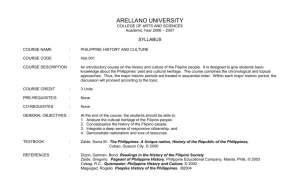

Education and Development

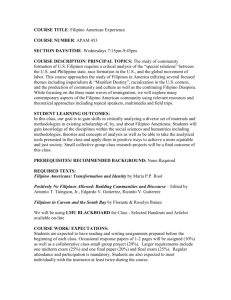

advertisement