In human life, there are many things people think they know with

advertisement

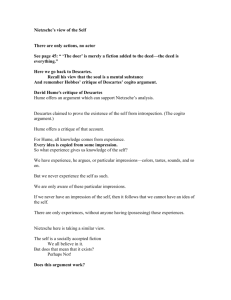

What can I know with certainty, if anything? What is the source of knowledge? What is ‘truth’? In human life, there are many things people think they know with certainty. Is it really so? Can anybody be really sure about knowing something? What make us know something? Is there any knowledge in the world that is so certain that no reasonable man could doubt it? According to Bertrand Russell, this last question, which at first sight might not seem difficult, is really one of the most difficult that can be asked. In daily life, we assume many things to be certain, which after a closer analysis, are found to be less correct than we first thought. Knowledge plays a very important part in human lives. In the history of humankind, it was knowledge that separated common people from the mighty ones. It was the one’s knowledge that evoked respect, power, or fear from others. Today, knowledge is more accessible than ever before. There is an obligatory education system, newspapers, Internet, and scientific journals that are available for everybody and offer all kinds of information and knowledge. But is everything what we learn in school or read on the Internet true? Can I be certain about any knowledge I have gained in my life? It is the theory of knowledge that deals with these kinds of questions, to distinct things between appearance and reality, between what things seem to be and what they are. The technical name for the theory of knowledge is epistemology, which is derived from the Greek word episteme, meaning “knowledge,” and the suffix ology, meaning “science of.” In its original sense the word “science” meant “an organized body of knowledge.” Today, theory of knowledge is an organized body of knowledge about the knowledge. The question about the nature of knowledge became very popular for ancient Greek philosophers who formulated numerous theories concerning it. An important part of the ancient Greek thinker’s philosophies was the concern about the origin and nature of the world. These early thinkers were led to the conclusion that the world is different from what it appears to be. This fact allowed a new series of disputes about the true nature of reality, and these disputes generated extended controversy about the nature of knowledge itself. According to Heraclitus, the world is a thoroughly dynamic system (a “fiery flux”) in which permanence and stability are something of an illusion. He claimed that everything moves on and that nothing is at rest. Parmenides, a contemporary of Heraclitus tried to explain how reality is known, but ended up with an absolutely surprising view of things. According to Parmenides, thought and reality are the same and whatever is, is; and whatever is not, is not. Hence, change cannot occur. A later thinker, Protagoras, turned his back to the idea that there is an ultimate reality behind appearances and argued that our knowledge concerns appearances and nothing else. He asserted that man is the measure of all things, so things that appear to one man may be different to another. Protagoras’ claims seemed false to Plato. According to Plato, “one cannot reasonably claim that all knowledge is relative because in doing so one implies that some of it is not, namely, the knowledge one claims to have.” To allow that the latter knowledge may also be relative is completely self-defeating, since it will also allow the alternative claim of Heraclitus and Parmenides that genuine knowledge is never relative (Aune, 5). Therefore Plato thought that at least some knowledge is nonrelative. In developing his ideas, Plato used the views of Heraclitus and Parmenides. For Plato, the both men were undoubtedly correct in saying that knowledge is nonrelative and concerns the true nature of reality. Heraclitus’s idea that the natural world is constant, throughout going change; and Parmenides’s idea, that true knowledge concerns something eternal and unchanging both impacted Plato’s thinking. To provide his thoughts, Plato used geometry as a model for his theory of genuine knowledge. He argued that circularity, triangularity, and numbers are all know as ideal objects, because they can be fully understood and defined. No drawn circle is a “perfect circle” and things in nature merely approximate the shapes of a perfect circle, therefore mathematical objects, such as the perfect circle, exists only as ideas and may have genuine knowledge. In addition to these ideal mathematical objects, Plato also admitted ethical objects as genuinely knowledgeable as well. Such objects are Courage, Temperance, Piety, and Goodness (Aune, 6). These ethical ideals are also unchanging, eternal and can be exactly understood. On the other hand, the lack of human behavior’s perfection makes genuine knowledge of humans strictly impossible. No man is perfectly good or perfectly courageous and therefore the ethical qualities of human beings are always matters of degree. Like drawn circles, human beings are only partially understandable and our view of them can be characterized only within ideas. It seems hard to believe that theories formulated 2500 years ago could have such a big impact on world of philosophy. Plato and his idea, that true knowledge is restricted to a domain of ideal object and that things in nature are understandable only approximately, gave a good starting point for other subsequent thinkers that based their views regarding man and the world on Plato’s ideas. Although the entire history of philosophy is very fascinating and full of powerful ideas, the “breakthrough” came with the modern period and its father René Descartes. This famous thinker attempted to develop theory of knowledge that would settle philosophical controversy once and for all. He determined that he would believe nothing which he did not see quite clearly and distinctly to be true. He tried to bring everything for himself to doubt and whatever he could bring to doubt, he would doubt, until he found something that can’t be doubted. By using this method he found out that the only thing he could be quite certain about was his own existence. If he is doubting, he must necessarily exist as a doubter, as a being who does the doubting. You cannot doubt if you do not exist, if you doubt, you must exist, if you have any experiences whatever, you must exist. Since he is doubting, he exists; his existence is an absolute certainty to him. “I think, therefore I am,” he said. Descartes has discovered his absolute certainty, and on the basis of this certainty he set to work to build up again the world of knowledge which his doubt had laid in ruins. Descartes performed a great service to philosophy, but his knowledge is on the other hand extremely limited in content. He is certain about his existence whenever he thinks, but he does not know what he is. To facilitate his search for further knowledge Descartes attempted to identify the distinguishing features of an indubitable truth. He did this by focusing on the certain knowledge that he had discovered. He found that his certainty about his existence amounts to no more than a clear and distinct apprehension of his existence. Apprehension of this kind must, therefore, be a certain mark of truth; if his apprehension of something would go wrong, he could not be certain about his own existence. Therefore, whatever can be apprehended very clearly and distinctly must be true. Descartes’ approach to knowledge is a good example of what is called epistemological rationalism. The term rationalism is applying to theories of knowledge similar to that of Descartes. Taking Descartes as a representative, our knowledge of reality is an organized structure based on a foundation of certain truth. The certainty of this truth is known immediately, intuitively, and is indubitable. So known truth occurs in two kinds: general principles and particular matters of fact. The truth of general principle include such certainties as thinking requires a thinker; the truth of particular matters of fact include such specific intuitions as one has the idea of perfect being. All other knowledge, including knowledge dependent of use of our senses, is derivative from these basic certainties. If Descartes can be taken as a representative for rationalism, than Hume can be the representative for empiricism. Unlike Descartes, Hume believed that human knowledge could be ascertained only by the development of the “science of man,” which would exhibit a man’s thought process and his reasoning. Hume obtained Isaac Newton’s idea of using experimental method for developing the “science of man.” Hume claimed that “the only solid foundation we can give to this science itself must be laid on experience and observation.” (Aune, 40) These words could be identified as the motto of all following empiricisms. The empiricists maintained that all our knowledge is derived from experience, while rationalists maintained that in addition to what we know by experience there are certain ideas which we know independently to our experience. According to Hume, a man’s mind consists of impressions and ideas. Impressions comprise our raw experiences – desires, emotions, feelings and they give rise to ideas. He describes his theory on the example of pain. A man feeling pain can recall the memory of this pain less vivid and there is a considerable difference between the perception of the mind during and after the pain occurred. Our immediate, raw experience differs from our thoughts in being more vivid and forceful. According to Hume, “our thoughts may mimic or copy our impression, but they never can reach the force and vicacity of the originals.” (Aune, 41) According to these discoveries, Hume distinguishes simple from complex ideas. Hume assumed that simple ideas build complex ideas by the means of “compounding, transporting, augumenting, or diminishing.” The thought that all complex ideas can be analyzed into simple ideas, these simple ideas are copies of impressions helped Hume to identify that a posteriori knowledge is gained through experience based on our memories and senses. To know something, we first need to experience it or observe it. Some philosophers held the idea that whatever exists, or whatever can be known to exist, must be in some sense mental. This basic principle forms the grounds of idealism are generally derived from the theory of knowledge where things must first satisfy some conditions in order to know them. Bishop Berkeley was the first philosopher that attempted to establish idealism on such grounds. He proved that our sense data cannot exist independent of us and must be, at least partially, ‘in’ the mind. Sense data would not exist if there were no seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, or tasting. He argued that our perceptions could only guarantee the existence of things that are immediately known in sensation, and that to be ‘in’ mind means to be known, and therefore to be mental. Hence he concluded that only what is in mind can be known and everything outside the mind can never be known, and that whatever is known without being in somebody’s mind must be in somebody else’s mind. For Berkeley, anything that is immediately known, such as things immediately known in sensations, are called ‘ideas’. For example, seeing a particular color is an idea. He shows that all we can know about perceiving common objects, such as an apple, consists of ideas, and he argues that there is no reason to suppose that there is anything real about the apple except what is perceived. He states that its being consists in being perceived, and he admits that the apple continues to exist even when we are not looking at it or when we leave the room where the apple is situated. This continued existence of the apple is due to the fact that God still perceives it and the apple consists of ideas in God’s mind, and stays there as long as the apple continues to exist. According to Berkeley, all our perceptions consist in partial contribution in God’s perceptions, and because of this perception different people perceive the same apple but with little differences. It is hard to say which philosopher is right in his proposal of a theory of knowledge. Everybody sees certain problems from different points of view and with different attitude. If I should state what I think is the correct theory of knowledge, I would borrow ideas from all of the mentioned theories. I would take Berkeley’s idea and say that to know something we need both, our senses, to identify the aspects things, and our mind, to “explain” the aspects of things and connect them together to build an actual object from theses aspects. But this would allow things to exist only in the present moment, because our senses capture the data of a certain object only in the time we are in contact with it. Therefore, I would use Hume’s idea of impressions and ideas, which states that our knowing is based on our experience, thus we must first observe a thing and store it so we can later recall it and so know it. Descartes’ theory “I think, therefore I am” shows me that things other than myself must also exist. Because Descartes stated this, he must exist. I think, therefore I am. If Descartes and I exist, and Descartes and I are the same kind of things, then other kind of things like us must exist. If different existing people can observe the same thing, then this thing exists for them. Somebody could argue that two different people observing a thing at the same time actually don’t observe the same thing because they don’t describe the thing in the same way. I think this might be the cause of different expressions, not different perceptions or different interpretations. It is because people’s definitions of things are very simple and reserved. The question of knowing things is a really difficult part of philosophy. Knowing that a physical object, such as table, is situated in the middle of a room, we achieve two kinds of knowledge about it: knowledge of things and knowledge of truths. Knowledge of things can be achieved by acquaintance, which is essentially simpler than knowledge of truths and also logically independent of knowledge of truths. Knowledge of things can be known by description and is dependent on some knowledge of truths. We can say that we have acquaintance when we are directly aware of things. In the table example, I am acquainted with the appearance of the table that is immediately known to me through sensation, like when I am touching or seeing the table. Thus, seeing the color of the table doesn’t make me know the color itself any better than I did before. I have acquaintance of the things immediately known to me just as they are, but not the table itself. The knowledge of the table is further known only by describing the table by means of the sense data. This is called the knowledge of description, and in order to know anything about the table, we must know truths connecting it with things which we are acquainted. Thus, all our knowledge about the table is knowledge of truths, and we do not know the actual table at all. The only thing we know is that there is an actual object to which the description applies, but this object is not directly known to us. As things are concerned, we may know them or not know them. Our knowledge of truths, unlike our knowledge of things, has an opposite side, called error. We may conclude wrong inferences from our acquaintance, but the acquaintance itself cannot be delusive. Unlike the knowledge of truths, for acquaintance there is no dualism. We may believe what is false as well as what is true. As long as many people hold different beliefs and opinions, some of them must be erroneous. So how do I know that my opinion is not erroneous? According to Bertrand Russell, this is a question of the very greatest difficulty, to which no completely satisfactory answer is possible. How can we know whether a belief is true or false? There are three points, which states an attempt to discover the nature of truth. A true theory of truth: (1) allows truth to have an opposite, namely falsehood, (2) makes truth a property of beliefs, but (3) makes it a property wholly dependent upon the relation of the beliefs to outside things. How can we know what is true and what is false? How can we know anything at all? Can we say that knowledge could be defined as true beliefs? If my belief is true, can I concluded that I have achieved knowledge of what I believed? To give an example, I can guess and say that you own a red Ferrari car. I can be right, and you really own one, in spite I had no idea what kind of car you really own. Can I therefore conclude that I have certain knowledge, because I knew that you have a red Ferrari car? A true belief is not always knowledge. A true belief cannot be called knowledge if it is deduced from fallacious reasoning, even if the belief’s premises are true. To know something, the premises must not only be valid, but must also be known. Therefore, we can say that knowledge is what is validly deduced from known premises. Philosophy’s goal like most other studies is primarily knowledge. The knowledge it seeks is the kind of knowledge, which gives unity and system to the body of sciences. The kind, that results from a critical examination of our convictions, prejudices, and beliefs (Russell, 154). The real value of philosophy is its very uncertainty. Philosophy is unable to tell us with certainty what the true answer is, but through our questions and doubts, it suggests many new ways and possibilities. Therefore, philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions, but rather to for the sake of the questions themselves. Works cited: Aune, Bruce. Rationalism, Empiricism, and Pragmatism. New York: Random House, 1970. Nagel, Ernest, and Richard B. Brandt. Meaning and Knowledge. Harcourt, 1965. Russell, Bertrand. The Problems of Philosophy. Oxford University Press, 1959. Moore, Brooke Noel, and Kenneth Bruder. Philosophy, the Power of Ideas. McGraw-Hill, 2002.