Findings and Recommendations Health Research for Action – UC

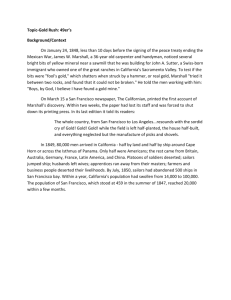

advertisement