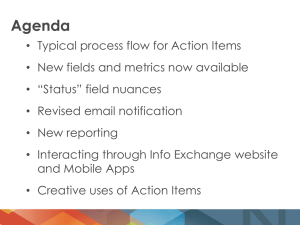

The Embedded System Theory of Groups

advertisement

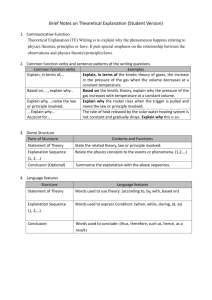

Embedded System Framework - 1 The Embedded System Theory of Groups: Toward an Integrative Theoretical Framework for the Field of Small Group Research* Professor John Gastil Department of Communication University of Washington jgastil@u.washington.edu Presented at the annual Interdisciplinary Group Research (INGRoup) Conference, Kansas City, MO, July, 2008. * This essay is being adapted for incorporation into the author’s forthcoming book, The Group in Society (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2009). Embedded System Framework - 2 Abstract This essay introduces the embedded system theoretical framework for understanding small groups. This framework aims to provide a means to better juxtapose and potentially integrate the wider range of group theories and to draw attention to the interrelationship between group processes and the their cultural and social contexts. This essay begins by clarifying the difference between theoretical frameworks and empirical theories. Movement through a range of frameworks—from early input-process-output theories to bona fide and structurational approaches leads to the development of embedded system framework. After describing this framework, it is illustrated in the context of self-managed medical teams. The conclusion suggests how the framework might stretch across the wider range of group contexts and theories. Embedded System Framework - 3 We have arrived at an exciting point in the history of small group research. There has been a resurgence of interest in—and research on—small groups, a subject that had drawn the attention of scholars at various times in the past century but also experienced periods of neglect. One challenge to studying small groups has been the interdisciplinary nature of group research. Integrative volumes published in the past decade, however, have made it considerably easier to pull together those different strands of research (e.g., Frey, 1999, 2002, 2003; Hare, 1996; Hirokawa & Poole, 1996; Levine & Moreland, 2006; Poole & Hollingshead, 2005). Some scholars have begun to call for the development of theory that spans across disciplines and group contexts. Berdahl and Henry (2005) stress that without integrative theory, any given perspective leads us to “come away with a very limited—and possibly entirely incorrect—understanding of groups” (p. 23). They recognize, however, that “the scope of the integrative problem itself” prohibits the development of such theory (p. 34). Thus, the more common approach is simply to identify broad traditions within the field, such as the seven perspectives identified by Berdahl and Henry (2005) or the nine found by Fulk and McGrath (2005). This aims simply for integration within a given domain or research approach, as some have attempted for group decision making (Hirokawa & Johnson, 1989) or group support systems (Contractor & Seibold, 1993). The most comprehensive integrative effort to date is probably structuration theory (Giddens, 1984), which Poole, Seibold, and McPhee (1985) adapted to groups. This approach, however, has proven too abstract to be of sufficient use in organizing the field of small group research. Its original purpose was to integrate sociological theories of structure and agency—to grasp “how it comes about that social activities become ‘stretched’ across wide spans of timespace” (Giddens, 1984, p. xxi). When applied to specific contexts, such as groups and Embedded System Framework - 4 organizations, the theory’s extreme level of generality led DeSanctis and Poole (1994) to reformulate it more narrowly as Adaptive Structuration Theory and in the particular context of adopting new technology. Given the importance of integrative theory yet the paucity of attempts at it, I advance in this essay one such theory, even at the risk of under-specification, over-generalization, and the other perils of such work. Toward that end, this essay begins by defining theoretical frameworks and reviewing pertinent examples, from early input-process-output theories to bona fide and structurational approaches. I then introduce the Embedded System Theoretical Framework and, by way of example, illustrate its utility in the context of self-managed medical teams. In the conclusion, I suggest how the framework could stretch across the wider range of group contexts and theories. Building a Theoretical Framework To understand how small groups behave and how they relate to larger social systems, we begin by building an abstract theoretical framework, like the skeleton of timbers, piping, and wires that frame a house. Even after the framework is fully in place, a house could end up with many different finishes and furnishings, but its frame gives you a general idea of how it will appear when it is done. Small group scholars, and social scientists generally, use “theoretical framework” loosely. Unlike “hypothesis” or “methodology,” researchers use the term only occasionally and to convey varying meanings. Contractor and Seibold (1993), for instance, use “framework” to refer to theories that yield concrete hypotheses but have connections back to more abstract meta-theory or even “grand theory,” such as Giddens’ (1984) structuration theory. A useful theoretical framework shares much in common with sound empirical theories and meets many of the same criteria (i.e., clarity, coherence, novelty, parsimony, scope, validity). Embedded System Framework - 5 Falsifiability, however, may not be as readily apparent in a theoretical framework, however, since its core empirical claims may represent well-established axioms, basic propositions that, once clearly defined, may be self-evident. Assembling such understandings into a full framework makes certain that theories built on that frame have an empirically sound foundation, and it makes it easier to see the structural similarities among a wide variety of theories. The Input-Process-Output Approach The input-process-output framework is the simplest one group researchers use (e.g., McGrath, 1964; Pavitt, 1999). This approach separates every variable into three categories: input variables, process variables, and output variables. The input-process-output framework focuses attention on three kinds of variables—those that are independent, mediating, and dependent. The inputs, such as the group’s tasks or its structure, are “independent” in that they have effects on the process and outputs but are not themselves subject to change. The output variables, such as the quality of a group decision, are “dependent” in that their values depend on the inputs and the group process. Finally, the process variables, which include the group’s discussion and its members’ ongoing thoughts and feelings, “mediate” the relationship between inputs and process; they represent the conduit between inputs and outputs. [Insert Figure1 here] The input-process-output model not only provides a good starting point for organizing group variables, it also illustrates an ongoing controversy in small group research regarding the importance of group discussion. Interaction among group members lies at the center of the inputprocess-output model, and this leads Hewes (1996) to argue that the group’s discussion really constitutes nothing more than connective tissue: Embedded System Framework - 6 We have no unambiguous evidence that group outcomes are determined either (a) by the irreducible direct causal effects of communication processes or (b) by statistical interaction effects of communication processes with variables whose values are set before the group discussion takes place (p. 179). The second of these possibilities refers to group discussion playing the role of moderator. As a moderator variable, communication does not have a direct effect on outcome but, rather, changes (i.e., “moderates”) the effect an input variable has on a group outcome. But what if the group discussion really is nothing more than a mediating variable—having no direct independent or moderating effects on group outcomes? Even then, it remains an essential part of any theory that hopes to explain group outcomes, rather than simply predicting them (Pavitt, 1999; more broadly, see Elster, 1989). In the long-term, a prediction without an adequate explanation provides an unsatisfactory account of a phenomenon. In the end, it often turns out that the incomplete explanation results in failed predictions owing to changes in variables not previously recognized as important. Taking the example of social decision schemes (Davis, 1973), the failure to incorporate measures of the group discussion itself limited the predictive power of that model. Ultimately, more complete explanation yields more precise and accurate predictions and a more thorough description of reality (within the constraints of parsimony). Groups As Systems With this emphasis on more complete explanation of group process, it becomes necessary to add onto the overly-simplistic input-process-output framework. The first addition comes from one of the broadest and oldest approaches to studying small groups, the systems perspective. This perspective assumes that the different facets of groups interrelate as parts of a system, such that changes in one variable reshape others, often in complex ways. Embedded System Framework - 7 The most comprehensive and compelling work in this tradition comes from Arrow, McGrath, and Berdahl (2000), who present a comprehensive model of group behavior in Small Groups as Complex Systems. Trained in social psychology and organizational behavior, these scholars see groups both as internally complex social-psychological processes and as organizationally-embedded entities. They begin with the premise that groups represent complex, adaptive, and dynamic systems, which means (roughly) that one can expect a group to develop increasingly complex structural properties as they adapt to changing circumstances over time. Arrow et al.’s (2000) system model stresses that group research must look at the elements of groups (e.g., individual members), the group as a coherent entity in itself (the group-system), and “the contexts in which a group is embedded” (p. 39). Most of all, researchers conceptualizing groups as systems must recognize the interplay among each of these levels of analysis. After all, the authors point out, “When the immediate embedding systems of groups are themselves complex adaptive systems [e.g., a corporation], groups can develop mutually reinforcing feedback loops with their embedding systems” (p. 207). To see these connections more clearly, Figure 2 adapts the input-process-output model to demonstrate the feedback loops back from group process and outputs to the inputs. First, note that from the systems perspective, an output of group discussion often reshapes the inputs that feed into the next discussion. Today’s dependent variable (input → output) is tomorrow’s independent variable (output → input). A non-profit board of directors, for instance, might hold a meeting that concludes with the revision of its ethics rules regarding conflicts-of-interest; those new rules become an input into its next meeting, wherein a member asks to recuse herself from a discussion in light of the new ethical guidelines. Second, the group process itself can change the inputs that continuously feed into the group’s ongoing discussion. For instance, a cult’s new members might Embedded System Framework - 8 begin a session wary of the extreme views of their discussion leader. As a result of seeing the other members repeatedly endorse the leader’s viewpoint, though, these newcomers might come to share the leader’s opinions. That attitude shift might enable the group to reach a consensus decision that would have been impossible when the discussion began. In other words, the process (group discussion) changed what were originally inputs (attitudes) and, thereby, changed the final output (decision). [Insert Figure 2 here] Organizational Context To expand this framework further, it is necessary to look more closely at the contexts in which groups exist. The “bona fide group” perspective advanced by Putnam and Stohl (1990, 1996) sheds light on the importance of thinking about groups in their organizational settings. This perspective highlights the fact that most groups emerge within or are built into rich organizational networks. As a result, the members of a given group already have membership in other groups, and these groups may have interdependent relationships, where neither can reach its goals (or their shared goals) without coordinating its actions with the other. In this sense, we would have trouble drawing rigid boundaries around any one group, as the individuals simultaneously exist within and outside that border by virtue of their other memberships. One could simply call the group’s organizational setting another “input” in the model in Figure 1, but it will prove useful to distinguish between the larger organizational context from the more proximate inputs into group discussion, such as group rules or member characteristics. In the system terms introduced earlier, the organization really constitutes a distinct level of analysis—a larger socially-constructed entity that houses within it different small groups, just as the groups themselves contain within them different individuals. Embedded System Framework - 9 The Interplay of Group and Society Before completing this theoretical framework, it is necessary to make two final additions, both of which come from Giddens’ (1984) theoretical framework, which he dubbed structuration. In building this framework, Giddens hoped to integrate conflicting sociological theories of structure, which emphasized the power of larger social forces, with theories of agency, which stressed the ability of individuals (“agents”) to make their own choices even in the midst of powerful social pressures (for a useful review, see Cohen, 1989). In Giddens’ own words, he hoped to clarify “how it comes about that social activities become ‘stretched’ across wide spans of time-space” to the point that small individual choices form the bricks and mortar of stable and farreaching social institutions and practices (Giddens, 1984, p. xxi). Figure 3 shows a sketch of the structurational framework, but the relationships among the elements in that figure require considerable elaboration. (For an account of small groups that interlaces structurational and systems theories, see Salazar, 2002, esp. pp. 188-192.) [Insert Figure 3 here] According to Giddens, the core of any social system consists of individual agents making choices of how to act in light of their own goals and their understanding of their circumstances. Giddens explains that in any given social event, though particularly in the midst of a small group gathering, “Individuals are very rarely expected ‘just’ to be co-present,” that is, merely present but not paying attention. Instead, the others there with us expect every person present to monitor one another’s actions carefully. A social occasion “demands a sort of ‘controlled alertness” (Giddens, 1984, p. 79). As participants in any small group encounter, we monitor the beliefs and aspirations of the others who are present and, more importantly, any shifts in the rules that govern the group’s behavior. To the extent that our group develops a common understanding of its rules and routine Embedded System Framework - 10 practices, it becomes integrated. The group becomes a more coherent and system-like entity. Ultimately, the systemic properties of small-scale social encounters feed back into the larger social system, which may encompass and shape the behavior of not a dozen but millions of people. (Thus, see the distinction between face-to-face “social integration” and larger “system integration” Giddens, 1984, p. 28.) Social structures and institutions, though, do not simply emerge from the voluntary behavioral choices of individuals. After all, any time we choose to say something at a social gathering, we do so in consideration of our circumstances. In the present day, for instance, if I strongly opposed gun control laws, I might express my views more freely at my afternoon Republican Party meeting than at that same evening’s public forum on school violence at the local high school. In fact, my behavior would likely differ across those two settings in more subtle ways, such as how I took turns to speak and what metaphors I might employ. In these and all other social contexts, we govern our behavior such that our words and deeds come across as meaningful, appropriate, and legitimate. The forces shaping those behavior choices are social forces. The most powerful social forces influence our behavior in ways we may not even perceive. Consider, for example, all of the laws that exist in your own society. There are millions of regulations on your behavior, from local ordinances to state and federal restrictions and requirements. On a conscious level, you may know few of these, and even fewer come to your awareness at a given time. A quick glance at the speed limit sign while driving down the freeway counts as one of the rare occasions when we deliberately check our behavior against a specific law, one that our government mentions via signposts every mile or so along the road. More pervasive than explicit laws, however, are the broad social conventions that we come to recognize more clearly only when we step outside our society. What happens when you walk Embedded System Framework - 11 hand-in-hand with a friend, shout during a disagreement, ignore an elder, or use an expletive depends critically on the time and place of your action. In one geographic location at a specific point in history, your actions could have consequences dramatically different from another—not because of written and enforced laws but because of widely shared social conventions and understandings. In spite of these differences, people persistently come to believe that their particular social system is “normal,” a sleight-of-hand that Giddens calls the “discursive ‘naturalization’ of the historically contingent circumstances and products of human action” (Giddens, 1984, pp. 25-26). Even without the propaganda consciously designed to “normalize” whatever practices our society endorses, a deeper force drives us to make our society well-ordered and “normal.” Each of us has an unconscious drive for ontological security—our sense that “the natural and social worlds are as they appear to be” (Giddens, 1984, p. 375). We protect this sense of security through “the very predictability of routine” (Giddens, 1984, p. 50). For Giddens, this need to limit our anxiety through social predictability explains how it is that we manage to create relatively social systems despite all the forces that push them to change over time. In spite of our drive for stability, a paradox of our existence is that society powerfully shapes our everyday actions, yet our everyday actions ultimately sustain (or reshape) society. In Giddens’ words, “Human history is created by intentional activities but is not an intended project; it persistently eludes efforts to bring it under conscious direction” (Giddens, 1984, p. 27). This, he calls, the “duality of structure.” Social structure is both the “medium and outcome of the conduct it recursively organizes” (Giddens, 1984, p. 374). Moreover, it is essential to recognize that social structures not only constrain us, as the foregoing examples have suggested, but they also enable us to live together. Returning to the evolutionary context at the opening of this chapter, it was only Embedded System Framework - 12 through developing shared ways of talking, stable power relationships, and a set of behavioral norms that we managed to build clans, then communities, then civilizations. In the context of our modern society, for instance, the aforementioned speed limits not only prevent you from driving faster but also enable you to travel safely by making the velocity of the other cars on the road more predictable. Poole, Seibold, and McPhee (1985, 1996) were the first to recognize the power of the structurational theoretical framework for understanding group behavior. They used structuration to better understand how groups construct shared group decisions, but their advocacy of the structurational framework never took hold. They ultimately developed a more concrete theory, the adaptive structuration model we consider later in this chapter. At a 2007 event celebrating his career accomplishments, Poole reflected that structuration theory may have proven too abstract to be of sufficient use in organizing the body of theory in small group research.1 Nonetheless, structuration makes three critical contributions to the theoretical framework I am developing. First, it stresses more clearly the societal level of analysis. It makes clear that every group exists within a larger social system that both constrains and enables group members’ behavior. Second, structuration underscores the importance of individuals’ beliefs about the larger social system. Our “reflexive monitoring” of social action helps us come to perceive the larger social system and the innumerable rules that govern behavior; our understandings of these social 1 Remarks by Marshall Scott Poole written down informally by the author at the 2007 National Communication Association panel, “A Celebration of the Career Achievement of Marshall Scott Poole.” One of the basic challenges Poole recognizes is that “it is impossible to enumerate all relevant structures a priori. The specific structures” one would potentially need to catalogue and trace “will vary from case to case, depending on the nature of the phenomenon and the context. Moreover, any enumeration [of structures[ is inherently incomplete, because any given structure involves countless other background rules and resources” (Poole, Seibold, & McPhee, 1996, p. 132). What structuration does offer, though, is a conceptual apparatus for studying this wide range of social phenomena and contexts, and it is that aspect that I incorporate into my own framework. Embedded System Framework - 13 structures become, in a sense, the most important way in which those structures exist. Sometimes, we write down understandings in records, minutes, or other documents, but most exist as a set of unwritten beliefs we hold about how society operates. Third, structuration stresses that humans have an unconscious drive toward stability and order. Given the infinite possibilities for group behavior, this offers the theorist grounds for hoping there will be sufficient regularities and patterns to build useful theories that apply fruitfully to a relatively large number of groups that operate within similar, stable social contexts. The Embedded System Theory of Small Groups At this point, I can introduce a single framework that pulls together these theoretical concepts and axioms. Figure 4 summarizes the structure of the embedded system theoretical framework. This framework derives its name from the idea of an “embedded system,” a term used commonly in computer science and engineering to refer to a sub-system built into a larger device designed to perform a specific range of tasks (Vahid, 2003). I choose to make the link to engineering and software because I think it imbues the term with a stronger metaphoric power, which is helpful to make this level of theoretical abstraction more comprehensible. When recast in social terms, this framework views groups as embedded within larger social entities, such as organizations, communities, cultures, or nations. These larger systems depend on the groups within them, because the group’s behavior can shape the character of the larger system. In turn, each group generally has a limited range of objectives, and its members even begin with a set of loose rules and instructions analogous to software. Those directives and guidelines, in turn, come from the larger systems within which the group finds itself embedded. Embedded System Framework - 14 [Insert Figure 4 here] Even in terminology, this framework draws on those reviewed above, although in somewhat different ways. Arrow et al. (2000) also refer to “embeddedness,” which is common in systems theory. Putnam and Stohl (1990) similarly stress the idea that groups are embedded in organizational contexts. Here, I stress as much their societal as organizational embeddedness. The framework I advance bears the closest resemblance to structuration theory, which I refer to as a “framework” in the body of the text to avoid confusing such a meta-theoretical work with more narrow empirical theories. By comparison with structuration, my embedded system framework has a much narrower focus on small group behavior, as opposed to the full universe of social interactions. Moreover, structuration theory does not operate with both the organizational and group levels of analysis, distinguishing instead merely between the larger system and the local social context. Finally, my framework has relatively less emphasis on structural dynamics, which structuration emphasizes at the social level (e.g., the tension between political equality and capitalist economy). These dynamics simply fall out of focus when looking most closely at the small group, though, conversely, tensions between structures at the local level of the group and organization will receive relatively more attention than they do in structuration theory. All of these amendments aim to make a theoretical framework more hospitable to integrating group theory. To be clear, the embedded system framework has stronger roots in structuration theory (Giddens, 1984) than systems theory. Both approaches emphasize the systemic qualities of social units, from small groups to large-scale societies, but the structurational approach eschews concepts and language that ascribe intentionality or requirements to social entities (Giddens, 1984, p. xxxi). See, for example, Fuchs’ (2003) structurational critique of contemporary notions of “selforganizing” systems. To be clear, though, small group theorists created models including the basic Embedded System Framework - 15 elements of the embedded system framework decades ago. For instance, McGrath and Altman (1966) distinguished the individual subsystem from the group system and the environmental suprasystem, then suggested we view these systems “not as categorically differing from each other, but as blending into each other” conceptually, as well as being related empirically (p. 38). Hare (1962) even presented a diagram of the “elements of social interaction”: on one side, biology shapes personality, which in turn shapes group behavior; on the other, environment shapes mass— then local—culture, which shapes roles and, ultimately, shapes group behavior (pp. 8-9). By way of comparison, the embedded system framework emphasizes different paths among these variables, stresses the complexity of their multiple connections, and—to kept he focus on collective behavior—deemphasizes the individual’s “intrapersonal” dramas and biological inheritances. As in structuration theory, I consider the relationships shown in Figure 4 to be simple axioms—basic assumptions already established as empirically valid and requiring no further investigation when presented at this level of abstraction. Also note that this figure, and others like it, draws causal arrows from one set of variables to another. In formal theory, it is necessary to specify more precise relationships among individual variables (see Sutton and Shaw, 2003), whereas I am to simplify the graphic representation of complex theories to foreground their general features—the direction the river flows, rather than the precise course of its tributaries. In the next main section, I will place within the embedded system framework more specific empirical theories that have required more precise formulation and direct empirical testing. In the conclusion, I show what the diagram might look like when populated with a wider array of empirical theories. Embedded System Framework - 16 Key Theoretical Concepts Before turning to the first application of the framework, I wish to provide straightforward definitions of the numerous terms that appear in Figure 4. To this point, I have focused more on the relationships among context, group process, and outcomes and less on what constitutes those elements of embedded system theory. Each of these individual concepts will receive greater attention later in this text, but reviewing them all briefly now makes it easier to see how they fit into the larger theoretical frame. Proceeding from left to right, the social system consists of regularized structures of meaning (e.g., language, symbol systems, discourses), power (e.g., economic and political institutions, patterns of domination), and norms (e.g., legal institutions, morality, etiquette). (This understanding parallels that of structuration theory; for a clear overview of these concepts, see Craib, 1992, pp. 50-58.) In conjunction with these rules, social systems also structure the distribution of resources, from information to job titles to physical materials and capital (tractors, buildings, water, etc.). A given individual can live within a single social system, but in this era of globalization and cultural diversity, a person typically feels the pull of multiple social systems operating simultaneously. All groups embed themselves within one or more social systems, but most groups embed much more precisely into a local context. Typically, a group emerges in an organizational setting: A construction company assembles a work team, a governor authorizes a commission, a union organizes a local shop, a non-profit opens a new chapter, a tribe elects its council, and jurors assemble in response to a summons. Like a social system, these commercial, political, civic, and legal organizations all have characteristics analogous to social systems. They have their own rules of meaning, power, and norms, and they allocate resources in conjunction with those rules. A Embedded System Framework - 17 group’s organizational context often determines its authority structure, but it can also shape a group’s task, structure, and other features. Not every group forms within a coherent organization. In response to a viral text-message invitation, for instance, a spontaneous group may forms as a small “flash mob” without any significant organizational properties (Rheingold, 2003). To take a less extreme example, musicians who get together to jam each weekend may do so as voluntary agents, tied to other organizations (day jobs, school, and so on), but they are not situated within any of them when they gather as an informal ensemble. The most significant instance of a group forming outside of an organizational context might be an immediate family, perhaps the most ubiquitous group form. Owing to groups like these, I say that groups exist embedded in a local context, but not necessarily an organizational one. The next part of Figure 4 encompasses features of the group and its members that earlier fell into the loose category of “inputs.” As defined in chapter 1, every group has some kind of shared purpose, which often (but not always) entails the completion of specific tasks, which range from solving engineering problems to scoring goals. Like larger social systems and the local organizational contexts, groups also have their structure—their own set of rules and allocation of resources. These structures locate authority (i.e., with a formal group leader or equally across all group members), identify and assign the different group roles, establish the medium of communication (online or face-to-face) and discussion procedures, distribute information, and more. Finally, at the individual level of analysis, the groups consist of individual agents, the individuals who make up its membership. How the group ultimately behaves will depend not only on its task and structure but also on these individuals’ conscious goals and unconscious drives, their beliefs about group, organizational, and societal structures, and their many other Embedded System Framework - 18 characteristics—personality, skills, knowledge, background, and so on. Taken together, these individual characteristics return us to the group level to note the group’s composition, the size and diversity of the group that the combination of its members yields. All of these features feed into a group’s process, which manifests itself in the interaction of the group members. These interactions consist principally of communication, verbal and nonverbal, but I use the broader term “interaction” to also encompass physical behaviors relevant to the group, such a sailor tying a sail when told to do so by a ship’s captain. While the group visibly interacts, cognitive and emotional processing takes place within the minds of each group member. Individuals each interpret what is said, take offense or feel encouraged, consider arguments, daydream, change their opinions of other members, rethink the group’s task, and so on. These often surface in new suggestions, emotional outbursts, observations, and the like, but even through the group member who sits silently through a two-hour planning flows a river of cognitive and emotional material. Finally, every group encounter yields what we once called “outcomes,” though the chain of cause-and-effect flows through them, rather than ending with them. The most self-evident outcome for groups may be decisions, which signal the completion of a specific decision-making task, as in the case of a jury’s verdict. Even when a group reaches no decision, however, it may produce formal and informal records of its meeting. These help to define what it is the group did during its time together, and this can have ramifications for the group. For instance, a task force’s meeting minutes can shape how the group members think about their future work, or (once interpreted by a manager) the group’s minutes might affect how its superiors assess its performance. Embedded System Framework - 19 Any kind of group, however, produces a more ambiguous and difficult-to-trace outcome, the individual group members’ subjective assessments of what the group accomplished. Some of the most important subjective assessments include members’ satisfaction with the group’s discussion, sense of group cohesion, judgments of the skills and motivations of other members, and commitment to the group and its larger organization. All of these impinge on future group interaction and can even potentially reshape the structure of the group’s organization or, in subtle ways, the social system itself. In this way, microscopic social experiences, such as playing soccer with a squad of multi-racial teammates, can make a small contribution toward reducing prejudice at the macro-social level (Gaertner et al., 1996). An Illusration of the Framework: Self-Managed Medical Teams The first body of research I present within the embedded system framework offers a glimpse of how its different elements can be specified more concretely to organize a testable, explanatory theory of group behavior in a specific context. The “self-managed work team” provides this first exercise in theory-building. This modern corporate group form also constitutes the first kind of archetype described herein. Also called “autonomous work groups,” “self-directed work-teams,” “employee involvement teams,” “quality circles,” and many other quasi-technical terms, these groups consist of roughly 3-15 members who are responsible for both accomplishing particular tasks and planning and monitoring their group performance (Yeatts & Seward, 2000, p. 359). In its archetypical form, managers or administrators in a larger (typically hierarchical) organization establish a self-managed work team to accomplish particular tasks that serve the organization’s broader goals. In the terms of our theoretical framework, we could say that managers draw on their understanding of the work team archetype to create and embed a new group within their organizational structure. Embedded System Framework - 20 These self-managed work teams appear with ever-increasing frequency in the largest companies in the United States and have attained tremendous popularity owing to their potential gains in productivity, innovation, and employee morale (see Moreland, Argote, & Krishnan, 1998, pp. 37-38). Just as no two snowflakes are alike, so are no two self-managed work teams identical. There are real differences, for instance, in the nature of many self-managed groups’ tasks (e.g., serving a meal versus building a laptop), and it would be foolish to make precise predictions about these teams that do not take such factors into account. Within the embedded system framework, some of these differences can be built into our theory, such as by taking into account differences in the nature of the work team’s organizational environment. To sustain sufficient theoretical scope without undue complexity, however, I will set aside some finer distinctions to develop generalizations about self-managed work team behavior. When one thinks of the range of tasks that self-managed work teams undertake, medical care may not come to mind. In the United States, in particular, the corporate model of service delivery has spread rapidly to encompass not only commercial health care providers but also public hospitals, which routinely fashion themselves on corporate principles (Wolper, 2004). In the modern practice of medicine, health maintenance organizations and other providers have come to recognize the power of bringing together doctors, nurses, and other specialists to form interdisciplinary teams that simultaneously treat every facet of an illness. Numerous societal-level influences have led to the team-emphasis, ranging from consumer advocates who press for more comprehensive and effective medical care to new legal regulations designed to promote efficient, systematic care delivery (Miccolo & Spanier, 1993). To study self-managed work teams in the health care industry, a team of communication scholars headed up by Randy Hirokawa recently surveyed a diverse array of providers and Embedded System Framework - 21 obtained 137 accounts of teams that succeeded or failed to work effectively (Hirokawa, DeGooyer, & Valde, 2003). Whether these work teams were making a medical assessment, conducting an organ transplant, or providing geriatric care, common themes emerged in their surveys. Hirokawa and his colleagues used these reports to build a “grounded” theory, a tentative theory built from a set of exploratory observations as opposed to a theory deduced from past research and validated using original data. The research team found that a range of factors appeared frequently in the success stories, with effective group structure being the most frequent theme. For instance, one survey respondent wrote that team success “was based on the fact that each one of us had a very specific job with clearly specified responsibilities and assignments.” With clear group roles delineated, “We could move in, set up, and be performing surgery within a day” (Hirokawa et al., 2003, p. 153). The survey respondents most often traced team failure back to the attributes of the team members. Specifically, Hirokawa and his colleagues found that “member incompetence was the most frequently mentioned reason for team failure.” Regardless of the particular medical team, the interviews suggested that “the expertise of the team members should at least match the most complex and challenging tasks the team is likely to encounter” (Hirokawa et al., 2003, p. 151). Both success and failure depended, in part, on the quality of the team’s interaction process. Those teams that exchanged information easily, conducted honest and thoughtful discussions, and put considerable effort into their group tasks typically reported successful outcomes. By contrast, medical providers who reported team failure often saw its roots in poorly distributed information, hasty and haphazard meetings, and a general lack of group effort. The two other common predictors of success or failure included the quality of personal relationships and group cohesion Embedded System Framework - 22 among the team members and the extent to which administrators gave the group useful feedback and necessary resources (Hirokawa et al., 2003, p. 154-155). Figure 5 summarizes these findings and show how easily the embedded system framework can organize this study’s findings into a more coherent model of effective health care teamwork. In this figure, the most critical variables and relationships appear in bold. In addition, I have enumerated the paths between each factor, and I will describe each briefly, starting with number “1”. [Insert Figure 5 here] The first path shows that a key predictor of effective group process is a combination of group structure (clarity of member roles and responsibilities) and member characteristics (medical knowledge and skills, plus motivation). The group’s timely and careful processing of information and ideas, along with effortful coordination of members’ physical tasks, feeds back into member characteristics by building up the team’s knowledge and skill base (path 2). More importantly, effective group process ultimately yields effective medical care, along with a heightened sense of group cohesion (path 3). As members’ develop a mutual respect, that feeds back along path 4 to reinforce their motivation to work with the team. The foregoing relationships represent the strongest relationships Hirokawa and his colleagues discovered, but others are apparent in their research. Path 5 suggests that effective performance can increase the likelihood of administrative support, which, in turn, provides necessary training and other forms of support (path 6). Though not the focus of their study, Hirokawa and his colleagues noted at the outset that administrators’ interest in building teams came in response to larger social forces, such as consumer advocacy groups (path 7). It is also likely that these external forces could motivate (or de-motivate) the individual team members Embedded System Framework - 23 themselves (path 8), depending on whether they felt moved in response to external pressure or resentful of outside intrusion into their organization’s internal process. Finally, one can hope that, over time, the relative success or failure of these medical teams would feed back into the larger social system, possibly resulting in legal refinements (e.g., amending malpractice statutes or Medicare coverage) to ensure that medical providers can work most effectively together. Research from widely divergent organizational settings parallels the results shown in Figure 5. One such study examined five different organizations in the Western United States, ranging from banks to public utilities. This investigation collected confidential surveys from fiftynine employees situated in ten different task groups, which included all but one of the persons initially contacted by the researchers (Bushe & Johnson, 1989). Researchers distinguished among three types of outcomes: accomplishing the task on time and to specification; achieving the highest quality in the team’s work; and producing a decision acceptable to all relevant stakeholders outside the group. The quality of the outcome flowed directly from the rigor of the group’s process, leadership (role specialization), and member skill. The task accomplishment and acceptability assessments, however, could be traced back to organizational factors, such as the project managers’ commitment to and support of the group and its work on the task. This modest study lends some additional validity to the particular model in Figure 5. Fortunately, there exists an even larger body of research consistent with the basic relationships presented therein (see, for example, Thompson, 2003). Conclusion If successful, the embedded system framework can serve to organize not only the findings of a small cluster of related studies but also larger bodies of research—perhaps even across the many subfields within the larger small group literature. As noted at the outset of this essay, group Embedded System Framework - 24 researchers currently seek such integrations, particularly across the disciplinary divides that often keep separate research conducted in communication, psychology, sociology, political science, organizational behavior, management, and related fields. As an intermediary step, scholars have instead sought to identify broad traditions within the field, thereby sweeping a loose scattering of small group theories into a more manageable set of theoretical piles (Berdahl & Henry, 2005; Fulk & McGrath, 2005; Poole et al., 2005). I count myself as one of the beneficiaries of these efforts, and in a larger manuscript (Gastil, in press), I move another step closer to theoretical integration by placing the different small group theories and perspectives into a single overarching framework. Therein, I combine (or at least juxtapose) related theories within the embedded framework in a way that shows their interrelation and potential for future synthesis. These framings of group theories have left me optimistic about the prospects for more sweeping theoretical synthesis, whereby we create theories with a broader scope and acceptable parsimony that retain considerable validity. Such theories would trace connections from group behavior to their local contexts and the larger social systems in which they embed themselves. Toward that end, Figure 6 places the most central concepts from the theories in review in Gastil (in press) into a dense (though not comprehensive) version of the embedded system theoretical framework. Make no mistake—this process of abstraction hides considerable detail, such as the interrelationships among variables within each part of the figure. Moreover, it bears repeating that this framework is just that—a framework, not a causal model. Thus, the connections among elements in Figure 6 do not specify the particular relationships between, say, group process and outcomes. The body of this book has filled in those important details, but the idea here is to Embedded System Framework - 25 step back farther than was done even in the individual chapters to see if any integrative insight might come from looking across the full diversity of group theories and contexts. [Insert Figure 6 here] Beginning at the societal level, key macro forces shaping (and shaped by) small groups include social and economic patterns of stratification that link up with the social identities deployed and reinforced (or challenged) in groups. Prevailing cultural orientations also play out (and get refined or altered) in groups through individualist vs. collectivist impulses and hierarchical vs. egalitarian norms and power relations. It is also useful to think of society’s predominant group archetypes, roles, identities, and myths all together as a linked set of resources groups draw on in defining and expressing themselves. Finally, groups exist in a legal/constitutional context that, in the United States, brings juries and committees directly into being, gives civic and social groups considerable latitude (freedom of association), but introduces some constraints (e.g., procedural fairness for registered non-profits; limits on the activities of cults, etc.). Future research could do much to help us understand how these social forces interrelate with one another, as well as the more precise ways in which they interact with group life. At the organizational level of analysis, or the local context of less formally constituted groups, three key themes arose. Institutional support and training came up repeatedly because many of the procedures, practices, and attitudes that make groups more effective require a period of learning—from informal socialization to rigorous workshop training or even counseling. The relational and power dynamics in groups also interact with the same forces in their organizational contexts. Groups reproduce, subtly challenge, or even subvert the prevailing organizational status and reward system. Finally, the organizational attitude (and formal policies) toward diversity and Embedded System Framework - 26 innovation enable or constrain groups, who may need both factors to be effective at generating new ideas, transcending limiting social identities, or rendering sound judgments. In turn, the organizational/local community culture can transform through the experiences its members have in groups—of either conforming to an ever-narrower in-group identity or creative sparking that generates new and powerful ideas and self-understandings. The structural features, membership characteristics, group processes, and immediate outcomes shown in Figure 6 are too numerous to review in detail. Nonetheless, I wish to highlight a few themes. As stressed throughout this book, these group features all interconnect, such that separating structure from process from outcome requires delicate conceptual parsing. For instance, group cohesion promotes positive social relations, which promotes a positive assessment of the group’s performance and fairness. True enough, but from another vantage point, one can see these as all parts of a whole—the strength of the group members’ network of mutual trust and affection. Moreover, the paths of the arrows in Figure 6 remind us that the variable that seems to start this causal chain (cohesion) is also an outcome. Conceptual separations between a group’s structure, process, and the cognitive residues help us see distinctions, but we must continue to see the reciprocal relationships that tie these concepts together. Those who wish to study groups could advance the field tremendously by examining some of the least investigated relationships among these diverse concepts. How, for instance, does the maturity and flexibility of a group relate to the members’ social identities? Does a strong and homogenous group identity lead more often to a regressive, inflexible group structure? Or, moving to outcomes, how closely related are assessments of one’s group process and judgments one’s attitudes toward the groups’ embodied in (or opposed by) one’s own group? Embedded System Framework - 27 At the same time, we could benefit from pulling tighter connections that one can see within this figure but that have yet to be refined through theoretical integration. For instance, the rigor of a group’s discussion process likely relates to treatment of deviance in the group, such that groups intolerant of normative deviance likely shut down open and honest discussion, as that, too, involves conflict. What, though, of groups that rigidly enforce deliberative norms? In this case, deviance itself amounts to low-quality discussion. To take another example, we could expect that information exchange processes could relate to a group’s penchant for narrative processing, such that reliance on a script or narrative could foreshorten the complete exchange of information. What of those cases, however, when a desire to explore a narrative helps to orient the group toward the unshared (or as yet unobtained) information needed to “finish” the story? Hopefully, the embedded system framework has served its purpose by providing a structure within which one can see the parallels among closely related theories. I hope that it has also helped to sketch the interconnections across even those theories addressing different (but ultimately related) aspects of small groups, as well as their important connections to larger organizational and social processes. If the framework serves its purpose, it will help to spawn more concrete theories that transform juxtapositions and speculations into robust, precise, and sufficiently complex empirical statements about how different groups operate in different social contexts.2 Strong integrative theories will pull together closely-related conceptualizations, such as the narrative theories of jury decision making and the dramatic fantasies in symbolic convergence theory, to bridge and thereby connect previously loosely-coupled (or entirely separate) literatures. The most advanced 2 At the very least, the embedded system theoretical framework could provide group scholars a new meaning for the acronym EST. Embedded System Framework - 28 integrative group theories will include estimates of relative effect sizes. Some literatures have matured to the point that we can see, for example, that a group’s cohesion has a weaker effect on decision quality than does the satisfaction of key communication functions. Strong theories will also have a scope that can encompass multiple types of groups by systematically identifying the key differences in those groups’ self-understandings, structures, situations, and purposes. Thus, instead of group type and context serving as a fencing that separates different theories, these fence posts and crossbars can be repurposed into moderating variables that give theories the complexity they need to validly account for widely varied group types and environments. The most ambitious and comprehensive theories will gather evidence on exactly how larger social structures and groups interrelate. In particular, we need to illuminate the path from the group back to larger social structures and processes. Society’s metaphorical fossil record provides some evidence of these connections, but experimental work and longitudinal field studies will prove critical as means of demonstrating unambiguous causal chains extending from the group to the society. Embedded System Framework - 29 References Arrow, H., McGrath, J. E., & Berdahl, J. L. (2000). Small groups as complex systems: Formation, coordination, development, and adaptation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Berdahl, J. L., & Henry, K. B. (2005). Contemporary issues in group research: The need for integrative theory. In S. A. Wheelan (Ed.), The Handbook of Group Research and Practice (pp. 19-37). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Bormann, E. G. (1996). Symbolic convergence theory and communication in group decision making. In R. Y. Hirokawa, & M. S. Poole, Communication And Group Decision Making, 2nd ed. (pp. 81-113). Beverly Hills: Sage. Bushe, G. R., & Johnson, A. L. (1989). Contextual and internal variables affecting task group outcomes in organizations. Group & Organization Studies, 14, 462-482. Cohen, I. (1989). Structuration theory: Anthony Giddens and the constitution of social life. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Contractor, N. S., & Seibold, D. R. (1993). Theoretical frameworks for the study of structuring processes in group decision support systems: Adaptive structuration theory and selforganizing systems theory. Human Communication Research, 19, 528-563. Craib, I. (1992). Anthony Giddens. London: Routledge. Davis, J. H. (1973). Group decision and social interaction: A theory of social decision schemes. Psychological Review, 80, 97-125. DeSanctis, G., Poole, M. S. (1994). Capturing the complexity in advanced technology use: Adaptive Structuration Theory. Organization Science, 5, 121-147. Elster, J. (1989). Nuts and bolds for the social sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Frey, L. R. (Ed.) (1999). The Handbook Of Group Communication Theory And Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Frey, L. R. (Ed.) (2002). New Directions In Group Communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Frey, L. R. (Ed.) (2003). Group Communication in Context. Manwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Fuchs, C. (2003). Structuration theory and self-organization. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 16, 133-167. Fulk, J., & McGrath, J. E. (2005). Touchstones: A framework for comparing premises of nine integrative perspectives on groups. In M. S. Poole, & A. B. Hollingshead (Eds.), Theories of Small Groups: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 397-425). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Gaertner, S. L., Rust, M. C., Dovidio, J. F., Bachman, B. A., & Anastasio, P. A. (1996). The contact hypothesis: The role of a common ingroup identity on reducing intergroup bias among majority and minority group members. In J. L. Nye & A. M. Brower (Eds.), What’s social about social cognition? (pp. 230-260). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Gastil, J. (in press). The group in society. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Giddens, A. (1984). The Constitution Of Society. Berkeley: University of California Press. Hare, A.P. (1962). Handbook of small group research. New York: Free Press. Hare, A. P. (1996). Handbook of Small Group Research, 2nd ed. New York: Free Press. Embedded System Framework - 30 Hewes, D. E. (1996). Small group communication may not influence decision making: An amplification of socio-egocentric theory. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole (Eds.), Communication and group decision making (2nd ed., pp. 179-212). Beverly Hills: Sage. Hirokawa, R. Y., DeGooyer, D. H., & Valde, K. (2003). Characteristics of effective health care teams. In R. Y. Hirokawa, R.S. Cathcart, L. A. Samovar, & L. D. Henman (Eds.), Small group communication: Theory & practice, an anthology (8th ed., pp. 148-157). Los Angeles: Roxbury. Hirokawa, R. Y., & Johnston, D. D. (1989). Toward a general theory of group decision making: Development of an integrated model. Small Group Behavior, 20, 500-523. Hirokawa, R. Y., & Poole, M. S. (1996). Communication And Group Decision Making, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Levine, J. M., & Moreland, R. L. (Eds.) (2006). Small Groups: Key Readings. New York: Psychology Press. McGrath, J. E. (1964). Social psychology: A brief introduction. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. McGrath, J. E., & Altman, I. (1966). Small group research: A synthesis and critique of the field. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Miccolo M.A. & Spanier A.H. (1993) Critical care management in. the 1990s: Making collaborative practice work. Critical Care Clinics, 9, 443-453. Moreland, R. L., Argote, L., & Krishan, R. (1998). Training people to work in groups. In R. S. Tindale et al. (Eds.), Theory and Research on Small Groups (pp. 37-60). New York: Plenum. Pavitt, C. (1999). Theorizing about the group communication-leadership relationship: Inputprocess-output and functional models. In L. R. Frey (Ed.), The handbook of group communication theory and research (pp. 313-334). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Poole, M. S., & Hollingshead, A. (Eds.) (2005). Theories Of Small Groups: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Poole, M. S., Hollingshead, A. B., McGrath, J. E., Moreland, R., & Rohrbaugh, J. (2005). Interdisciplinary perspectives on small groups. In M. S. Poole, & A. B. Hollingshead (Eds.), Theories of small groups: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 1-20). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Poole, M. S., Seibold, D. R., & McPhee, R. D. (1985). Group decision-making as a structurational process. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 71, 74-102. Poole, M. S., Seibold, D. R., & McPhee, R. D. (1996). The structuration of group decisions. In R. Y. Hirokawa, & M. S. Poole, Communication and group decision making (2nd ed., pp. 115142). Beverly Hills: Sage. Putnam, L. L., & Stohl, C. (1990). Bona fide groups: A reconceptualization of groups in context. Communication Studies, 41, 248-265. Putnam, L. L., & Stohl, C. (1996). Bona fide groups: An alternative perspective for communication and small group decision making. In R. Y. Hirokawa, & M. S. Poole (Eds.), Communication and group decision making (2nd ed., pp. 147-178). Beverly Hills: Sage. Rheingold, H. (2003). Smart mobs: The next social revolution. New York: Basic Books. Embedded System Framework - 31 Salazar, A. J. (2002). Self-organizing and complexity perspectives of group creativity: Implications for group communication. In L. R. Frey (Ed.), New directions in group communication (pp. 179-199). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Sutton, R. I., & Shaw, B. M. (2003). What theory is not. In L. L. Thompson (Ed.), The social psychology of organizational behavior: Key readings (pp. 22-32). New York: Psychology Press. Thompson, L. L. (Ed.) (2003). The social psychology of organizational behavior: Key readings. New York: Psychology Press. Vahid, F. (2003). The softening of hardware. Computer, 36(4), 27-34. Wheelan, S. A. (Ed.) (2005). The Handbook Of Group Research And Practice. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Wolper, L. F. (2004). Health Care Administration: Planning, Implementing, and Managing Organized Delivery Systems (4th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. Yeatts, D. E., & Seward, R. R. (2000). Reducing turnover and improving health care in nursing homes: The potential effects of self-managed work teams. The Gerontologist, 40, 358-363. Embedded System Framework - 32 Figure 1. The basic input-process-output theoretical framework for studying groups INPUT Tasks and/or purpose Group structure Member characteristics and beliefs PROCESS OUTPUT Group interaction Group decisions and records Cognitive/ emotional processing Subjective member assessments Embedded System Framework - 33 Figure 2. An input-process-output model of groups with feedback paths Group outcomes reshape future inputs (e.g., procedural rules) INPUT PROCESS Group process immediately resets input variables (e.g., attitudes, roles) OUTPUT Embedded System Framework - 34 Figure 3. A simplified representation of the structurational theoretical framework for studying small groups Individuals’ actions reinforce or challenge local organizational or group understandings, power relations, and norms Local context Beliefs, Motivations, and Goals Individual behavioral choices Social structures and institutions Individuals’ actions each feed back into the larger social system, serving to reproduce or gradually alter it over time. Embedded System Framework - 35 Figure 4. The embedded system theoretical framework for studying small groups Tasks and/or purpose Local context Group structure Member goals, beliefs, and characteristics Social system Group interaction Cognitive and emotional processing Group decisions and records Subjective member assessments Embedded System Framework - 36 Figure 5. A model of effective health care teamwork represented in the embedded system theoretical framework 5 4 Administrative support 6 Clarity of group roles 1 Information transfer Discussion quality Knowledge, skills, and motivation Group effort 7 8 2 Consumer pressure Legal environment 9 3 Effective delivery of health care Respect/ cohesion Embedded System Framework - 37 Figure 6. A detailed model of key group-related variables placed within the embedded system theoretical framework