case description - Namibian Society of Physiotherapy

advertisement

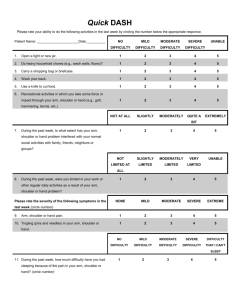

MOBILISATION WITH MOVEMENT FOR PAIN AND STIFFNESS AFTER BANKART REPAIR: A CASE REPORT B. Burmeister A Case Report submitted to the Orthopaedic Manipulative Therapists’ Group of the South African Society of Physiotherapy, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Continuing Education Course in Orthopaedic Manipulative Therapy (OMT course). Windhoek September 2010. MOBILISATION WITH MOVEMENT FOR PAIN AND STIFFNESS AFTER BANKART REPAIR: A CASE REPORT Coded Number: ……………. A Case Report submitted to the Orthopaedic Manipulative Therapists’ Group of the South African Society of Physiotherapy, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Continuing Education Course in Orthopaedic Manipulative Therapy (OMT course). Windhoek September 2010. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..............................................................................................3 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................2 CASE DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................4 DISCUSSION ........................................................................................................... 10 CONCLUSION .......................................................................................................... 15 REFERENCE LIST .................................................................................................... 16 ABSTRACT Shoulder pain is a common phenomenon in the general population and physiotherapists are often challenged by the complexity of shoulder conditions. Manual therapy is known to be a useful tool in the management of shoulder pathology. It was the objective of this study to assess the value of Mulligan’s MWM in a painful and stiff shoulder after a Bankart repair. The treatment technique used was a sustained anterior-posterior glide of the humerus, maintained by the therapist while the patient performed a previously impaired active gleno-humeral movement. Pain intensity, range of movement (ROM) and functional disability were used as measurement outcomes and assess by means of the numeric pain scale, goniometer and the SPADI questionnaire respectively. A significant initial impact on the pain intensity was achieved after three treatment sessions. The active ROM for external rotation increased by 30 degrees, abduction improved by 70 degrees and flexion by 35 degrees within four to five treatments. The functional disability changed dramatically form a score of 48% prior physiotherapy intervention to 2.31% after the sixth session. The amazing results indicate that this specific MWM technique had an immediate effect on pain, ROM and function, and is certainly a useful technique in manual therapy. Further research is required to evaluate the mechanism by which this occurs and other areas of application, since only limited literature is available. Key Words: Mobilisation with Movement, Bankart repair, Shoulder pain, Shoulder stiffness 1 INTRODUCTION Shoulder disorders are a common source of pain in the general population with reports mentioning a prevalence of 30% of the population experiencing shoulder pain at some stage in their lives (Lewis 2008). Shoulder dislocations were found to be a frequent phenomenon affecting approximately 1,7% of the population of the United States and Sweden. Anterior dislocations were the most frequent type of dislocation (95%) and usually seen in individuals aged between 18 to 25 years with an incidence ratio of 9:1 male-to-female. The mechanism of injury for anterior dislocation was mostly traumatic in nature and recurrence rates were found to be approximately 80% to 94% in people younger than 20 years at the time of initial dislocation. The major pathology in the age group 18 to 25 years was believed to be a Bankart lesion (Wilson and Price 2009). The gleno-humeral joint, a so-called ball and socket joint, consists of the convex humerus articulating on a very shallow glenoid fossa deepened by a cartilaginous rim, the labrum. A tear to a specific part of the labrum, the inferior gleno-humeral ligament, is called a Bankart lesion. This type of lesion can be managed conservatively by immobilisation and physiotherapy, or surgically in case of recurrent dislocations, where the torn labrum is reattached to the anterior margin of the glenoid to restore its normal position. This procedure is referred to as a Bankart repair, and is done by open or arthroscopic means or used in conjunction with a capsular shift procedure where the anterior joint capsule is tightened selectively to optimise tension in the anterior capsulo-ligamentous complex (Cluett 2009 and Millett et al 2005). Although the results of the Bankart repair were usually good, post-surgical stiffness 2 often developed. Millett et al (2005) proposed that although stiffness after surgery for the treatment of open anterior instability was seldom reported on in the literature, the prevalence was probably underreported. Magit et al (2008) found in their study that anterior-posterior gleno-humeral translation was decreased at three and six months post surgery for anterior or posterior instability. Another possible predisposition to joint stiffness was established in a study by Ko et al (2008) revealing that a higher level of a pro-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1 beta, in the shoulder joint was directly linked to a deficit in joint motion. A similar increased production of interleukin1 beta was found in the synovium of gleno-humeral joints with anterior instability (Gotoh et al 2005). Physiotherapists often use manual therapy to treat post surgical stiffness. Mulligan’s mobilisation with movement (MWM) treatment techniques were used in many musculoskeletal conditions to decrease pain and improve range of motion and function (Collins et al 2003, Teys et al 2006, and Vicenzino et al 2006). A technique that De Santis and Hasson (2006) found to be useful involved the application of a sustained anterior-posterior (AP) glide that is maintained by the therapist, while the patient actively performs a painful and/or restricted movement. It was the purpose of this study to investigate the effect of manual therapy using Mulligan’s MWM in the treatment of pain and stiffness after surgery for anterior instability. 3 CASE DESCRIPTION ASSESSMENT The patient was a twenty-eight year old female, who fell off a horse and injured her right shoulder eleven years ago. At the time it was diagnosed as a biceps tear. The right shoulder being her dominant side remained troublesome and she received an injection into the joint a month later .She dislocated her right shoulder for the first time while lifting up a blanket onto her horses’ back about six months after the initial injury. Since then frequent dislocations had occurred over the past ten years. Approximately one month before surgery, she fell down the stairs at work, where she was employed as personal secretary, and dislocated her shoulder yet again. After this incident she was unable to continue with her daily horse-riding programme due to pain and the risk of further trauma. She was concerned that she would not be able to ride again or participate in her other sporting activities- cycling and running. This led her to the decision to have a surgical repair done. An open Bankart- repair and a capsular shift were done on her right shoulder. Physiotherapy treatment started two weeks after surgery and she was treated using active and passive physiological movements. At a follow-up consultation with the surgeon, he found her progress to be unsatisfactory and she was referred to our practice for further management. She arrived eleven weeks after surgery and on assessment, her main complaint was very limited active range of movement (ROM) of the gleno-humeral joint, accompanied by pain at the end of ROM. Functionally, she was unable to wash her back and experienced great difficulties opening a car door, washing her hair, placing an object 4 onto a high shelf, reaching her back pocket and carrying heavy objects of about 4 kg. In her work environment she struggled to maintain the expected performance level due to her abovementioned main complaints. Her social life was only affected to a minor extent, but she had not been back to riding yet, fearing dislocation or re-injury. Observation revealed that her right scapular was elevated and retracted. Muscular atrophy on the right side was noted when compared to the other side. On assessment of the active physiological movements of the right gleno-humeral joint, flexion was limited to 120 degrees due to stiffness and abduction was measured at 60 degrees causing pain of an intensity of 6/10 at the subacromial area (pain area 2). External rotation and extension were limited to 0 degrees and 30 degrees respectively due to an anterior joint pain (area 1) of an intensity of 6/10. The right hand behind back movement could reach to the middle of her right buttock. The evaluation of the passive physiological movements resulted in the same clinical findings as for the active movements. The muscle power in the right upper arm was established at a grade 3 to grade 4+ using the Oxford Scale. For the purpose of the above assessment the goniometer was use to measure ROM and the numeric pain scale to determine the intensity of the perceived pain. Both of these are acceptable means in the clinical setting (Riddle et al 1986; Williamson and Hoggart 2005). At the first visit the patient completed the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index questionnaire and scored a total SPADI score of 48%. This questionnaire was found to be useful in patients where movement of the shoulder is encouraged (Heald et al 1997). There was no indication of any neural sensitivity. The patient’s general health was good. She used an anti-inflammatory drug for a week after surgery. 5 Considering the history and examination findings it was hypothesised that glenohumeral joint, ligament and capsular dysfunction were the major components of her shoulder pathology. The anterior capsular tightness was the intended result of the surgery, but could according to Werner et al (2006) affect humeral translation during movement and hence alter the joint kinematics. David et al (2008) found glenohumeral translation to be restricted at three months post surgery for shoulder instability, which corresponds with this study. Body Chart 1 Area 1 Ant gl-h jt Intermittent Intensity 6/10 Sharp - deep Area 2 Lat gl-h jt (subacromial) Intermittent Intensity 6/10 Ache – superficial 6 MANAGEMENT The patient was treated twice a week for three weeks for the duration of about thirty to forty-five minutes each session. The individual session consisted of an assessment of active ROM and pain intensity of specific active physiological movements, the application of the manual therapy technique, the re-assessment of each movement and home exercises. The choice of intervention was Mulligan’s (MWM) using a sustained AP glide of the humeral head maintained by the therapist while the patient performed active glenohumeral external rotation in neutral, abduction or flexion. The treatment procedure and quantity of repetitions were followed as described by Mulligan (1999) for peripheral joint treatment .The individual active movements used were purposefully selected to represent movements that were impaired by one of the three variables, namely, pain in area 1 or pain in area 2 or stiffness only. During all treatment sessions a specific management sequence was followed to ensure consistency. The patient was seated on the edge of the plinth and the active ROM for external rotation (in neutral) was measured and the pain intensity was recorded. Then the MWM technique was applied using external rotation as active movement, followed by measurement and documentation of ROM and pain intensity again. The same procedure was repeated for abduction and flexion. The session was concluded by firstly, teaching the patient home exercises involving active gleno-humeral joint movements using a stick / wall to maintain the gained pain free active ROM and to facilitate joint proprioception and secondly, scapular mobility exercises to assist with the correct scapular position as illustrated in appendix 2. 7 At the end of the sixth session the patient completed a SPADI questionnaire again, and was discharged with an exercise programme, since MWM did not have any effect anymore. (See appendix 2 for programme and questionnaire). OUTCOME The patient responded very well to the Mulligan MWM technique. At each treatment session an increase in active ROM and/or decrease in pain intensity could be achieved. The pain intensity decreased rapidly, while the ROM improved more slowly as illustrated in Table 1 below. Table 1: TREATMENT RESULTS Day 1 Assessment Day 1 Treatment Day 7 Treatment Day 12 Treatment Day 16 Treatment Day 19 Treatment Day 22 Treatment Active Movement Intensity Pain Area Range of Movement Intensity Pain Area Range of Movement Intensity Pain Area Range of Movement Intensity Pain Area Range of Movement Intensity Pain Area Range of Movement Intensity Pain Area Range of Movement Intensity Pain Area Range of Movement Ext Rot 6/10 A1 0º 4/10 A1 10º P2 0/10 Abduction 6/10 A2 60º 2/10 A2 70º P2 0/10 15º P2 0/10 30º P2 0/10 90º P2 1/10 A2 110º P2 2/10 A2 110º P2 0/10 30º P2 0/10 130º P2 0/10 155º S2 0/10 30º P2 130º P2 155º S2 20º P2 0/10 Table 1 Legend: Ext Rot = External Rotation P = Pain S = Stiffness 8 Flexion 0/10 120º 0/10 130º S2 2/10 A1 150º S2 3/10 A1 155º S2 0/10 155º S2 0/10 After six treatment sessions she had overcome her previously experienced functional limitations, the SPADI questionnaire score had changed from 48% to only 2.31% and she had returned to horse riding for an hour per day. A follow-up session at 70 days after the initial visit revealed that she had regained full pain free ROM in all active physiological movements apart from external rotation in 90 degrees of abduction, which was limited by 20 degrees. 9 DISCUSSION The treatment of musculo-skeletal dysfunction often involves the use of manual therapy techniques such as Mulligan’s MWM where a sustained accessory glide to a joint is maintained while a pain provoking movement is performed. The effect of this technique is based on the concept of restoring a’ positional fault’ occurring secondary to injury and resulting in symptoms like pain, stiffness or weakness. It has been suggested that changes in the shape of the articular surface, cartilage thickness and soft tissue alignment or direction of pull could be the cause of a positional fault (Hing et al 2008). Numerous studies indicated that MWM techniques have a beneficial effect on the specific outcome measures used, such as pain levels, ROM, strength or pain pressure threshold (PPT), to mention a few. In this case study the pain intensity, ROM and function were used to evaluate the effect of MWM. An immediate improvement in the pain intensity was found during the initial two treatment sessions. Similar results emphasising the immediate effect were obtained by Teys et al (2006) in a repeated measures, double-blinded randomised–controlled trial with a crossover design, where the initial effects of a MWM technique on ROM and PPT in individuals with anterior shoulder pain were investigated. In osteoarthritic knee joints it was found that accessory knee joint mobilisation caused both an immediate local and widespread hypoalgesic effect (Moss et al 2007). The actual extent of the hypoalgesic effect of MWM in this study was reflected in the vast reduction of the pain intensity decreasing from 6/10 to 0/10 for external rotation and abduction movements within the first two treatment sessions as seen in chart 1. 10 Chart 1: Treatment Results Pain Intensity 10 8 External rotation 6 Abduction 4 Flexion 2 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Treatment Session In an attempt to find an explanation for the actual pain control mechanism involved in the hypoalgesic effect of MWM, Paungmali et al (2004) conducted a randomised, controlled trial to evaluate the effect of naloxone injection on the MWM-induced hypoalgesia. The interesting finding demonstrated that naloxone did not antagonize the initial hypoalgesic effect of MWM, indicating that non-opioid pain inhibiting pathways were involved in the pain control mechanism. It was mentioned that these findings correlated with similar studies involving spinal manual therapy techniques. Further research is required to investigate the precise neuro-physiology behind this pain control mechanism. A study conducted by Collins et al (2003) assessed the initial effects of a MWM technique in sub-acute lateral ankle sprains using dorsiflexion ROM, PPT and thermal pain threshold (TPT) as comparable sign. From the results it could be derived that the MWM technique had a significant immediate positive effect on dorsiflexion ROM only. In this case study it was found that the ROM increased gradually, but consistently during treatment sessions one to five, to the effect of 0 to 11 30 degrees for external rotation, 60 to 130 degrees for abduction and 120 to 155 degrees for flexion, indicating a less dramatic response as shown in chart 2. Chart 2: Treatment Results Degrees of Movement 180 150 120 External rotation 90 Abduction 60 Flexion 30 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Treatment Session Interestingly, a clear difference in the effect of treatment on pain intensity compared to ROM could be seen. The slower, gradual improvement of ROM compared to the fast change in pain could possibly be attributed to the prolonged period of inadequate movement in the gleno-humeral joint prior to the treatment with MWM. Alternatively it could be suggested that the limited ROM could be due to soft tissue tightness rather than a positional fault causing joint dysfunction. Unfortunately, the severely limited ROM in this patient did not allow a proper assessment of possible posterior capsule tightness, which could have thrown light on this issue. It was realized as a shortfall in this case study. The functional impairment of the patient in this case study improved significantly according to the results of the SPADI questionnaire, which changed from 48% to 2.31% after six sessions. A case study by De Santis and Scott (2006) where the same MWM technique was used to treat a patient with subacromial impingement, a 12 similar major impact on function was experienced. Paungmali et al (2003) in a study using MWM for lateral epicondylalgia had the same outcome indicating a positive responds favouring the improvement of function as in pain-free grip force over changes in PPT and sympathoexcitation. From the available literature it was evident that the effect of Mulligan’s MWM techniques was assessed in a variety of spinal and peripheral applications using a wide range of outcome measures. Amazingly, only the case study conducted by Virtuoso et al (2008) was found, where the same MWM technique was used for the same condition as in this case study. The outcome of that study indicated that exercises combined with Mulligan’s MWM had a beneficial effect on ROM and strength. Unfortunately it was not mentioned how soon after surgery the treatment started, which compromises the value of a comparison of the two studies. A different treatment technique that could possibly have a similar effect as Mulligan’s MWM is a technique described by Lewis (2008) called the humeral head procedure. It is part the shoulder symptom modification procedure (SSMP) that he introduced in an attempt to propose an alternative clinical examination method for shoulder impingement syndrome/ rotator cuff tendinopathy. It is based on the same principal as MWM by applying a glide to the head of the humerus. In Lewis’ technique however, the pressure could be applied in one or more directions to the humeral head while the patient performs the activity or movement that most closely reproduces the symptoms. Since only little evidence exits to support this treatment model, further research could reveal interesting information with regard to the effect of MWM compared to SSMP in the treatment of pain and/or stiffness. In other literature describing the common treatment regimes used after shoulder surgery, it was noticed that only Maitland’s mobilizations were mentioned in addition 13 to exercises and other modalities (Turner et al 2000). The value of Mulligan’s MWM and SSMP as part of the post surgery treatment regime for a Bankart repair and other conditions should be assessed in further research. 14 CONCLUSION This study highlights the value of Mulligan’s MWM technique using an A-P glide of the humerus in a painful and stiff shoulder after a Bankart repair. The immediate hypoalgesic effect, and the positive impact on the functional disability and the ROM obtained, supports this. In addition it was found to be useful even in the late stage of rehabilitation where soft tissue tightness was thought to be the cause of glenohumeral dysfunction. Limited literature is currently available, leaving a vast scope for research that could throw more light on the mechanism by which Mulligan’s MWM work, and the value of it in other conditions or in conjunction with other treatment modalities 15 REFERENCE LIST Blackburn TA, Guido JA 2000 Rehabilitation after ligamentous and labral surgery of the shoulder: guiding concepts. Journal of Athletic Training Vol 35 (3): 373-381 Cluet J 2009 Shoulder dislocation with a Bankart tear. About.Com orthopaedics. http://orthopaedics.about.com/cs/generalshoulder/a/bankart.htm?p=1 [Online] re- trieved on 15.05.2010 Collins N, Teys P, Vicenzino B 2003 The initial effects of a Mulligan’s mobilisation with movement technique on dorsieflexion and pain in subacute ankle sprains. Manual Therapy 9:77-82 De Santis L, Hasson SM 2006 Use of mobilisation with movement in the treatment of a patient with subacromial impingement: a case report. The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy Vol 14(2): 77-87 Gotoh M, Hamada K, Yamakawa H, Nakamura M, Yamazaki H, Inoue A, Fukuda H 2005 Increased interleukin-1 beta production in the synovium of glenohumeral joints with anterior instability. Journal of Orthopaedic Research Vol 17(3): 392-397 (abstract) Heald SL, Riddle DL, Lamb RL 1997 The shoulder pain and disability index: the construct validity and responsiveness of a region-specific disability measure Physical Therapy Vol 77(10): 1079-1089 Hing W, Bigelow R, Bremmer T 2008 Mulligan’s mobilisation with movement: a review of the tenets and prescription of MWMs. New Zealand Journal of Physiotherapy Nov 2008 16 Ko J-Y, Wang F-S, Huang H-Y, Wang C-J, Tseng S-L, Hsu C 2008 Increased interleukin-1 beta expression and myofibroblast recruitment in subacromial bursa is associated with rotator cuff lesions with shoulder stiffness. Journal of Orthopaedic Research Vol 26(8): 1090-1097 (abstract) Lewis JS 2008 Rotator cuff tendinopathy/subarcomial impingement syndrome: is it time for a new method of assessment? British Journal of Sports Medicine 43: 259264 Magit DP, Tibone JE, Lee TQ 2008 In vivo comparison of changes in glenohumeral translation after arthroscopic capsulolabral reconstructions. American Journal of Sports Medicine 36(7): 1389-96 (abstract) Millett PJ, Clavert P, Warner JJP 2005 Open operative treatment for anterior shoulder instability: when and why. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 87: 419432 Moss P, Sluka K, Wright A 2007 The initial effects of knee joint mobilisation on osteoarthritic hyperalgesia. Manual Therapy 12: 109-118 Mulligan BR 1999 Manual Therapy “NAGS”, “SNAGS“, “MWMS“ etc. 4 th edn. pp 99102. Plane View Services Ltd, New Zealand Paungmali A, O’Leary S, Souvlis T, Vicenzino B 2003 Hypoalgesic and sympathoexcitatory effects of mobilisation with movement for lateral epicondylalgia. Physical Therapy Vol 83 (4): 374-383 Paungmali A, O’Leary S, Souvlis T, Vicenzino B 2004 Naloxone fails to antagonise initial hypoalgesic effect of a manual therapy treatment for lateral epicondylalgia. Journal of Manipulative Physiological Therapy Vol 27 (3): 180-185 (abstract) Riddle DL, Rothstein JM, Lamb RL 1986 Goniometric reliability in a clinical setting: shoulder measurements. Physical Therapy Vol 67 (5): 668-673 17 Teys P, Bisset L, Vicenzino B 2006 The initial effects of a Mulligan’s mobilisation with movement technique on range of movement and pressure pain threshold in painlimited shoulders. Manual Therapy 13: 37-42 Vicenzino B, Paungmali A, Teys P 2006 Mulligan’s mobilisation with movement, positional faults and pain relief: current concepts from a critical review of literature. Manuel Therapy 12: 98-108 Virtuoso JF, Mosca LS, De Oliviera TP, Sprad F 2008 Physical therapy and Mulligan technique after bankart shoulder injury surgery - a report case. Fiep Bulletin Vol 78 special edn. Article 1 Werner CML, Nyffeler RW, Jacob HAC, Gerber C 2003 The effect of capsular tightening on humeral head translations. Journal of Orthopaedic Research Vol 22(1): 194-201 (abstract) Williamson A, Hoggart B 2005 Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. Journal of Clinical Nursing Vol 14 (7): 798-804 (abstract) Wilson SR, Price DD 2009 Dislocation, shoulder. eMedicine http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/823843 [Online] retrieved on 16-07-2010 18 19