presentation The aim of this multimedia presentation is to provide elements to understand the importance of finance for the expansion of trade, how market failures and financial crises may pose a threat to the availability of trade finance globally and hence affect global trade, and to explain international initiatives that have involved the WTO in supporting the availability and affordability of trade finance, in particular in favour of developing countries. Work on trade finance has expanded in the WTO, both in the context of the WTO's Coherence Mandate, as the WTO cooperates with a wealth of international institutions in this domain, and in the framework of the WTO Working Group on Trade, Debt and Finance. The progress made towards improved availability of trade finance in least developed countries has an obvious link with Aid-for-Trade. Structure of this presentation The presentation deals with the following questions and topics: 1. Why and how does finance matters for trade? 2. Trade finance and financial crises 3. The role of the WTO in trade finance 4. The big trade collapse and role of trade finance 5. Remaining structural weaknesses in low-income countries 6. Statistical difficulties 7. Regulatory costs and trade finance 8. Looking ahead: challenges of trade finance in a context of financial deleveraging 9. Bibliography After the bibliography, one can find self-assessment questions and answers to frequently asked questions. 2 II. WHY AND HOW DOES FINANCE MATTERS FOR TRADE? Finance is the 'oil' of commerce. The expansion of international trade and investment depends on reliable, adequate, and cost-effective sources of financing. For decades, the financial sector has efficiently supported the expansion of world trade by delivering trade credit. Most trade credit is short-term (some 80% of the total, according to market surveys). Short-term trade credit is necessary for most international trade transactions because a time-lag exists between the production of the goods and their shipment by the exporter, on the one hand, and reception by the importer, on the other. Generally, exporters would require payment, at the latest, upon shipment (at the earliest upon ordering), while importers would expect to pay, at the earliest, upon reception. This time lag generally justifies the existence of a credit or a guarantee of payment. The credit can either be extended directly between firms - a supplier or a buyer's credit, or by banking intermediaries, which may offer the exporter or the importer to carry for them part of payment risk (and some other risks involved in the international trade transaction) for a fee. For example, under a letter of credit, the bank of the buyer provides a guarantee to the seller that it will be paid regardless of whether the buyer ultimately fails to pay. The risk that the buyer will fail to pay is hence transferred from the seller to the letter of credit's issuer. In many cases, international trade credit is guaranteed by some form of credit insurance. This is the case for inter-company credit, of which a large share is insured. Trade and investment credit insurers, formerly known as export credit agencies, are integral and important actors of the trade finance industry. Atradius (a company specialized in inter-company trade credit insurance), Hermes-Euler, Sinosure, and Coface are among the largest players in the trade credit insurance industry. Trade Finance is one of the safest forms of finance. While the commercial risks involved in an international trade transaction seem in principle to be larger than in a domestic trade transaction (risk of nonpayment, risk of loss or alteration of the merchandises during shipment, exchange rate risk), trade finance is generally considered to be a particularly safe form of finance, as it is underwritten by long-standing practices and procedures used by banks and traders, strong collateral and documented credit operations. According to the International Chamber of Commerce's (ICC) "trade finance loss register", the average default rate on short-term international trade credit is no larger than 0.2%, of which 60% is recovered. This low-risk, lowdefault segment of credit also generated relatively low fees per transaction, as a recognition of its relatively routine character. However, despite of trade finance being a routine task, at the same time it is systemic for trade. Despite the safety and soundness of trade finance, as described below, the availability of short-term trade credit finance can be hit by contagion from other segments of the financial industry. As indicated above, the dependence of trade on short-term financing is explained by the fact that little international trade is paid in cash, and that the very existence of a time lag (on average 90-100 days) between the export of goods and the payment, justifies the need for credit and/or a guarantee. Furthermore, non-bank intermediated, interfirm credit is often insured. Thus, in almost all cases the financial sector is involved in an international trade transaction through credit, guarantee or credit insurance. Figure 1 below shows that there is a strong correlation between the fluctuations in the volumes of trade finance and the volumes of trade flows (imports in this case), globally, over the recent period. 3 Figure 1: The relation between imports and insured trade credits in million US$ (averaged over all countries) Source: Auboin and Engemann (2012) More information More information on the mechanics of trade finance is available from key professional organizations, including the International Chamber of Commerce and the International Institute for Finance. In particular, for more information on the characteristics of trade finance, its instruments, the understanding of terms and of commercial documentation, we suggest that you either consult the specific e-training module from the International Institute for Finance; and/or the documentation made available by the website of the International Chamber of Commerce's (ICC) Banking Commission, at http://www.iccwbo.org/advocacycodes-and-rules/ 4 III. TRADE FINANCE AND FINANCIAL CRISES Until the financial crises of the 1990s and the 2008-09 financial crisis, trade finance had been taken for granted. But the crises periods created distortions in the trade finance market which made policy interventions necessary. THE ASIAN AND LATIN AMERICAN CRISES: A WARNING CALL FOR TRADE FINANCE With the expansion of global inter-bank markets, private credit markets have become dominant in the 1990's in the financing of short-term trade. Inter-bank links have been disturbed during the Asian and Latin American financial crisis of the late 1990s, when foreign "correspondent" banks reconsidered existing exposures to local banks, in the context of a solvency crisis affecting local financial institutions. In the most extreme cases, trade credit lines had been interrupted and outstanding debt left pending. Shortly after this crisis, multilateral institutions engaged with market participants and public sector actors in a "debriefing" exercise aimed at understanding why trade finance had been interrupted in this crisis, the dynamics at play, possible "market failures" and public action needed in response to such events (Box 1). Box 1: Trade finance markets in crisis: market failure? How and when? The IMF and WTO analysed the factors behind the fall in trade finance and trade flows during the financial crisis of emerging economies in Asia and Latin America in the period of 1997-2001. The IMF attributed such declines to: "[…] the interaction between perceived risks and the leveraged positions of banks, the lack of sufficient differentiation between short-term, self-liquidating trade credits, and other categories of credit exposure by rating agencies, herd behaviour among trade finance providers such as banks and trade insurers, as decision making by international providers of trade finance during crises is often dominated by perceptions rather than fundamentals, and weak domestic banking systems." The WTO pointed to the widening of the gap between the actual levels of risks and the perceived levels of risks during periods of financial crisis, as well as the confusion between the company risk and the country risk, which, altogether, led foreign banks to cut exposure for all customers. The "herd behaviour" that resulted in a general withdrawal by international banks had been encouraged by the lack of transparency and adequate information regarding companies' balance sheets in the countries concerned, as well as worrying signals sent by credit rating agencies, which, after failing to detect the onset of the crisis, downgraded the affected countries abruptly. Source: IMF (2003), Trade Finance in Financial Crises: Assessment of Key Issues, available at http://www.imf.org/external/np/pdr/cr/2003/eng/120903.htm; and, WTO (2004), Improving the Availability of Trade Finance During Financial Crises, Discussion Paper no. 2, available at http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/disc_paper2_e.htm 5 IV. THE ROLE OF THE WTO IN TRADE FINANCE The institutional case for the WTO to be concerned about the scarcity of trade finance during periods of crisis has been relatively clear since the onset of the Asian financial crisis. In situations of extreme financial crises, such as those experienced by emerging economies in the 1990's, the credit crunch had reduced access to trade finance already in the short-term segment of the market and hence trade, which would usually be the prime vector of balance of payments' recovery. The credit crunch had also affected some countries during the Asian financial crisis to the point of bringing them to a halt, as explained above. In the immediate aftermath of the currency crisis, a large amount of outstanding credit lines for trade had to be rescheduled by creditors and debtors, to re-ignite trade flows and hence the economy. Under the umbrella of the Marrakech Mandate on Coherence, the heads of the WTO, IMF and World Bank convened in 2003 an expert group of trade finance practitioners (The "Expert Group on Trade Finance") to examine what went wrong in the trade finance market and eventually to prepare contingencies. For more on the reports of the Expert Group on Trade Finance, go to: http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/devel_e/wgtdf_e.htm#trade_financing The conclusions of the experts were summarised in the above two documents, by the IMF (2003), and by the WTO (2004). The case for the involvement of international organizations and multilateral development banks has been discussed in these two documents. It is based on the idea that trade finance is, as indicated above, very secure, short-term, self-liquidating form of finance, normally not subject to many market failures. Even in some of the most acute periods of financial crises (1825, 1930), international credit lines have never been cut off. For centuries, the expansion of trade finance has depended fluid and secured financing instruments, and a wide range of credit insurance products, provided by private and public sector institutions (including national export credit agencies, regional development banks and the World Bank/IFC). The primary market for trade finance instruments was in addition backed by a rather liquid international secondary market, for example for letters of credit and bank acceptances. Trade finance normally offers a high degree of security to the trade transaction and its payment, and hence is regarded as a prime quality asset. For this reason, such prime, secure corporate lending carries normally little risk and hence a small fee (typically, a few basis points over the LIBOR for a prime borrower. However, as indicated above since the Asian crisis the trade finance market has not been totally immune from general reassessments of risk, sharp squeezes in overall market liquidity, or herd behaviour in the case of runs on currencies or repatriation of foreign assets. Director-General Lamy has convened the Expert Group on Trade Finance on a regular basis since 2007. The Expert Group on Trade Finance is playing a very useful role in identifying gaps in the trade finance markets, and to propose policy measures to fill such gaps. The Expert Group also provides a useful forum to trade finance stakeholders to discuss issues of common interest to the trade finance industry. After each meeting of the Expert Group on Trade Finance, the Secretariat reports to WTO Members through the WTO Working Group on Trade, Debt and Finance. In 2011, the Expert Group on Trade Finance was asked by the G20 to report on the effectiveness of trade finance programmes aimed at supplying trade finance to the poorest countries in the world (Annex 1). The Expert Group concluded that trade finance facilitation programmes run by regional development banks should be enhanced where they existed, and created where they did not exist yet (in Africa for example). The Expert Group has made considerable headways in several areas of trade finance, inter alia in: developing market surveys providing data and trends to identify market gaps; expanding co-operation between public and private sectors actors in periods of crisis; developing a trade credit register of millions of trade credit transactions aimed at verifying the safety of trade finance; fostering the dialogue with international prudential and other regulatory agencies; discussing ways and means to improve trade finance availability in developing countries. 6 The Expert Group on Trade Finance brings together representatives of the main players in trade finance, including the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC), regional development banks, export credit agencies and big commercial banks, as well as the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) commercial banks and other international organizations. 7 V. THE BIG TRADE COLLAPSE AND TRADE FINANCE Some of the causes of the trade credit crunch in the Asian and Latin American financial turmoil were also identified in the 2008-09 financial crisis (herd behaviour, increased gap between the level of risk and its perception, market concentration, confusion between country and counterparty risk). Since the Asian crisis period, market "thermometers" had been developed, recommended by the 2003 IMF and WTO papers, to have a better grasp on broad market trends. Both the International Chamber of Commerce’s (ICC) Banking Commission and the Bankers Association for Trade and Finance (BAFT) produced timely surveys during the crisis period (ICC (2009); IMF-BAFT (2009)). By the time of the London G-20 Summit, in April 2009, the surveys had provided a confirmation of the sharp deterioration (lower volumes, higher prices) of trade finance markets and the appearance of shortages in some regions. It appeared that the overall tightening of liquidity on inter-bank markets had affected trade credit supply by contagion: not only liquidity was insufficient to finance all requests for lending, but trade lending was also affected by the general reassessment of risk linked to the worsening of global economic activities (for a deeper examination of ICC trade finance market surveys, go to: http://www.iccwbo.org/About-ICC/Policy-Commissions/Banking/Task- forces/Market-Intelligence/ Academic interest in trade finance rose in this period, as part of the overall search for plausible explanations for the "big trade collapse", when global trade outpaced the drop in GDP by a factor that was much larger than anticipated under standard models. As summarized by Eichengreen & O’Rourke (2012): "the roots of this collapse of trade remain to be fully understood, although recent research has begun to shed light on some of the causes (see Baldwin (2009); and Chor & Manova (2012))". While most authors agree that the fall in demand has been largely responsible for the drop in trade flows, the debate focused on the extent to which other potential culprits, such as trade restrictions, a lack of trade finance, vertical specialization, and the composition of trade, may have played a role. Although the exact amount of "missing" trade finance may remain unknown globally, the literature produced in this context made progress in highlighting the wider link existing between financial conditions, trade finance and trade. Firm-level empirical work has considerably helped in establishing this causality. Box 2 provides a summary of the recent findings by academia. Box 2: Main academic work on the "trade finance channel" Amiti & Weinstein (2011) established the causality between firms' exports, their ability to obtain credit and the health of their banks. Using firm-level data from 1990 to 2010, they suggest that the trade finance channel accounted for about 20% of the decline in Japan's exports during the financial crisis of 2008-09. They showed that exporters are more reliant on trade credit and guarantees than domestic producers, and that firms working with troubled banks saw their foreign sales drop more than that of their competitors. Multinational enterprises seem less affected, notably because a large part of multinational's trade is intra-firm, which exhibits less risk, and because they are able to optimize the production-to-trade cycle, thereby minimizing working capital needs: the shorter the lag between production and payment, the less finance is a problem. In the same vein, Bricongne et al. (2012) found that sectors highly dependent on external finance have been most severely hit by the financial crisis and experienced the largest drop in their export activity in the recent crisis. Using monthly data for individual French exporters at the product and destination level, the authors also tested whether firms with heterogeneous characteristics had been affected differently by the crisis. They found, however, that small and large firms had been similarly hit by the crisis. Using data on US imports, Chor & Manova (2012) also found that credit conditions were one channel through which the crisis led to the 8 collapse in trade. Countries with tighter credit markets, measured by their interbank interest rates, exported less to the US during the recent financial crisis. This effect was especially strong for financially vulnerable industries. Financially vulnerable industries, categorized by Chor & Manova (2012) as those that require extensive external financing, have limited access to trade credit, especially during the peak of the financial crisis. Some papers, however, did not find at all or only found a limited role for trade finance in the "great trade collapse" (for example Paravisini et al. (2011), and Levchenko et al. (2010)). PUBLIC INTERVENTION There is a legitimate debate as to the extent of the gap of unfunded trade transactions during the 2008-09 crisis. However, it was difficult to deny, in the face of all available information, that the liquidity crisis in the fall of 2008 and the subsequent general re-evaluation of counterparty risk, did not affect the trade finance markets in terms of higher prices and lower volumes. In a concentrated market, there were credible concerns that a large private bank could ‘pull back’, thereby inflicting further damages to trade volumes in the short-to-medium run. One difference between leveraged finance (derivatives) and unleveraged finance (trade finance) is that the decline in unleveraged finance has a direct, immediate effect on real economy transactions (the one-to-one relationship between the value of the merchandise and its financing). The process which led the G-20 Summit in London (April 2009), in response to these concerns, to ensure support for $ 250 billion of trade finance for 2 years, has been well documented (Auboin, 2009; Chauffour & Malouche, 2011). For the original G-20 Declaration of Heads of States, and its paragraph on trade finance, see Article 22 of: http://www.canadainternational.gc.ca/g20/summit- sommet/g20/declaration_010209.aspx?view=d More information For more details on the G-20 support package, please see: http://www.voxeu.org/article/tradefinance-g20-and-follow The G-20 agreed to provide temporary and extraordinary crisis-related trade finance support that would be delivered on a basis that respected the need to avoid protectionism and would not result in the long run displacement of private market activity. This trade finance "package" involved a mix of instruments allowing for greater co-lending and risk co-sharing between banks and public-backed international and national institutions. The "follow-up" working group, established by the G-20 to monitor the implementation of the London trade finance initiative, indicated that after one year some $170 billion in extra-"capacity" have been used by markets, out of the total commitment of $ 250 billion. 9 The question of whether a specific, tailor-made trade finance "package" was required, notably at a time when central banks injected large amounts of liquidity, can be legitimately posed - as it was in the G-20. The answer was two-fold: a large share of the additional liquidity provided by central banks at the time was not intermediated into new loans. Hence, it did finance "new" trade transactions. Second, the liquidity injection of the central banks did not answer the growing problem of risk aversion, as the crisis spread. The perception of risk of non-payment increased disproportionately relative to the actual level of risk. This manifested itself in a sharp increase in the demand by traders for short-term trade credit insurance or guarantees, which the G-20 package answered by committing to supply greater "capacity" through export credit agencies. As for any public intervention, the question as to whether the G-20 package carried an element of "moral hazard" arose. The concept of moral hazard is one linked to the existence of a market failure. In addition to the recurrent factors identified in Box 1, the 2008-09 financial crisis did not fall short of market failures, starting with the failures by credit rating agencies and all other market surveillance mechanisms to detect early signs of deterioration of banks' general soundness, in particular the multiplication of off-balance sheet operations and subsequent deterioration of the risk profile of banks. Another failure of markets is, despite the experience of many periods of stress, the absence of a proper "learning curve" allowing for a better differentiation between "ill" market segments and safe ones. 10 VI. REMAINING STRUCTURAL WEAKNESSES IN LOW-INCOME COUNTRIES The G-20 package provided financing and guarantee facilities where it was needed, and it helped restore confidence. However, the road to recovery in trade finance markets has been relatively bumpy and uneven across countries. Since 2010, the recovery has been stronger in the fastest growing "routes" of trade, in line with the recovery of trade demand and improved financial market conditions. This was the case in North America, Asia, and between Asia and the rest of the World. In these areas, spreads (fees above the base interest rates) had fallen, albeit not to pre-crisis levels, with a difference between traditional trade finance instruments (letters of credit), which prices fell to low levels on the "best" Asian risks, and so-called funded trade finance products (on-balance sheet, open-account transactions), which higher prices reflected relatively large liquidity premia – the latter prices being still up to 40-50% higher than before the financial crisis. This situation was explained by a banking environment in which capital had become scarcer and the selectivity of risks greater. At the G20 Summit in Seoul, Heads of States and Governments had been sensitive to the fact that traders at the "periphery" of grand trade routes, particularly low-income countries, remained subject to difficulties in accessing trade finance at affordable cost. Under paragraph 44 of the Seoul Summit Declaration, they asked that "the G-20 Trade Finance Expert Group, together with the WTO Expert Group on Trade Finance and the OECD Expert Credit Group to further assess the current need for trade finance in LICs, and if a gap is identified, will develop and support measures to increase the availability of trade finance in LICs. We call on the WTO to review the effectiveness of existing trade finance programs for LICs and to report on actions and recommendations as for the consideration by the Sherpas through the G20 Development Working Group in February 2011." More information For more information on the G-20 statement and request in Seoul, please go to: http://www.voxeu.org/article/fixing-trade-finance-low-income-nations-g20-mandate The report from the WTO Expert Group on Trade Finance has been well received at the meeting of the G-20 Sherpas. It had revealed that only a third of the 60 poorest countries in the world benefited regularly from the services offered under these trade finance programs. The lack of risk mitigation programs in these countries partly explained the very high fees and collateral requirements paid by local importers. Such high fees were out of line with risk statistics revealed by the International Chamber of Commerce's loss default register on trade finance. Given the strong demand for these programs and their development orientation, the Director-General of the WTO supported the Report' recommendations that the priority was to strengthen trade finance facilitation programs where they existed, and create some where they did not yet exist. Time was of essence in reaching these goals. From a geographical point of view, priorities were in Africa and Asia. The WTO Expert Group on Trade Finance further confirmed the diagnosis that too many small businesses in small countries having limited financial sector capacity to oil trade were increasingly requesting support from multilateral development banks. As a result, the Director-General of the WTO committed to provide support to MDBs willing to extend their trade finance programs, as recommended by the Report. It was important that the WTO continued to address the challenges of trade finance with its multilateral partners because a lack of adequate functioning of trade finance markets could be as important a barrier to trade as more traditional obstacles. There was a risk of a market divide between the "haves" and "haves not", a risk that could be 11 increased by the "unintended consequences" of prudential regulation affecting trade finance. On that front too, a fruitful dialogue had been initiated with the competent bodies of the Financial Stability Board – with proposals expected by the G-20 Summit in Cannes. ANNEX 1: WHAT ARE THE TRADE FINANCE FACILITATION PROGRAMS OF MDBS AND THE IFC In the past decade or so, MDBs and the IFC have developed trade finance facilitation programmes aimed at supporting trade transactions at the "lower end" of trade finance markets – transactions ranging from a few thousands of dollars to a maximum of a few millions. The average of such transactions, depending on programmes and regions, is valued between $250,000 and $1 million, and hence often involves small and medium sized enterprises at both ends of the trade transaction. Trade finance facilitation programmes provide risk mitigation capacity (guarantees) to both issuing and confirming banks, to allow in particular for rapid endorsement of letters of credit – a major instrument used to finance trade transactions between developing countries players, and between developed and developing countries. The guarantee limits of these programs have been increased in the fall of 2008, as the recognition that they were playing an important role in protecting trade from vulnerable traders and banks, particularly in developing countries, during periods of crisis. The demand for these programs is still very strong in all regions of the world. Human capacity or financing limit constraints do not always allow MDBs to cover all needs. Trade Finance Facilitation programs have been developed in relatively standard way by to allow for the existence of a world-wide network allowing global commercial banks to get support/coverage from at least one development bank in supporting its customers (traders) in the various regions of the world. While the IFC started to cover African countries (in particular IDAeligible and post-conflict States), it eventually diversified its activities around the world – although its exposure in Africa as a share of its program is significant. Although most of the African IDA-eligible countries have benefited from at least one guarantee from the IFC, several Sub-Saharan countries have not been able to secure more than a few guarantees from the IFC, simply as a result of a lack of resources at the IFC. The initiation of a similar program at the African Development Bank is certainly complementing the very useful support provided by the IFC, and further help African countries that need further risk mitigation. More information For more information on trade finance activities of multilateral institutions, please consult; For the African Development Bank: http://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/initiatives- partnerships/trade-finance-initiative/ For the Asian Development Bank: http://www.adb.org/site/private-sector-financing/trade-financeprogram For the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development Bank: http://www.ebrd.com/pages/workingwithus/trade.shtml For the Inter-American Development Bank: http://www.iadb.org/en/news/news-releases/2010-1021/idb-and-trade-finance-faciliation-program,8316.html For the International Financial Corporation (World Bank Group): http://www1.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/Industry_EXT_Content/ For the Islamic Development Bank (Islamic Trade Finance Corporation): http://www.itfc- idb.org/content/what-itfc 12 Between 2008 and 2010, thanks to the exceptional mobilization of MDBs and the IFC during the crisis, the total volume of trade covered by existing trade finance facilitation programmes has increased by 150% (to a total of almost $25 billion), and the number of trade transactions covered by 75%. The support of MDBs and the IFC is therefore very important for trade in developing and low income countries. Table 1: Regional Trade Finance Facilitation Programmes (cumulative to end 2010) IFI Started Number of (year) transactions Trade credit lines/guarantees Issuing Confirming banks banks ($ billion) Total Number of Countries Covered EBRD 1999 9,800 8.8 115 644 20 IFC 2005 7,466 9.5 199 210 82 IaDB 2005 1,052 1.1 69 239 18 ADB 2004 2,433 5.2 101 101 14 13 VII. THE STATISTICAL DIFFICULTIES Why is the international community relying on surveys and not on a comprehensive set of international statistics for trade finance? Up until 2004, under the combined efforts of four international agencies, i.e. the IMF, World Bank, BIS and OECD, a series of trade finance statistics was derived from balance of payments and BIS banking statistics. Apparently the cost-to-quality ratio of these statistics led the agencies concerned to discontinue their collective effort. At the present moment the only available and reliable source of statistics concerning trade finance comes from the Berne Union database, which provides data of export credit agencies' amounts of business (mainly trade credit insurance). Survey-based data on banks is of great help in the short-run, but of limited if it was used for regular reporting given the very large amount of transactions carried by them, the wide variety and variability of trade instruments used at different periods of time (overdraft and open account; documented credit) and, more importantly, the difficulty to obtain from the main banks commercially-sensitive and proprietary data. The only way to obtain comprehensive information on an on-going basis would be through the balance of payments. Here the confidentiality issue largely disappears as data is collected on an aggregate basis (country level) and according to the resident and non-resident criterion of the balance of payments. Although short-term trade credit has been made an item for balance of payment compilers under the IMF's 5th Manual on Balance of Payment Statistics, it has always proved difficult to collect, because of the following reasons: first, it is part of overall short-term capital movements (accounting global for a third to half of total movement), and hence it makes it particularly difficult for global banks to retrieve from its various regional trade finance regional centres (say, Tokyo, Singapore, Hong-Kong, Dubai, Geneva, London) and reconcile. Equally, back-office of banks may not always be in a position to distinguish the various kinds of inter-bank lending activities, the difference between treasury management of receivables under open account operations and outright unsecured lending under such operations being extremely difficult to capture from a statistical point of view. There is also difficulties for statistical compilers in trading and financial centres to reconcile the process of intermediation between incoming or outgoing short-term capital flows, longer term flows and other flows (such as trade flows), the characteristics of such financial centres being that capital may change nature in the process of turning inflows into outflows. This has been a long-standing difficulty faced by the IMF Standing Committee on Balance of Payments statistics, which have not been made easier by the 10 or 15-fold increase in short-term capital movements in the past decade. At the bank level, ideally, pieces of sophisticated software in back-offices of any particular bank should be able to itemize trade finance deals and their counter-party for balance of payments' monthly declarations, without any discrepancy. However, the cost of such installation is very high and only a few global banks may be able to implement it, particularly given the changing nature of the market (both the ICC and IMF-BAFT survey are pointing to a relative fall in open account transactions and a re-securitization and re-intermediation of trade credits in present circumstances due to the increase risk perception), the existence of various regional centres, and the growing impact of global supply chain operations and financing in today's world trade. At the statistical level globally, it would be important in drafting and implementing the upcoming 6th manual of the Balance of payments to make the compilation of trade finance statistics a real priority. 14 VIII. REGULATORY COST AND TRADE FINANCE The expansion of world trade depends on the proper, stable, and predictable functioning of the financial system. As a result, the strengthening of the world trading system and of world prudential rules are self-supporting objectives. However, in a joint letter sent to the G-20 Leaders in Seoul, the Heads of the World Bank Group and the WTO raised the issue of the potential unintended consequences of new global prudential rules (so-called Basel II and III frameworks) on the availability of trade finance in low-income countries. While trade finance received preferential regulatory treatment under the Basel I framework, in recognition of its safe, mostly short-term character, the implementation of some provision of Basel II already proved difficult for trade. The application of risk weights and the confusion between country and counterparty risks have not been particularly advantageous for banks willing to finance trade transactions with partners from developing countries. Basel III added to these requirements a 100% leverage ratio on letters of credit, which are primarily used by developing countries. At a time when more risk-averse suppliers of trade credit revised their general exposure, the application of more stringent regulatory requirements raised doubts about profitability and incentives to engage in trade finance relative to other categories of assets. As a result, these issues have been discussed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision's Policy Development Group and the institutions concerned with trade finance, notably the WTO, the World Bank and the ICC. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision discussed which measures of the prudential regulation affecting trade finance was most detrimental to trade and trade finance availability, with a particular focus on low income countries. Based on proposals made by the WTO and the World Bank, it decided on October 25, 2011 to waive the obligation to capitalize short-term letters of credit for one full year, as average maturity was established to be between 90 and 115 days. This measure has the potential to unblock hundreds of millions of $ to finance more trade transactions. See in particular: http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs205.pdf The Director-General of the WTO continued to conduct discussions with the President of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) in 2012, with a view to clarifying the conditions of the waiver on the one-year maturity floor for self-liquidating trade finance instruments, the provisions regarding liquidity rules applying to short-term trade finance (less than 30 days), and the application of the leverage ratio to trade instruments. The Director- General hoped that the WTO would soon meet with the Basel Committee's Committee on the leverage ratio. He also confirmed with the EU Commission that the EU's planned to set the credit conversion factor for the calculation of the leverage ratio at rates below 100% for some products. In any case, the inter-institutional dialogue helped improve the understanding of trade finance products and the need to achieve adequate prudential regulation. Hence the dialogue with Basel Members should be fact-based, and ought to be fed by more data collected by the industry. There was a need, in particular, for country specific-data to be drawn from the ICC registry. The registry constituted a true public good, that had been taken seriously by the Basel Committee and that could provide important information in respect of promoting trade finance vis-à-vis rating agencies. Discussions have also taken in the WTO Expert Group on Trade Finance on other non-prudential regulatory issues described as "know-your-customers" (KYC) requirements. The discussion did not focus so much on the regulatory requirements themselves, rather on the various ways that they are being structured, defined and implemented according to different countries and regions. The Director-General provided a general perspective on this topic: the WTO was about opening trade and one way to do this was to facilitate trade- hence WTO involvement in trade finance issues; the KYC issue came in as other regulatory or compliance issues; hence the point was not whether these were needed or not, rather the focus should be whether these regulatory compliance issues, depending on how they were structured and implemented, could damage the weakest in trade markets. The WTO had a specific duty to these weak market participants - a reason why the WTO was involved in the SPS facility (STDF), for example. However, the WTO was not the sectoral regulator for such 15 topics. The main concern for the WTO was when the structure, implementation or difference between regulations had a trade clogging impact. 16 IX. LOOKING AHEAD: CHALLENGES OF TRADE FINANCE IN A CONTEXT OF FINANCIAL DELEVERAGING WILL THERE BE A LACK OF TRADE FINANCE IF THE FINANCIAL SECTOR CONTRACTS? Normally, financial turmoil is not a secular change and hence should not matter for trade in the long run if it leads to an orderly downsizing of the financial sector. One key question discussed in this section is whether a downsizing of the financial sector at large could potentially lead to a reduction in the supply of trade finance as well - and hence hamper the future expansion of trade. As suggested by the BIS 2012 Annual Report, the European and U.S. banking sectors are currently undergoing a similar period of "de-leveraging" of bank balance sheets that might result in a "welcome downsizing of the banking sector over the long run" (BIS (2012), p.69). One may argue that it will lead to more sustainable and sound financial conditions in the economy. Considering that the expansion of the global financial industry in the 2000's (be it measured by its share in GDP or the share of total credit to incomes) has been encouraged by excess "leveraging" of banks and risk-taking, a period of credit moderation and more realistic returns on capital would be yielding substantial economic benefits: more prudent lending policies, falling debt to income ratios, and a return to more normal allocation of capital resources that had been diverted from other sectors because of artificially high returns in the financial sector. However, financial crises, when triggered by the outburst of asset bubbles (real estate or financial assets), may lead to strong and lengthy corrections in the financial sector, with long-lasting effects on the economy. Downsizing can be a lengthy and bumpy process, which may also lead to adverse macroeconomic and microeconomic consequences. Figure 2 shows that after the credit-crunch in 2008-09 year-on-year growth in claims on non-financial sectors mainly remained negative in the period from 2010 till the beginning of 2012 for the Euro Area as well as the advanced economies more generally. Only emerging country bank's increased their lending activities again since 2010. Figure 2: Year-on-year growth of claims on non-banks, 2006 to 2012, in percent Sources: BIS Locational Banking Statistics, own calculations. 17 On the macro level, financial crises can have negative spill-overs in several ways: Banks may reduce the supply of new credit to economic agents in an effort to contain, or even reduce, the size of their assets in order to meet prudential ratios. Existing, over-valued assets may have to be written off or sold at a loss, with the effect of reducing bank profitability. 1 The combination of reduced profitability on bank assets and reduced new lending may be a source of contraction for the economy’s overall investment rate - both for the financial sector itself and for the economy as a whole (through reduced lending). If capital accumulation was to be impaired for a certain period of time, potential output would be reduced. According to Irving Fisher's debt-deflation mechanism financial crises usually induce a collapse in credit and a drop in the price level, hence deflation (Fisher, 1933). Both high debt ratios and deflation generally cause depressions, the problem being that the debt burden becomes even higher in real terms. As Fisher (1933), p. 344, put it: "Each dollar of debt still unpaid becomes a bigger dollar, and if the over-indebtedness with which we started was great enough, the liquidation of debts cannot keep up with the fall of prices which it causes." During the recent financial crisis, high debt and high leverage ratios have been in the centre of attention, with deflation being less of a topic. Figure 3 shows that annual growth in consumer prices decreased, but it has only been negative in 2009 for the US and China, for Europe it remained positive. In 2010 and 2011 growth in consumer prices, for the US, China and Europe, rose again. Central banks are providing the necessary liquidity to allow banks to deleverage. However, the problem of long deleveraging periods is not necessarily deflation but a misallocation of resources. New loans are displaced by old loans which may induce a long period of credit crunch leading to stagnation. Figure 3: Annual Inflation - Year-on-year change in consumer prices of all items, 2005 to 2011, in percent Sources: OECD Statistics. 1 In its 2010 Annual Report, the BIS estimated that in the two years between the onset of the financial crisis and the publication of that report, international banks had experienced cumulated losses on write-downs of assets of some $1.3 trillion, met by total recapitalization of $1.2 trillion. Since then, the BIS no longer reports this figure, but it is likely to have increased. 18 On the micro side, a long period of financial retrenchment may also yield substantial negative externalities, in particular for trade finance and hence trade. Explicitly, the allocation of capital resources may in fact not improve in a context of less credit. Long periods of credit crunches can affect certain categories of economic agents or credit, disproportionately despite their good credit or safety record. This might be the case for trade credit. Amiti & Weinstein (2011) argued that the decade-long downward adjustment of the Japanese financial industry has not been neutral for the financing of Japanese exporters. Firms working with troubled banks saw their export performance decline in absolute terms. Small and medium sized enterprises, in particular exporting ones, proved to be most affected, because they were most dependent on trade credit. The question arises as to whether the access of small and medium sized businesses to credit in general, and to trade credit in particular, will be negatively affected, in a context of increased competition within the credit committees of banks to arbitrate between the different categories of loans. One potential pitfall of a process of greater "selectivity of risk" is the possible allocation by banks of scarce capital resources to the most profitable credit segments, thereby reducing involvement in lower profitability products such as short-term trade finance. Another pitfall is that banks may focus on their most profitable customers - the larger ones. Hence, a downsizing of the financial sector and greater selectivity in risk-tasking may not act automatically in favour of an improved allocation of resources in the financial industry. Trade finance may be used as a prime vector for reducing the size of bank's balance sheet, hence achieving rapid deleveraging. Because of its short-term, roll-over nature, most trade credit lines expire after some 90 days, the average duration of transactions. By not renewing (rolling-over) or by reducing these credit lines, banking intermediaries can achieve a quick reduction of their lending (deleveraging) when needed. At the end of 2011, a few European banks have announced a reduction of trade credit lines, in an effort to restructure their balance sheets. This event proved to be short-lived. Trade finance may be negatively affected if the re-scaling of the financial sector is accompanied by a movement of "re-nationalisation" of lending activities, at the expense of cross-border lending. Already, as indicated by the BIS, many international banks have scaled back international activities: "in addition to write downs of cross-border assets during the crisis, the more expensive debt and equity funding also led to reductions in the flow of cross-border credit. As a result, credit to foreign borrowers has fallen as a share of internationally active banks' total assets […]" (see Figure 4). For European banks the share has declined by almost 30 percentage points since early 2008. The share of trade credit in this retrenchment is unknown. Not all banks have reduced foreign activities, notably Asian-based banks and other emerging countries banks. However a re-composition of the banking landscape with shifts in market share may be at play. Figure 4: Ratio of foreign to total assets, 2006 to 2012, in percent 19 Total foreign claims of BIS reporting banks headquartered in Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, and the United States as a percentage of total assets, where domestic claims are obtained from IMF IFS. Sources: IMF International Financial Statistics, BIS international banking statistics, own calculations. In the end, the direction of the international banking industry may be difficult to predict, although one might expect some reduction of its share in GDP, at least in advanced economies. A lot depends on the incentives provided by a new, reformed financial system. Normally, bank lending should be re-oriented towards more sustainable forms of finance. If balance sheet shrinkage works at the expense of "leverage finance and off-balance sheet toxic investment", hence traditional forms of finance might benefit. In that case, lending would be reoriented toward real economy financing, including trade finance, which is an important factor of trade, not only in periods of crisis but over a whole cycle (Auboin & Engemann, 2012). At the same time, if rationalization of the sector works in favour of higher yielding forms of lending, against cross border lending, the question as to whether to stay engaged in trade finance will be posed to many financial intermediaries. The question to enter or exit trade finance is not an easy one. Trade finance bears "fixed costs" of doing business, particularly costs of origination of trade finance transactions (investing in back offices, customers and sales relations, opening foreign bureau, being acquainted with international trade finance procedures). Of course, the decision to stay engaged in trade finance depends largely on the demand for real trade transactions - and hence continuation of production sharing and trade relations. 20 BIBLIOGRAPHY Amiti, M., & Weinstein, D. E. (2011). Exports and Financial Shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 1841–1877. Retrieved from http://qje.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.1093/qje/qjr033 Auboin, M. (2009). Boosting the availability of trade finance in the current crisis: Background analysis for a substantial G20 package. CEPR Policy Insight, (35). Auboin, M., & Engemann, M. (2012). Testing the Trade Credit and Trade Link: Evidence from Data on Export Credit Insurance. BIS. (2010). Triennial Central Bank Survey Report on global foreign exchange market activity in 2010 (pp. 1– 95). Baldwin, R. (2009). The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences and Prospects. VoxEU.org ebook. Bricongne, J.-C., Fontagné, L., Gaulier, G., Taglioni, D., & Vicard, V. (2012). Firms and the global crisis: French exports in the turmoil. Journal of International Economics, 87(1), 134–146. Retrieved from http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022199611000791 Chauffour, J.-P., & Malouche, M. (2011). Trade Finance During the Great Trade Collapse. Washington D.C.: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. Chor, D., & Manova, K. (2012). Off the cliff and back? Credit conditions and international trade during the global financial crisis. Journal of International Economics, 87(1), 117–133. Retrieved from http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022199611000493 Eichengreen, B., & O’Rourke, K. H. (2012). A tale of two depressions redux. VoxEU.org, 6(March). Fisher, I. (1933). The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions. Econometrica, 1(4), 337–357. ICC. (2009). Rethinking Trade Finance 2009 : An ICC Global Survey. IMF. (2003). Trade Finance in Financial Crises: Assessment of Key Issues. IMF-BAFT. (2009). Trade Finance Survey: Survey Among Banks Assessing the Current Trade Finance Environment. Knetter, M. M., & Prusa, T. J. (2003). Macroeconomic factors and antidumping filings: evidence from four countries. Journal of International Economics, 61(1), 1–17. Retrieved from http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022199602000806 Levchenko, A. A., Lewis, L. T., & Tesar, L. L. (2010). The Collapse of International Trade During the 2008-2009 Crisis: In Search of the Smoking Gun. NBER Working Paper, 16006. Paravisini, D., Rappoport, V., Schnabl, P., & Wolfenzon, D. (2011). Dissecting the Effect of Credit Supply on Trade : Evidence from Matched Credit-Export Data. NBER Working Paper, 16975. WTO. (2004). Improving the Availability of Trade Finance During Financial Crises. WTO Discussion Paper, 6. 21 ABBREVIATIONS ADB: Asian Development Bank AFDB: African Development Bank BAFT: Bankers Association for Finance and Trade BCBS: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision BIS: Bank of International Settlements BOP: Balance of Payments EBRD: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development ECA: Export Credit Agency G-20: Group of Twenty GDP: Gross Domestic Product IADB: Inter-American Development Bank ISDB: Islamic Development Bank ICC: International Chamber of Commerce IDA: International Development Association IFC: International Financial Corporation (subsidiary of the World Bank Group) IFS: International Financial Statistics IMF: International Monetary Fund MDBS: Multilateral Development Banks OECD: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development WGTDF: Working Group on Trade, Debt and Finance (body of the WTO) WTO: World Trade Organization 22 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 1. Why are public institutions involved in trade finance? Why is it not only private sector-based? Trade finance is systemic to trade flows because of the (almost) one-to-one relationship between the credit and the merchandise. Based mainly on experience gained in the past decade, there is a need to improve the stability and security of sources of trade-financing, especially to help deal with periods of financial crisis. Further efforts are needed by countries, intergovernmental organizations and all interested partners in the private sector, to explore ways and means to secure appropriate and predictable sources of trade-finance, in particular in exceptional circumstances of financial crises. Besides, there are difficult market conditions in lowincome countries, in which the financial infrastructure is not developed enough to provide adequate and affordable amounts of finance to exporters and importers. Multilateral development banks are focusing their efforts in these markets. 2. What is the relationship between WTO work on trade finance and Aid-for-Trade? Given the importance of finance for trade, the lack of availability of trade finance can act as a major barrier to trade. Under-developed financial infrastructures are undercutting the trade opportunities of developing countries. Hence, the support of multilateral development banks to trade finance, including capacity building, is Aid-for-Trade by nature. Trade finance is often mentioned as a necessary "soft infrastructure" for successful traders. As an institution geared towards the balanced expansion of world trade, the WTO is in the business of making trade possible. Its various functions include reducing trade barriers, negotiating and implementing global trade rules, and settling disputes on the basis of the rule of law. The WTO is also interested in strengthening the “supply-side” of developing countries so that they can respond to new market opportunities. To this end, it supports various initiatives aimed at improving the “trade infrastructures” of developing countries, ranging from the ability to meet international product, safety and sanitary standards, to run efficient customs, or to participate effectively to the multilateral trade negotiations by training public servants. The WTO carries out various initiatives with other partners (public and private sector institutions), in the context of its own technical assistance program, or in the context of multi-agency projects such as the Integrated Framework or the Aidfor-Trade Initiative. 3. Is there a specific legal underpinning for WTO work on trade finance? Initially, the WTO has been asked by its members at several points in recent years to examine the issue of availability of trade financing – as a key infrastructure needed by developing and least-developed countries to integrate in world trade. Paragraph 36 of the Ministerial Declaration of Doha requested WTO Members to examine, and if necessary come up with recommendations, on measures that the WTO could take, within its remit, to minimize the consequences of financial instabilities on their trade opportunities. In the context of the newly created Working Group on Trade, Debt and Finance (WGTDF), the interruptions of the flows of trade finance in emerging markets during the Asian and Latin American financial crises were quickly identified as concerns by Members, as well as the chronic difficulties of low income Members to secure more affordable flows of trade financing in the long-run. These concerns were channelled to all WTO Ministerial Meetings since Cancun (2003). At the last Ministerial Conference (MC8), Ministers reiterated their interest on WTO work in this area. Besides, the interaction with sister organizations on this issue at the border of trade and finance falls within the Coherence Mandate of 1994, which requires the Director-General to cooperate with counterparts on issues of common concern. 23 4. Is multilateral support to trade finance not generating "moral hazard" (undue support to the private sector)? Multilateral institutions are primarily concerned about boosting the availability of trade finance in the most "challenging" markets, namely in low-income economies. One particular problem in these markets is the large gap between the perception of risk in providing finance and the actual level of risk, which is not higher than in more mature markets (in other words, the rate of default on trade credit is not higher). Therefore, Trade finance facilitation Programmes run by multilateral development banks provide for risk mitigation between banks issuing and receiving trade finance. They mitigate risk by providing guarantees in case of non-payment, a very rare event. The IFC, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) participate in a global network aimed at supporting low income countries' trade and traders. 24 SELF-ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS 1. Why is trade finance considered to be the "lifeline" of trade? Only a small part of trade is paid cash. A lag exists between the optimal time at which the exporter wishes to receive payment for its export (at the latest, at the expedition of the good); and the time at which the importer would want to be paid, at the earliest, at its reception. This time lag requires a credit - which will mitigate the opposite interests of these two parties on the best timing for the payment of the merchandise. The need for credit is complemented by a need for liquidity. For example, large buyers in modern value chains (automobile producers) may rely on several suppliers for essential or less essential parts of the car to be assembled. Given the number of parts to be ordered for the assembly plants, suppliers may need to cash-in as soon as possible their receivables to be able to finance their own production. Bankers or factoring companies provide cash against receivables or equivalent bills. Trade receivables may be sold on a secondary market, in which they are appreciated as high quality, short-term securities. Trade credit in whatever form, an import loan, pre-shipment loan, bill of exchange, letter of credit and the like are oiling trade with the necessary liquidity, precisely for trade to happen. 2. How is it possible to identify market disruption in the supply of trade finance? Unfortunately, "hard" statistics are scarce in the area of trade finance. Trade credit being essentially short-term in nature, the international statistical apparatus is not able to distinguish precisely the enormous amount of short-term capital movements flowing from country to country. Nor it is able to recognize what is a threemonth trade credit from a three-month certificate of deposits. Instead, authorities rely on statistics private sector-based statistics and surveys. Such data is of great help in the short-run, providing information on broad trends on prices and volumes, but of more limited value to appreciate longer-term development. Thanks to the short-term, survey based data, authorities have been at least in a position during the recent financial crisis to substantiate claims by individual traders and bankers that gaps existed in trade finance markets. 3. What can public actors do to restore confidence in trade finance markets during financial crises? As evidenced during the 1997-1999 Asian financial crisis and the recent global financial turmoil (2009), the safest financial markets may be adversely affected by changes in perception and expectations. For example, the long-term record of paying international trade remains excellent over the recent decades - even in periods of financial stress. However, financial crises are also characterized by an upwards re-evaluation of risk perception, hence an increase in the gap between the actual level of risk and its perception. This confidence gap needs to be filed, whenever it is not reflective of more fundamental or permanent market failure. One thing that public actors can do in such circumstance is to restore market confidence, by offering more risk mitigation capacity - in order to bridge the growing gap between the risk and its heightened perception. In trade finance, risk mitigation capacity may take the form of government guarantees on expected failures to pay for traded goods - although that risk may not actually materialize. 25 4. Is there a specific problem regarding the availability of trade finance in low income countries? Yes, there is a more permanent, structural gap in the "lower-end" of the trade finance market. Traders in developing countries, in particular in low income one, face chronic in accessing affordable trade finance. The situation has worsened since the 2009 crisis. Micro, small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries have for a long time been faced with a mix of "structural" constraints, ranging from the lack of know-how in local banks, to the lack of trust requiring traders to set aside very large collaterals against a trade loan and to pay high fees for these loans. Despite this, the rate of default on trade payments in low income countries is not much higher than in other parts of the world. This situation has worsened in the post-crisis banking environment. Capital has become scarcer and the selectivity of risks greater, so negative expectations regarding the cost of doing business in poorly (or non-) rated countries are translated in either higher costs for traders locally or simply in less finance. For example, leading consulting firms active in trade finance have indicated that regular import loans charged on non-sovereign African risks are still well over 10% per annum for at least a third of African countries, and for another 20 countries or so in the rest of the world. Cash collateral requirements of up to 50% of the loan face value can be asked in addition to such high interest rates. To alleviate part of the problem, trade finance facilitation programmes have been put in place by multilateral development banks. These programmes provide risk mitigation capacity (guarantees) to both issuing and confirming banks (the banks of the importer and the exporter), to allow for rapid endorsement of letters of credit – a major instrument used to finance trade transactions between developing countries players, and between developed and developing countries. The guarantee provided by the multilateral development bank ensures that the bank (typically the bank of the exporter) accepting to confirm a letter of credit (typically issued by the bank of the importer) will be paid even if the issuer fails to pay. The multilateral development bank's payment guarantee would ensure that the exporting bank be paid. Such guarantees are rarely called in but reduce the risk aversion of conduction trade operation in low income countries - as they close part of the "structural confidence gap" between the existing level of risk and its perception. The demand for these programmes has increased during the 2009 financial crisis and has not fallen ever since. The Asian Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Inter-American Development Bank, the Islamic Development Bank, and the IFC are operating relatively similar programmes. The African Development Bank is in the process of developing its own programme. 5. What are the various groups, structures and institutional basis by which the WTO reviews work and acts on trade finance? In trade finance, the WTO operates under the overall "coherence mandate" (Article III.5 of the WTO Agreement), which provides a basis for the institution to cooperate with other international organization, notably the IMF and World Bank, on issues of common interest. The coherence mandate is defined in the 1994 Ministerial Declaration on the WTO Contribution in Achieving Greater Coherence in Economic Policy Making". At the Ministerial Conference in Doha, the WTO has been asked by its members at several points in recent years to examine the issue of availability of trade finance – as a key infrastructure needed by developing and least-developed countries to integrate in world trade. Paragraph 36 of the Ministerial Declaration of Doha requested WTO Members "to examine, and if necessary come up with recommendations, on measures that the WTO could take, within its remit, to minimize the consequences of financial instabilities on their trade opportunities". In the context of a newly created WTO body, the Working Group on Trade, Debt and Finance (WGTDF), the interruptions of the flows of trade finance in emerging markets during the 1997-99 Asian and Latin American financial crises were quickly identified as concerns by WTO Members, as well as the chronic 26 difficulties of low income Members to secure more affordable flows of trade financing in the long-run. These concerns were channelled to the WTO Ministerial Conferences in Cancun (2003), Hong-Kong (2005). For example, the report provided by the General Council of the WTO to Ministers states that: "Based mainly on experience gained in Asia and elsewhere, there is a need to improve the stability and security of sources of trade finance, especially to help deal with periods of financial crisis. Further efforts are needed by countries, intergovernmental organizations and all interested partners in the private sector, to explore ways and means to secure appropriate and predictable sources of trade finance, in particular in exceptional circumstances of financial crises." (WTO Document WT/WGTDF/2). During this period of examination, the Heads of the IMF, World Bank and the WTO agreed at the General Council Meeting on Coherence of 2002 to form an Expert Group on Trade Finance, including all interested parties, multilateral and regional public institutions, export credit agencies, private banks to examine what went wrong in this segment of financial markets, and how to create an enabling environment in local markets to provide adequate flows of trade finance on an on-going basis. Since the beginning of the crisis of the international financial system in 2007, Members have used the WGTDF to channel their concerns about the deterioration of the conditions of access to trade financing from foreign banks, not only in developing countries, but also in mature economies, which had also been hit by the scarcity and higher cost of trade finance, to a point where supply seemed to have fallen far short of demand. The Director-General of the WTO rejuvenated the Expert Group on Trade Finance, as a key group to provide information and suggest solutions. As the financial crisis spread internationally, the Expert Group on Trade Finance has been meeting regularly, and has been reporting to the WTO Members through the Working Group on Trade, Debt and Finance. In the course of 2009, it became evident that the WGTDF had become the focal point in the WTO for the examination and the follow-up of initiatives taken in support of trade finance. Elements of a trade finance support package have been discussed at the G-20 Summit in London in April 2009, to which the WTO had provided input. Since then, trade finance has become a regular feature of trade discussions in the G-20 process. 27 Videos Trade Finance: The Grease in the Wheels of Trade - http://www.swisslearn.org/wto/module36/e/ Update on Trade Finance http://etraining.wto.org/admin/files/Course_365/Videos/Update%20on%20Trade%20Finance.wmv Related videos - http://www.youtube.com/user/WTO 28