Word 6.0

advertisement

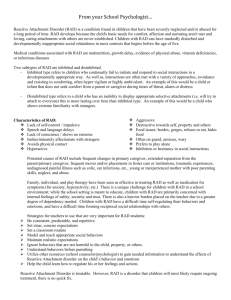

MANAGING BETTER NUMBER 16 Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform Evaluation, Audit and Review Group July 1997 © Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 1997 Published by Public Affairs Branch Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat This document is available on-line via the TBS home page on Publiservice, the federal government internal network, at the following address: http://publiservice.tbs-sct.gc.ca This series of evaluations, audit guides, reviews and studies is designed to improve Treasury Board policies and programs. Titles in this series already published: 1. Review of Operating Budgets – Delegation Framework 2. Review of Business Planning in the Government of Canada 3. Review of the Cost Recovery and User Fee Approval Process 4. Evaluation of the Policy for the Provision of Services for Employees with Disabilities 5. Audit of Service to the Public in Official Languages - Phase I – Regions of Toronto and Halifax 6. Audit on the Use of Translation Services 7. Review of the Costs Associated with the Administration of the ATIP Legislation 8. Evaluation of Telework Pilot Policy – Highlights 9. Evaluation of Telework Pilot Policy – Findings 10. Audit of Adherence to Treasury Board Information Technology Standards 11. Evaluation Framework for Early Departure Programs 12. Validation Review - Audit Guide and Departmental Monitoring Framework 13. Measuring Costs Associated With The Security Policy 14. Regulatory Reform Through Regulatory Impact Analysis: The Canadian Experience 15. 1996 Survey on the Use of the Official Languages at Work in Federal Institutions in New Brunswick Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. v MANAGEMENT’ RESPONSE .......................................................................................................vi 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 2. PROFILE .................................................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Canada's Response.......................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Organizational ................................................................................................................. 2 2.3 Regulatory Affairs Directorate ....................................................................................... 2 2.4 Impacts and Effects......................................................................................................... 2 3. EVALUATION ISSUES .............................................................................................................. 3 3.1 Measurement ................................................................................................................... 4 4. METHODS ............................................................................................................................... 7 4.1 Regulatory Culture ......................................................................................................... 7 4.2 Smarter Regulation ......................................................................................................... 8 4.3 Assessing Regulatory Burden ...................................................................................... 10 4.4 Maximizing Net Benefits ............................................................................................. 11 4.5 A World Class Regulatory Regime .............................................................................. 12 5. OPTIONS ............................................................................................................................... 13 5.1 Schedule ........................................................................................................................ 14 5.2 Options ........................................................................................................................ 15 APPENDIX A: Evaluation Issues, Concepts and Indicators APPENDIX B: An Informal Restatement of the Issues 4 Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform Executive Summary The ongoing management of the federal government's regulatory affairs is the direct responsibility of Treasury Board and its Regulatory Affairs Directorate (RAD). The long term objectives of RAD are to: i. ensure federal regulations result in the greatest possible net benefit to Canadians, and ii. ensure regulatory goals are achieved in such a cost-effective way that Canada becomes known as having the best regulatory climate for business in the industrialized world. This performance framework describes how one might assess the work of RAD in a rigorous, objective manner. Given the long term objectives of RAD it suggests that five issues should be the subject of evaluation. These are; i. Has there been a change in the regulatory culture; ii. Are regulations "smarter" than before; iii. Has the regulatory burden been reduced; iv. Have these changes maximized benefits to Canadians; and, v. Has RAD helped create a climate within which Canada is recognized as having a world class regulatory regime? The performance framework discusses how these five issues can be studied. Although there are some difficult methodological problems to resolve (e.g., developing a reasonable estimate of the costs of existing regulations) all five evaluation issues can be rigorously evaluated before the end of 1998. While completing a full assessment of RAD by 1998 is ambitious, it can be done if detailed design work begins in the near future and several studies (e.g., changes in the regulatory culture) are completed before the summer of 1997. v MANAGING BETTER Number 16 Management’ Response Background The federal government launched Regulatory Reform in 1978. Since then it has extended and enhanced Regulatory Reform through specific initiatives aimed at deregulation, through the introduction of an Annual Plan and through the introduction of a formal regulation policy. Much of the infrastructure to support Regulatory Reform has been put in place, including a range of training, networking, communication and consultation tools. The purpose of this paper is to develop a Performance Framework, which will provide a detailed plan of how regulatory reform will be assessed over the next two to four years. The framework identifies five key issues which should be the subject of evaluation. When these five questions have been answered one will be able to address the larger question of the overall effectiveness of regulatory policy and the effectiveness of Treasury Board Secretariat's support in implementing the policy. Comments The suggested evaluation approach is feasible and will provide rigorous and objective evidence about the effectiveness of the policy. The suggested schedule (completion of all five studies by the end of 1998) which will meet the needs of RAD to assess its progress is ambitious but can be completed in the time frame if detailed design of the component studies begins in the near future. Because the component studies need to be built around specific sectors (e.g., transportation, environment, health) RAD intends to work with the involved departments so that the studies can be tailored to particular circumstances and at the same time contribute to an overall evaluation of the policy. vi Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform 1. Introduction This document is a discussion paper on how one might assess the performance of Treasury Board's Regulatory Affairs Directorate (RAD). Chapter 2 presents an over view of the government's approach to regulation and the spirit that informs the efforts of RAD. It concludes with a chart which shows in a schematic manner the relationship between the activities of RAD and the long term impacts of those activities. Chapter 3 attempts to develop a list of questions (evaluation issues) one might like to ask in assessing the activities of RAD. It adopts a simplifying approach of identifying answers that might be of interest to someone outside government asking "How do you know you have been successful?" Chapter 4 describes five studies that could be carried out to answer the questions posed in Chapter 3. Chapter 5 concludes with a brief assessment of the possibility of carrying out the suggested studies and the time frame over which they might be done. It concludes by suggesting that the main decision to be made involves determining the level of effort that one might want to make in assessing the impact of RAD. 2. Profile The complexity of modern society creates conditions requiring government legislation and regulation. Concern about the environment, for example, has led to the passage of legislation and a host of supporting regulations. Indeed, environmental regulations have been a growth area since the 1970's. Regulations are not new but their scope and frequency is probably greater now than at any point in the past. Thoughtful observers have warned about the unintended consequences of legislation and the supporting regulatory framework for centuries. Three concerns have dominated the discussion. The greatest fear, much discussed in colonial America was the arbitrary nature of rules and regulations promulgated by the King and Parliament. Even when authority is limited, which is what the writers of the American constitution attempted, there is still the possibility that the complexity of legislative requirements will require the delegation of arbitrary authority to (unelected) representatives of the government of the day. This in turn can produce rules and regulations not intended by the legislature. A third concern is economic. Rules and regulations can impose great costs on individuals and organizations, making them inefficient and ineffective. A related concern is that regulations can create privileged groups and institutions that receive unwarranted benefits. All of these consequences it is argued undermine the fabric of democratic society. 1 MANAGING BETTER Number 16 While most citizens agree that rules and regulations are often necessary, there is considerable dispute about what constitutes a reasonable burden of appropriate regulation. The competitive forces of the free market, over time, put pressure on regimes that support inefficient and unnecessary regulation. Regulations cost money to design, implement, enforce and comply with. These costs show up in a number of ways (e.g., in the paper work -red tape- required to comply with a rule, or the costs of a service). Well meaning governments face two challenges. How can they determine if the existing regulatory regime is appropriate and how can they ensure that new regulations are necessary and represent a minimal burden on society? 2.1 Canada's Response Since the mid-1970's the government of Canada has instituted a number of measures to address regulatory reform. These initiatives have included the requirement that "regulatory programs" be evaluated (1977) and since the 1980's a shift in the way it views regulation and regulatory review. During the 1980's the government focused on "fairness and effectiveness" and over time changed its approach to regulatory reform. Previous initiatives (e.g., program evaluations, reduction of regulatory burden — in particular paperwork) looked at individual programs or regulations. Since 1992 the government has adopted a system of comprehensive review and management of the regulatory system. While the requirement to look at individual initiatives (e.g., as part of a program evaluation) remain in place, the government adopted a specific goal to ensure "that the use of the government's regulatory powers results in the greatest prosperity for Canadians." 2.2 Organizational Most federal regulations must be approved by the Cabinet. The ongoing management of the regulatory system is the responsibility of Treasury Board and its Regulatory Affairs Directorate (RAD). 2.3 Regulatory Affairs Directorate The long term objectives of RAD are to: i. ensure federal regulations result in the greatest possible net benefit to Canadians, and ii. ensure regulatory goals are achieved in such a cost-effective way that Canada becomes known as having the best regulatory climate for business in the industrialized world.1 1 These are objectives as established by RAD. 2 Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform It is worth noting that the first objective, reflecting government policy, requires the maximization of net benefits and not the simpler goal that benefits exceed costs. This poses some intriguing measurement problems which are discussed later in Chapter 4 of this report. The second objective is linked to the first (i.e., it is part a consequence of the first) and will only be measureable after the first objective has been at least partly achieved. RAD manages a number of efforts designed to improve the way in which regulations are made and reviewed within the government. These initiatives are designed to "regulate smarter" and to support the government's goal that "regulatory powers results in the greatest prosperity for Canadians." To further the government's goal RAD supports a series of initiatives designed to change the regulatory culture inside departments and agencies. These initiatives rely heavily on education and communication. For example, RAD established a Best Practices Committee with industry (1991) which led to the development of study modules and guides. These include publications on how to write a regulatory impact analysis (RIAS), a guide on cost-benefit analysis and a strategic approach for developing compliance strategies. In addition to developing a series of publications RAD has organized ongoing training sessions for civil servants involved in regulatory matters. These include courses, workshops, seminars and guides. Training and communication is reinforced by RAD's location within Treasury Board and the opportunity to link regulatory reform with the budget process. The 1992 budget required departments to initiate a comprehensive regulatory review which took account of the new policy. The 1995 regulatory policy requires departments to ensure that compliance and enforcement policies are articulated and resources have been approved and are adequate to discharge enforcement responsibilities and to ensure compliance where the regulation binds the government. In addition to its interest in training and communication RAD monitors regulations proposed by departments and can comment on and intercede with PCO or its own minister. Although this critique and comment function is "advisory" in nature, RAD does have influence because of its location in the system of government. While RAD has a relatively small staff complement and a limited budget it is only part of the machinery of government involved in managing regulatory matters. As mentioned above, Cabinet must approve regulations, draft regulations are reviewed by the Privy Council Office, and a parliamentary committee (The Standing Joint Committee on Regulation and other Statutory Instruments) conducts an ex post review of final regulations. The Committee can disallow regulations and has done so three times. 3 MANAGING BETTER Number 16 2.4 Impacts and Effects Over time the work of RAD should have a number of impacts and effects on Canada's regulatory regime. The main impact should be on individual departments and agencies that are responsible for the development of regulation. The impact of RAD should be evident in several areas: better education of those regulating, smarter regulations, a reduction in regulatory burden and a better understanding of regulations in the effected community (i.e., the regulated). Over time Canada's regulatory regime should result in the "greatest prosperity for Canadians." An important impact of RAD's work should be the creation of a world class regulatory regime in Canada. A schematic summary of the activities, impacts effects and long term results of the work of RAD is presented in the following chart. In looking at the chart it is important to remember that RAD is only one element (although an important one) in the larger area of regulatory reform. Regulatory reform as an initiative of government includes many organizations (e.g., Cabinet, government departments) as well as RAD. Logic Model for Regulatory Affairs Research & analysis Activities Outputs Impacts and effects RAD policy regulatory plan Increased awaremess of regulatory impacts Design and development initiatives/ programs Database of regulatory policies Increased in planning and review Coordination Guides, Publications and training to support policies and standards Increased consultations and development of a review culture Communications and information dissemination within government Changes in flexibility and development of regulation and improved regulations Policy development for regulatory affairs Communications Strong & lasting partnerships with departments/ private sector/ other government Consensus building and investment in regulatory development and review Improved & increased departmental responsibility for regulatory review Monitoring and challenge/ identifying irritants Committees Changes in regulatory practices of other governments Evaluation/review strategies/cost benefit studies Increased awareness and better understanding of regulatory review by industry More effective regulatory environment Long Term impacts and effects Improved regulatory environments for business Improved economic health, safety, and employment Improvements in quality and capability of individuals departments and firms involved in regulatory review World class regulatory regime While it is relatively easy to recognize and collect some supporting indicators of success it is more difficult to build a convincing and objective case that the desired changes have occurred and that Canadian prosperity has been enhanced. 2 Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform Strong evidence of improvement is available for certain select areas (e.g., telecommunications costs to consumers - long distance rates have declined over 30 per cent, and transportation has seen a reduction in shipping costs and improved productivity). However, it is difficult to know if these improvements have been off-set by more burdensome regulatory regimes elsewhere in the system (that is, it is difficult to answer the charge that while there may be benefits in one area there have been losses in other areas). There are also success indicators that seem to agree with common sense. For example, all other things being equal, if there is less regulation (or a change in the rate of regulation) then an independent observer would be likely to agree that there has been some improvement. For example, the number of federal regulations after 20 years of steady increase dipped below the trend line (in 1990) and there has been an absolute decline since 1993. In addition, the number of Statutory Orders and Regulations has declined from a high of almost 1169 in 1985 to the lowest ever in two decades by 1995 - 555. While these statistics are impressive they still do not provide the airtight convincing case one would like. In order to assess the progress it has made RAD needs to be able to answer a number of questions. Determining the questions to ask is the subject of the next chapter where we look at the core issues that need to be examined in an evaluation. 3. Evaluation Issues An important task in any evaluation is to shed some light on the question of what impacts and effects a program can be reasonably expected to accomplish and be held accountable for. While RAD is the focal point for the implementation of government policy on regulatory reform, RAD has few resources (some 12 full-time people) and while it has influence it does not control the development of regulations. Thus the success of RAD hinges, to some extent, on the work done in departments that develop and issue regulations. While RAD is responsible for making a contribution to the change in the government's regulatory culture it is not the only agency responsible. For those wanting to evaluate the success of RAD this raises a number of problems. Two crucial problems are discussed in the next few paragraphs. The first problem has to do with RAD's indirect influence on government department's. RAD does not develop the regulations that are put forward and cannot veto regulation that does not support the goals of the regulatory policy. RAD advises, but the final decision is made by Cabinet (i.e., is a collegial one). Thus it is difficult to isolate the contribution of RAD to overall program impacts. A second problem has to do with the attribution of results. If one is able to show that the regulatory burden has been reduced (either in a particular area or overall) how much, if any, of the reduced burden can be attributed to RAD? This problem of attribution is most difficult for program effects which are the result of a large number of different agencies. Although these are tricky issues to sort out it does make sense to conceive of the evaluation 3 MANAGING BETTER Number 16 asking two separate questions. First, did anything happen? Second, what portion of the results, if any, can be attributed to RAD and other organizations (e.g., major government departments)? Those responsible for RAD can plausibly argue that there should be impacts (flowing from the activities identified in the previous chapter) on: - the regulatory culture; - regulations (i.e., smarter regulations); and - other governments (indirectly). If and when an evaluation is completed responsible managers would like to be able to answer the question, "does RAD -encouraging implementation of the regulatory policy produce the results intended and is it possible to attribute some portion of the results to the activities of RAD?" There are four main evaluation issues that need to be addressed before this question can be answered. These are: i. Has there been a change in the regulatory culture; ii. Are regulations "smarter" than before; iii. Has the regulatory burden been reduced; and, iv. Have these changes maximized the net benefit to Canadians? A subset of this question involves determining the benefits to Canadians. A fifth evaluation issue could be: v. Has RAD helped create a climate within which Canada is recognized as having a world class regulatory regime? Since the regulatory regime and RAD impose various requirements on government departments subject to the regulatory policy, any evaluation should include the impact of RAD requirements. This can be studied as part of the issue of regulatory culture and so is not separately developed here. 3.1 Measurement Since each evaluation issue poses different difficulties in measurement each is discussed separately. 4 Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform (a) Regulatory Culture The work of RAD is designed to encourage substantial change in the way departments and agencies think about regulation. RAD has developed and published material on cost-benefit studies, compliance and the costs of regulation. It also sponsors courses designed to help those developing regulation to think through the various implications and alternatives to regulation. These activities are all designed to change the "regulatory culture" within the government. In effect these activities should lead to "smarter regulations" but one can conceive of "smarter regulations" as evidence of a change in the way people think about regulation. If RAD has an impact in this area one should be able to detect the change in the views and attitudes of two different groups. Civil servants involved in developing regulations should be able to report on the utility of the materials and courses RAD has encouraged and their views on the process of regulation. They should also be able to compare their understanding of the impacts and effects of any changes in the regulatory culture.2 People in businesses and organizations that are the subject of regulation should also be able to report on a change in the "regulatory culture." In the main they should notice greater thoughtfulness about alternatives to regulation or compliance regimes. These might be evident in such activities as early and appropriate consultations. There are a number of ways in which such changes could be measured. Indirect measures could include the amount of training provided, perceptions of RAD staff about the quality of regulation that is being proposed, increased use of cost-benefit studies and so on. (b) Smarter Regulations Since RAD supports and encourages an approach to regulation (i.e., regulate smarter) one challenge is to show that there has been a change in the type of regulation within the government (e.g., less command and control). A more convincing measure would be to show that there is a measurable difference in the quality and appropriateness of regulation over a suitable time frame (e.g., between 1992-94 and 1997-1999) within specific sectors (e.g., transportation). While the regulatory review covering 1992-1994 provides some help (e.g., it lists the number of regulations that have been revised, revoked and reviewed over the period), it does not present a readily understandable summary of the actual benefits of the changes that have been carried out. For example, Transport Canada carried out a number of significant initiatives over the period of the report (92-94) but there is little sense of the overall impact of these initiatives. Ideally, one would like to find a summary of the benefits derived from these initiatives. If appropriate measures could be developed for the 1992-94 period, these same measures 2 To facilitate the eventual study of this issue RAD should maintain a list of people who have taken the courses it sponsors. 5 MANAGING BETTER Number 16 could be used for a later period (97-98) and a more concrete estimate of progress could be made. (c) Reduction in Regulatory Burden Regulatory burden is a complex subject. Some discussions of regulatory burden focus on issues of compliance. Is it difficult to comply, how much paperwork is involved, does compliance require a change in information systems or the purchase of new equipment? Some discussions focus on the sheer volume of regulations (so many thousands of regulations and guidelines) and/or on the number of people required to operate the regulatory system (e.g., civil servants, lawyers and courts - in the case of the tax system). Appropriate measures of reduction in regulatory burden could note changes in the volume of regulation, easier compliance, fewer people required, reductions in paper work and so on. (d) Maximizing Net Benefits Since the objective of the regulatory policy is not simply to ensure that benefits are greater than costs but to show that the difference between the two has been maximized, this issue is probably the most difficult to wrestle with. One thorny problem is determining the cost of regulation. Determining the cost of regulation is difficult for a number of reasons. Some of the reasons have to do with practical difficulties (e.g., it is expensive) and others with theoretical and practical difficulties (i.e., disagreement about what to count or how to count costs). Assuming one had a complete list of all regulations determining the cost of each individual regulation would still be difficult. First, most costs have to be estimated (they are not readily identifiable in the way that one can state how much was paid for a telephone call). Estimates of costs are often done before a regulation is developed (ex ante as part of a cost benefit study) and the estimate may vary substantially from ex post measures of costs (for example, changes in the technology used may substantially reduce costs of compliance). A second problem has to do with discounting a stream of costs (borne now and into the future) into current dollars. The total cost will be highly sensitive to the discount rate chosen. Choosing an appropriate discount rate is tricky. A third problem has to do with the level of precision that can be brought to bear. Some costs are readily identified and are borne by a small group of people or organizations. Other costs are spread over large groups and may be reflected in the prices of goods and services far removed from the immediate regulation (most environmental regulations are like this). Some costs can be known precisely and others can only be represented by a sum of estimates. In theory, these different costs can be added together but the conclusions often fail to satisfy. Thus one can be told that the cost regulation is a few billion dollars or a 100 billion dollars. (e) A World Class Regulatory Regime 6 Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform An element of RAD's second objective is recognition of Canada as having a world class regulatory regime. Success in recognizing Canada's achievement requires that there be some success within Canada. Recognition that Canada has a world class regulatory regime does not require that Canada's regulatory regime is perfect or the best in the world but that it is among the best (i.e., is world class). Recognition of a world class regulatory regime is likely to happen first among "knowledgeable experts" and second within other governments (either because they recognize RAD's work or because they adopt it for their own regulatory regimes). 4. Methods 4.1 Regulatory Culture Changes in regulatory culture (assuming an impact from the government's regulatory policy and the activities of RAD) should be evident among two different groups. RAD, positioned as it is, has clients within the government (those doing the regulating) and clients outside of the government (those being regulated). Changes (in culture) should be noticed in the views/attitudes of regulators and this change should be evident to knowledgeable members of the group(s) being regulated. (a) Clients within Government RAD has a number of clients within government as a result of its advisory and oversight role. However, the clients who use the bulk of RAD "services" are those involved in preparing/reviewing regulation in regulatory departments. RAD provides a number of services to regulatory departments, for example in the development of course material and the preparation of background material and guidelines (e.g., the publication on how to think about cost-benefit studies). The purpose of this supporting material is to aid the work of regulators, in part by changing the regulatory culture. Since RAD assumes, plausibly in the view of the author of this study that these materials benefit those in the regulatory departments (i.e., are of use) then it would be reasonable to obtain the views of those who have and have not taken courses or who have used RAD prepared/sponsored material. This would allow one to do two separate things: measure changes in attitude and obtain comments on the utility of the material developed through RAD initiatives. Carrying out such a study would allow one to determine the utility of the material/services to clients directly affected and to identify any gaps in the material. This study could be carried out with a well designed survey of present and former clients of RAD (e.g., those who have taken courses). If resources are available it should be possible to interview regulators who have not been directly exposed to courses and material 7 MANAGING BETTER Number 16 sponsored by RAD. (b) Clients Outside of Government The activities of RAD over time should have a noticeable impact on those most directly affected by regulation. If there is a significant change because of RAD, regulatees should notice it and be able to comment on it. While the method for carrying out the study would involve a survey (if there is to be reasonable coverage) those to be interviewed would have to be selected for their probable knowledge of the regulatory regime in their sector (for example within a transportation company). This suggests that the analysis of the survey would properly involve looking at a series of sectors (e.g., transportation, health, agriculture) before any attempt is made to summarize findings across the larger "regulatory regime." 4.2 Smarter Regulation Assessing the extent to which improvements in the regulations (regulating smarter) have been made would require a different approach. One method would be to select a random sample of regulations that were adopted in a period before RAD was created (e.g., 1990) and compare their appropriateness with regulations put forward after the implementation of a number of RAD initiatives (1997). The two groups of regulations could be compared by an expert panel which would assess the regulations against an appropriate set of dimensions (e.g., those implicit in the Regulatory Affairs Guide Assessing Regulatory Alternatives). Creating such a review mechanism should not present insurmountable problems. However, an important issue to address is the independence of the panel. Panel members should be seen to be independent of RAD and the departments that proposed the regulations. This would require attention to sensitive design issues (e.g., the appropriateness of the sample, the dimensions the experts would review, important differences between regulatory regimes - health vs transport). However, properly carried out such a review of regulations could address virtually all aspects of this issue. Ideally one would like to draw a random sample of regulations from the two periods and compare them. There are a number of reasons for using an approach which would involve weighting the sample. First, there is considerable difference in types and impacts of regulations between sectors (e.g., health and transportation). Second, the majority of regulations (perhaps 80 per cent) have modest impacts while a small minority can have very large impacts. Accordingly, a representative sample would have to be drawn in such a way that it reflects the "size" of the regulatory burden. For example, it would be misleading to draw a sample which inevitably was weighted towards the more numerous smaller regulations. While these definition and cost issues would need to be addressed the comparison of regulations before and after RAD can proceed without resolving all of these issues. At a minimum there would need to be agreement on what "smarter regulations" look like. 8 Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform Fortunately, there are a number of assumptions about the characteristics of "good regulation" that can be found in various publications prepared by and for RAD (e.g., Assessing Regulatory Alternatives and A Strategic Approach to Developing Compliance Policies). Carrying out the type of study proposed here (a comparison of regulations before and after RAD) would involve developing a common set of dimensions against which "regulating smarter" can be assessed. This should not be a difficult process but will require some thought. Ideally, for the sample of regulations chosen for review, the supporting materials (e.g., a cost-benefit study, any considerations of alternatives and perspectives on compliance issues) should be assembled for each regulation and the package of materials reviewed by some independent group to determine whether or not there is some difference in the two periods. Such a study does not require complete agreement on the "costs" of a particular set of regulations. What would be assessed is the issue of whether or not there is an improvement in the "thinking" that went into the development of the regulations. For example, one might ask if the regulations for the later period exhibit evidence of having been more carefully examined for compliance issues, regulatory burden and possible alternatives.3 Some judgements about progress could be based on the "paper trail" associated with the regulations (e.g., the presence or absence of an appropriate cost-benefit study - or even a recognition and decision that a cost-benefit study was not appropriate). However, even in the absence of a "paper trail" or any corporate memory (since the people involved may have moved) judgements should still be possible about the "appropriateness" of the regulations proposed before and after the creation of RAD. An obvious problem is to determine who might review the material. Since the review should be independent and objective (e.g., it can be carried out for RAD but not carried out by RAD) the actual assessment would need to be carried out by some independent panel of experts. Probably the most convincing way to carry out such a review would be to have a panel of experts review the material and assess it against a previously agreed set of dimensions (e.g., how appropriate is the regulation, are there alternatives that -given our knowledge at the time- should have been considered). Judgements of this type require considerable knowledge and expertise. It would not be appropriate to ask some randomly chosen group of individuals to review the material. The method used for these types of judgements in the natural and social sciences is referred to as a peer review. The next few paragraphs discuss how this might be adapted to the current problem. 3 One source of background information could be the database RAD plans to develop on regulations RAD reviews. Consulting and Audit Canada carried out a review of some 300 regulatory impact assessments and the results of that review could be used in the proposed study. 9 MANAGING BETTER Number 16 Peer reviews of scientific papers and research are carried out for a number of reasons. For example, applications for large research grants may involve review of the proposal by a group of peers and even a visit to the site (e.g., of the laboratory or university) by the peers. This is an onerous process and has been modified for use in similar situations to reduce some of the burden (of time and cost) so that experts can carry out the review at a reasonable cost. These revised procedures are referred to as a "modified peer review" and use experts to assess one or more dimensions of a body of work. For example, a group of experts might be asked if the work being reviewed is "world class" or "excellent" or "focused on an appropriate set of issues" or "likely to be practical use to the intended client group." This modified peer review can be used to address tricky assessment issues in areas where the knowledge required for the assessment is possessed by a small group of experts (experts could be drawn from client groups). The modified process can also be used to have recognized world class experts from outside a particular country (in this case Canada) comment on prepared material. This has the added benefit of allowing the assessment to be "more independent" than might be possible inside a country where the group of experts is necessarily small, most are known to each other and many might have worked on the material to be reviewed. 4.3 Assessing Regulatory Burden One of the most significant direct impacts that result from the work of RAD should be a reduction in the regulatory burden faced by Canadians as a result of federal government requirements. One way to assess whether or not the regulatory burden is likely to be reduced is addressed in the study described above on changes to the regulation (regulating smarter). If the regulatory culture improves and as a consequence one "regulates smarter" then the regulatory burden, all other things being equal should be reduced. A more direct impact should be actual reductions in the regulatory burden. These, it must be acknowledged are difficult to measure. In order to deal with this problem a study could be carried out that attempts to measure reductions in regulatory burden over time. Again the sensible approach would be to compare a group of regulatory initiatives (perhaps from the 1992-1994) review and do a follow-up which would look at what actually happened. This information supplemented by other measures (e.g., the fact that the number of regulations has dropped substantially) and the other studies proposed as part of this review should allow one to say with some confidence that a substantial body of credible evidence is available to show that the regulatory burden has decreased. Unlike the previous study which would depend on a modified peer review exercise for its credibility, the reduction in burden (over time) could be carried out by a study team that used existing, available techniques and measures to estimate the reduction in the regulatory burden. Since there is a large number of initiatives mentioned in the 1992-1994 review it might be appropriate to identify the major issues and develop a credible estimate of the degree to which the burden has been reduced and the benefits (if possible, monetary or 10 Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform savings in time) calculated for the "significant initiatives." If one can show that these benefits are significant and likely to be far greater than any recent (i.e., additional) burdens then a reasonable conclusion would be that the regulatory burden has been reduced. There are a number of challenges in carrying out this study. First, a balanced set of the major initiatives from the 1992-1994 review would have to be identified. Second, each of the chosen initiatives would have to be examined to determine the type of savings (benefits) likely to occur. Third, any "high cost" new initiatives would also have to be examined. The reason for this last point is to avoid the criticism that "While it might be true that you reduced those burdens, you have significantly increased the burden in these other areas, and so I am not convinced." Dealing with this last criticism should not be difficult. It should be relatively straight forward to identify new initiatives that are particularly burdensome and then determine if these additional burdens are greater than the benefits (reduced burdens) previously identified. 4.4 Maximizing Net Benefits The most ambitious goal of the government's regulatory policy has to do with maximizing benefits to Canadians (i.e., not only are benefits greater than costs, the benefits are maximized in comparison with costs). As mentioned in the previous chapter, simply measuring the costs of regulation is a significant undertaking. A further problem resides in the fact that there is no consensus about the "cost" of regulation to the Canadian economy. Given the current state of our knowledge of costs it is likely to take several years before a reasonable estimate of costs is known. (RAD is currently sponsoring a study on the cost of regulation and this should shed some light on what a credible and precise estimate of the cost might be.) Thus any demonstration that benefits are greater than costs and indeed, are as great as possible, for all regulation will take some time. In the absence of convincing evidence for the regulatory system as a whole, a sensible approach would be to show that for some significant set of existing regulations benefits exceed costs. One would like to show that the benefits are at a "maximum" over costs. Doing so, requires (at a minimum) cost/benefit data for the actual situation and acceptable estimates of alternative versions of the regulatory regime (i.e., to demonstrate that the actual situation is the "best" of the feasible alternatives). Formally, this comparison would require caring out a modified benefit cost study. One would not examine all benefits and all costs of all regulation but simply look at the major initiatives (both for decreases and increases in burden). This study would require an explicit statement about why each case was chosen for analysis and why other cases were not included (to avoid criticism that one has chosen the cases to support the point). Choosing the sample is a difficult issue which needs to be addressed. Since the long term-impact of RAD is to be on "greater prosperity for Canadians" the choice of regulations to review needs to reflect their likely impact on prosperity. Unfortunately "prosperity" has a number of meanings and requires some further operational definition. 11 MANAGING BETTER Number 16 While most people might accept the idea that prosperity can be measured in economic terms (i.e., as the cost of regulatory burden is reduced, the prosperity of Canadians will be increased ) some will argue that reduced costs, if they increase poor health is not what was intended. 4.5 A World Class Regulatory Regime There are two different ways that recognition of Canada's regulatory regime as world class could take place. First, Canada could be recognized by "knowledgeable experts" (e.g., through the use of a structured series of scales) as having a world class regulatory regime. Second, if Canada's regime is world class (i.e., sensible and appropriate for the times we live in) then RAD should have some influence/effect on other governments. This influence might be most evident inside Canada (e.g., with provincial governments) but it could occur with other governments and or intergovernmental organizations. One challenge facing those trying to measure the impact of government sponsored initiatives is the difficulty of being trapped within a particular country (in this case Canada) with no assurance that it is possible to compare what is going on outside of the particular Canadian initiative. One way to address this problem would be to compare Canada's initiatives (largely embodied in the activities of RAD) with those of a small group of other countries. This would be similar to a "best practices study" which could be carried out in two ways. The simplest way would be to have a group of knowledgeable experts rank/assess RAD's approach along with that of other countries. A second approach would be to have one person (or at least a small study team) carry out a comparison of the existing regulatory regimes of other countries. Such a study would be facilitated by the imminent publication of an OECD study which compares the regulatory regimes of OECD countries. If the chapters on other countries are as detailed as the existing draft chapter on Canada then much of the ground work for the study will have been prepared. Over the longer term these activities (for example, participation at the OECD) should produce important benefits for Canadians and Canada. Measuring these benefits may in some cases be relatively straight forward. For example, if RAD (and the Government of Canada) convinces another government to adopt goal oriented regulation and this directly helps Canadian exports then the benefits may be easy to measure. The more difficult problem will be to determine the extent to which the changes can be attributed to the activities of RAD. Were the changes inevitable and encouraged to only a small extent by RAD or was the shift in emphasis heavily influenced by RAD? Deciding how much of the change to attribute to RAD will be difficult but some thought should be given to examining such impacts. Unfortunately, these impacts are likely to occur over the longer term (i.e., not in the first five years of RAD's existence). There may be concrete examples within Canada that can be examined in the short term. The five evaluation issues and the concepts/indicators that might be involved in their study 12 Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform are presented in Appendix A. Additional information (in support of the overall evaluation of RAD) can come from regulatory review reports and from the review activities within departments. For a variety of reasons while these are likely to provide some additional help (for example if an evaluation or audit of a regulatory program is carried out) gathering this information together will not in and of itself allow RAD to measure how it is doing in any overall sense. For example, it will not allow RAD to address the question of improvements (or perhaps ongoing improvements) to the "regulatory culture" within departments. In addition, the review activities of departments are likely to be exhibit a great deal of variability and fragmentation, especially when viewed from the perspective of RAD. 5. Options In the previous chapters we have described the activities of RAD and identified the main impacts and long-term benefits. To assess the performance of RAD Chapter 4 sketches five issues that could be studied over the next two to three years. All of the issues can be studied in the sense that no insurmountable barriers exist to their being examined. The study of a world class regulatory regime (issue 5) and its associated intergovernmental impacts has as its most difficult problem that of determining the extent to which RAD contributed to the change (in technical terms, the degree of attribution). Since the other government is obviously not under the direct influence of RAD it is unlikely that all of the change could be attributed to RAD, although it could be the case that some substantial portion of the change could be attributed to RAD. One challenge would be to show the evidence in support of a strong attribution in such a way that it would be convincing to an outside observer. This may be difficult and is probably the strongest argument against carrying out such a study. Perhaps a sensible compromise would be to design such a study and then determine if it can be carried out in a convincing manner. The other four issues can be successfully studied. The easiest issue to study is change in the regulatory culture since it mainly involves a survey of the regulators and the regulated. Regulating smarter and changes in regulatory burden can also be readily studied, but can only convincingly be studied if there is some comparison over time. To do so require much more attention in terms of design (there are some tricky design issues). In particular both studies require careful definition of certain key terms (e.g., what do we mean by intelligent regulation, burden and so on). While one's first sense is that the definition problems are not difficult it is important to remember that one is attempting to measure items for which standard questions (and or scale items) have not been commonly used. Both studies if carried out properly would probably be the first studies of their kind in the world. The study of benefits (are benefits maximized over costs?) while not conceptually difficult poses some interesting challenges in its execution. A number of difficulties have already been mentioned (e.g., the absence of any agreement about the current cost of regulation). Addressing gaps in our knowledge (and resolving technical matters) will take time and 13 MANAGING BETTER Number 16 resources. The extent of progress on this issue will have a substantial impact on the extent to which this issue can be studied. At a minimum case studies of key sectors should be possible. (This may be all that is possible.) While the five issues can be studied there are, however, considerations of timing and scope that need to be addressed. There are two factors that need to be considered in any discussion of the schedule one might use to carry out the necessary studies. First, when would RAD like to have the information and second, when can the information be collected (i.e., when can the required studies be carried out)? 5.1 Schedule RAD would like to have (some) information on its effectiveness for mid 1997 and additional information (as complete as possible) by late 1998. To produce objective and independent information for these two times an evaluation of RAD would have to be divided into a series of studies that while carried out independently, could be integrated in such a way that taken as a whole they address significant aspects of the work of RAD. Thus the work carried out for 1997 has to be designed/developed in such a way that it can be included in (or contribute to) the studies completed for 1998. A second consideration supports such an approach. Some of the measures required (e.g., costs vs. benefits) require time to be assembled, and in almost all cases will have to be studied by sector (e.g., transportation, health, agriculture). This suggests that the overall evaluation must be divided into a series of "case studies" that address immediate impacts of RAD. However, the "case studies" need to be designed in such a way that they can be integrated into an overall evaluation. An example of the types of questions one would like to be in a position to answer are described in Appendix B. (a) Scope of the Evaluation While it is possible to meaningfully address the five evaluation issues identified in Chapter 3, a number of subjects need to be considered before an evaluation is begun. Three of the main factors are: i. the need to consider a number of research initiatives that are completed, ongoing or planned (e.g., there are three OECD initiatives which could materially contribute to the evaluation), ii. the sectors to be examined (e.g., is the evaluation to look at all sectors or only those sectors represented by the seven key departments?), and iii. progress on the study of the "costs of regulation." Only when answers are available for these questions can one decide on the final scope of the study. 14 Performance Framework for the Assessment of Regulatory Reform 5.2 Options One way to approach the options for the study would be to look at choices among and between the studies. This is probably a fruitless task until the studies have been carefully thought through and been subject to a design and scoping study (much as one might complete a scoping study before examining the costs and benefits of a project). Exhibit 1 presents an ambitious, but feasible, schedule for carrying out the necessary work. This might be thought of as the most feasible option. Options (i.e., variations on Exhibit 1) essentially involve the scope of the work to be done. Decisions about scope should be made when the proposed studies have been designed and costed. At this time it is not possible to estimate study costs. EXHIBIT 1 Feasible Option Framework - 1996 Design Studies - 1996 1st quarter Mid Year 1. Culture 2. Smarter Regs 3. Burden 4. Costs/Benefits 5. World Class Recognition Interim Report Final (Integrated) Report Deliverable 1996 15 1997 1998