Giving Someone a Reason to Φ

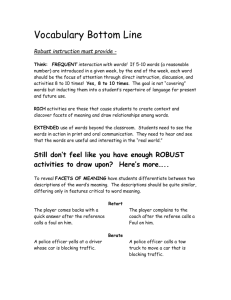

advertisement