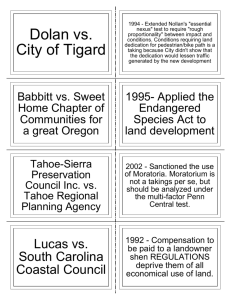

Average Reciprocity of Advantage: 'Magic Words' or

advertisement