Chapter 1: Introduction

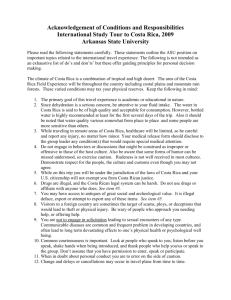

advertisement