DOC - Child and Adolescent Development Lab

advertisement

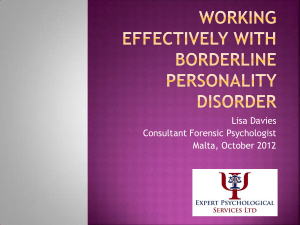

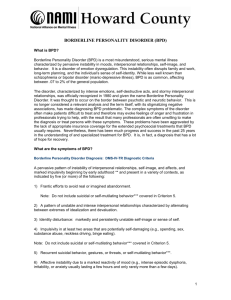

Effect of Maternal Borderline Personality Disorder on Emotional Availability in Mother-Child Interactions Jenny Macfie1, Laura Coens, Katie Fitzpatrick, Miriam Frankel, Kristen McCollum, Rebecca Trupe, & Christopher Watkins Abstract In this study we assessed emotional availability in mothers diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD) and their preschool-aged children. BPD is a severe and chronic disorder characterized by poor emotion regulation, suicidal/self-harming behavior, fear of abandonment, and difficulty with close relationships, and which may affect the mother-child relationship. Emotional availability was operationalized to include maternal sensitivity, structuring/intrusiveness, and hostility, and also child responsiveness and involvement of mother. Sixteen motherchild dyads were assessed for group differences between children with mothers who had BPD (N = 8) and normative comparisons (N = 8). As hypothesized, we found that in mother-child interactions, mothers with BPD were significantly less sensitive, more hostile, and marginally more intrusive with their children, compared with comparison mothers. Additionally, we found that children of mothers with BPD were significantly less responsive to their mothers and less involving of their mothers than were comparison children. Introduction Emotional Availability: Emotional availability is a relational construct involving emotional expression and responsiveness during dyadic interactions, and emphasizes the bidirectional quality of emotional dialogue between partners in a relationship. Within the relationship between a parent and child, it reflects emotional openness, communication, warmth, and mutual understanding. Emotional availability is characterized by emotional “attunement,” and refers not only to the parent’s emotional signals, but also to the emotional signals sent by the child, and the parent’s ability to interpret and understand the child’s emotional experience. (Biringen, 2000; Biringen & Robinson, 1991; Easterbrooks & Biringen, 2000). An emotionally available mother uses a sensitive, structuring, nonintrusive, and nonhostile style of caregiving that facilitates the child’s ability to successfully regulate emotion and behavior. This in turn enables the child to reciprocate in a responsive and involving manner towards the mother (Biringen, 2000; Biringen & Robinson, 1991; Easterbrooks & Biringen, 2000). Developmental Psychopathology Perspective: From a developmental psychopathology perspective, studying groups at high risk of developing a disorder, such as offspring of women with the disorder, may uncover pathways to disorder versus resilience and thus help inform preventive interventions (Cicchetti, 1984; Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). Recent research suggests that the offspring of women with BPD may be exposed to a combination of risk factors, which may place them at risk for emotional, behavioral, and somatic problems. Children of mothers with BPD ages 11-18, were more likely than comparisons to have nervous, inhibited, and shy temperaments, demonstrate higher scores on scales of harm avoidance, perceive their mothers as being overly protective, and show a higher prevalence of psychopathology, including severe affective instability, low self-esteem, attention/disruptive behavior problems, and suicidal thoughts (Barnow et al., 2006). The current study was designed to assess potential precursors to BPD in young children at high risk of developing the disorder in early adulthood—offspring of women with BPD. The study focused on emotional availability in the mother-child relationship. Emotional Availability and Borderline Personality Disorder: In normative samples, poor emotional availability in mother-infant dyads has been empirically associated with difficulties in emotion regulation, problems with attachment, and decreased sociability among peers (Biringen et al., 2005; Easterbrooks, Biesecker, & Lyons-Ruth, 2000; Little & Carter, 2005). Problems with emotional dysregulation in close relationships evident in individuals with BPD suggests the possibility of deficits in dyadic mother-child emotional availability when these individuals were themselves children. In turn, mothers with BPD may not be emotionally available to their own children making future 2 problems with emotion regulation in close relationships more likely(Barnow, Spitzer, Grabe, Kessler, & Freyberger, 2006; Easterbrooks et al., 2000; Little & Carter, 2005; Zanarini et al., 1997). Two studies have examined aspects of emotional availability in the infant offspring of women with BPD. In prior research, mothers with BPD have been found to be more insensitive and intrusive with their 2month-old (Crandell, Patrick, & Hobson, 2003) and 12-month-old (Hobson, Patrick, Crandell, GarciaPerez, & Lee, 2005) infants. However, no research has been conducted to assess emotional availability in mothers who have BPD and their children in the preschool period, which is when emotional self regulation is the developmental stagesalient issue. The current study was designed to fill this gap by assessing emotional availability in motherchild dyads in children age 4-6. Hypotheses: In the current study we hypothesized, that compared with normative comparisons: Mothers with BPD would be less sensitive, more intrusive, and more hostile with their children. Children of mothers with BPD would be less responsive to and involving of their mothers. Method Participants: N = 16 children, average age, n = 8 whose mothers had BPD and n = 8 whose mothers did not, were sampled Groups were matched on socioeconomic status (low), age and race. See Table 1 Mothers with BPD were referred by therapists in outpatient clinics Mothers without BPD recruited from Boys & Girls Clubs and community postering Table 1. Sample characteristics Variable Whole Sample N=16 M (SD) Child age in years 5.32 (.70) Household yearly income 34,829 (28,000) Maternal BPD n=8 M (SD) 5.42(0.60) 33,200(28,451) Comparisons N=8 M (SD) 5.19(0.84) 36,900 (30,040) t -0.66 0.26 χ2 % Mother completed high 88 school Mother single 31 Child gender (girls) 50 Child minority 0 Note. No group differences were significant. % 78 % 100 9.03 33 56 0 29 43 0 0.04 0.25 ------ Procedures and Measures BPD diagnosis: A structured interview, SCID-II (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams & Benjamin, 1997) was used to assess BPD status for both groups. Mother-child interactions: All interactions were videotaped for later coding. Storytelling (10 minutes): Experimenter handed mothers a picture book without words, and mothers were instructed to “Please read this book to your child for the next 10 minutes. It does not have any words, so read the story in a way that makes sense to you.” Puzzle-solving task (10 minutes): Experimenter placed increasingly challenging puzzles in front of the child. Mothers were told for each one, “This puzzle is for your child to complete, but feel free to give any help you think your child might need.” Emotional availability coding Curvilinear scales were recoded as per Little & Carter (2005) 3 Table 2. Overview of Emotional Availability Scales Maternal Dimensions Sensitivity, range 1-9 Refers to the mother’s awareness of and responsiveness to the child, affective quality of interactions, quality of conflict negotiations, and creativity during play 9: Optimally Sensitive 1: Highly Insensitive Positive, appropriate emotional communication; Extreme insensitivity to child’s communications interest and pleasure Active/harsh style: overbearing, harsh interaction style; Reads subtle signals and responds appropriately facial expressions of disgust and anger; abrasive tone of voice Effective resolution of conflict and distress; smooth transitions Passive/depressed style: Noninteractive and silent; disinterested Flexible and adaptive behavior; good sense of timing Structuring/Intrusiveness, range 1-5 Refers to the mother’s ability to structure or scaffold the interaction in ways that will engage the child, encourage learning, and set appropriate limits, without intruding on the child’s autonomy in an overprotective or overcontrolling manner 5: Optimal structuring / Intrusiveness 1: Non-optimal structuring, and/or Intrusiveness Follows child’s lead; bids at interaction successful No limit setting; no structure provided for child; passive, indulgent Actively involved but not overpowering; avoids interrupting Highly overstimulating; controls interaction; frequent interruptions Appropriate limit setting; uses preventive measures when possible Lack of respect for child’s wishes, abilities; may be overprotective Hostility, range 1-5 Refers to abrasive, impatient or antagonistic ways in which the mother talks to or behaves with the child, both overtly and covertly 1: Nonhostile 5: Markedly and Overtly Hostile No expressions of overt or covert hostility Overtly harsh, abrasive and demeaning General emotional climate is nonhostile Threatening or frightening behavior, threats of separation or abuse Child Dimensions Responsiveness to Mother, range 1-7 Involves the child’s ability to explore on his/her own as well as respond to the mother in an affectively positive way. This is reflected in the child’s interest, eagerness, and pleasure following a maternal bid for interaction. 7: Highly responsive 1: Unresponsive Eager, willing to engage with mother following bid Ignores bids for interaction; unresponsive or avoidant for exchange Affectively negative (whining, insulting, crying, Responds often to mother’s bids, but without urgency fearful) to mother or necessity Nonoptimal over-responsive subtype may also be May occasionally ignore mother’s bid, as when present engrossed in play Involvement of Mother, range 1-7 Refers to the child’s ability to attend to and engage the mother in interactions and invite the mother into play. 7: Highly involving 1: Nonoptimal in involving behaviors Balance between autonomous play, drawing mother Avoidant: signals not needing to play or interact with to interact mother; makes no attempt to elaborate mother initiated exchanges Varied ways of involving mother are integrated into flow of play Overinvolving: constant contact; refuses to play without mother Eager to involve mother in a comfortable, positive, non-urgent manner Note. All dimensions of emotional availability were coded with Biringen, Robinson, & Emde (1993). Structuring/Intrusiveness, Responsivity, and Involvement were then recoded as per Little & Carter (2005). The recoded ranges are noted above. For each dimension all midpoints were also utilized. 4 Results: Test of Hypotheses: Mothers with BPD were less sensitive , t(14) = 5.14, p < .0001, marginally more intrusive, t(14) = 2.08, p = .056, and more hostile with their children than were comparisons t(14) = -2.58, p = .036. Children of mothers with BPD were less responsive tot, t(14) = 3.11, p = .008, and less involving of, their mothers, t(14) = 2.43, p = .029, than were comparisons. Table 3. Emotional Availability Differences Between Maternal BPD-Child Dyads and Control Emotional BPD Control Availability Mean(SD) Range Mean(SD) Range t Mother Sensitivity 4.50(1.51) 2-7 8.00(1.20) 6-9 5.14*** Structuring/ 2.75(1.28) 1-5 4.12(1.36) 2-5 2.08† a Intrusiveness Hostility 2.31(1.44) 1-4 1.00(0.00) 1-1 2.58* Child Responsivitya 3.38(2.00) 1-6 6.00(1.31) 3-7 3.11** Involvementa 3.50(1.85) 1-6 5.50(1.41) 3-7 2.43* † Note. p < .01; *p < .05; **p <.01, ***p<.001; N = 16. All t-tests were two-tailed tests of significance. a. Values reflect recoded scores, as per Little & Carter (2005) 9.0 8.0 7.0 6.0 5.0 4.0 3.0 2.0 1.0 0.0 t en em lv vo In ty ld vi hi si C n po s es R es ld en ty i hi iv til C us os tr In lH g/ na rin er tu at M uc tr lS na ity er tiv at si M en lS na er at M BPD Comparison Discussion 5 Developmental pathways to BPD: As hypothesized, mothers with BPD were significantly less sensitive, more hostile, and marginally more intrusive in their interactions with their children when compared with comparison mothers. Also as hypothesized, children of women with BPD were significantly less involving of and less responsive to their mothers in their interactions when compared with comparison children. These findings suggest that women with BPD are less emotionally available in their interactions with their children as seen in their tendency to be more hostile and less sensitive toward their children. In turn, their children tend to be less emotionally available as seen in their tendency to be less responsive and less involving in the dyadic interactions. Conclusion: When the quality of emotional availability in the mother-infant dyad is poor, the child is likely to have affect regulation and attachment problems as well as difficulty in the area of socialization (Biringen et al., 2005). These problems are also common symptoms of BPD so may be viewed in children as precursors to the development of the disorder. Interventions to prevent the intergenerational transmission of BPD might include helping the mother with BPD learn how to increase her emotional availability to her child at the level of mother-child attachment, for example, in child-mother psychotherapy. From a developmental psychopathology perspective, the development of compromised emotional availability in mothers who have BPD and their children may inform normative development. References American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Barnow, S., Spitzer, C., Grabe, H. J., Kessler, C., & Freyberger, H. J. (2006). Individual characteristics, familial experience, and psychopathology in children of mothers with borderline personality disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 965-972. Biringen, Z. (2000). Emotional availability: Conceptualization and research findings. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 104-114. Biringen, Z., Damon, J., Grigg, W., Mone, J., Pipp-Siegel, S., Skillern, S., et al. (2005). Emotional availability: Differential predictions to infant attachment and kindergarten attachment based on observation time and context. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26, 295-308. Biringen, Z., & Robinson, J. L. (1991). Emotional availability in mother-child interactions: A reconceptualization for research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 61, 258-271. Biringen, Z., Robinson, J. L., & Emde, R. N. (1993). The Emotional Availability scales (2 nd ed.). Unpublished manual, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver. Cicchetti, D. (1984) The emergence of developmental psychopathology. Child Development, 55, 1-7. Cicchetti, D. (1993). Developmental psychopathology: Reactions, reflections, projections. Developmental Review, 13, 471-502. Crandell, L. E., Patrick, M. P., & Hobson, R. P. (2003). “Still-face” interactions between mothers with borderline personality disorder and their 2-month-old infants. British Journal of Psychiatry, 183, 239-247. Easterbrooks, M. A., Biesecker, G., & Lyons-Ruth, K. (2000). Infancy predictors of emotional availability in middle childhood: The roles of attachment security and maternal depressive symptomatology. Attachment and Human Development, 2, 170-187. Easterbrooks, M. A., & Biringen, Z. (2000). Guest editors’ introduction to the special issue: Mapping the terrain of emotional availability and attachment. Attachment and Human Development, 2, 123-129. Hobson, R. P., Patrick, M., Crandell, L., Garcia-Perez, R., & Lee, A. (2005). Personal relatedness and attachment in infants of mothers with borderline personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 17, 329-347. Little, C., & Carter, A. S. (2005). Negative emotional reactivity and regulation in 12-month-olds following emotional challenge: Contributions of maternal-infant emotional availability in a low-income sample. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26, 354-368. Sroufe, L. A., & Rutter, M. (1984). The doman of developmental psychopathology. Child Development, 55, 17-29. Zanarini, M. C., Williams, A. A., Lewis, R. E., Reich, R. B., Vera, S. C., Marino, M. F., et al. (1997). Reported pathological childhood experiences associated with the development of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 1101-1106. * This research was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Jenny Macfie [5R03MH07784101]. † This poster was presented at the Society for Research in Child Development biannual conference in April 2007. If you would like additional information, please contact Jenny Macfie at macfie@utk.edu or visit our website at http://web.utk.edu/~macfie