Educational Guidance in Human Love (1983)

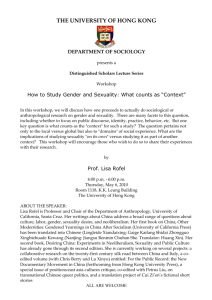

advertisement