Martin Buber on Dialogue in Education and Art

advertisement

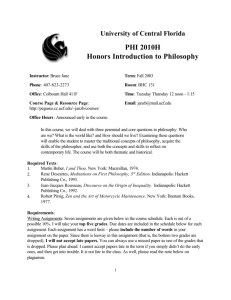

Martin Buber on Dialogue in Education and Art. By: Shtelman Rina The Kaye Academic Educational College , Beer-Sheva, Israel In his essay “Education” written in 1925, Martin Buber states that: “What we term education, conscious and willed, means to give decisive selection by man of the effective world: it means to give decisive effective power to a selection of the world, which is concentrated and manifested in the educator. The relation in education is lifted out of the purposelessly streaming education of all things, and is marked off as purpose. In this way, through the educator, the world for the first time becomes the true subject of its effect.”1 The concern of the educator, while educating, should be remaining a true mediator, a selector, and a giver of direction. This should be done through real dialogue, responsibility, and faith. The model for such education “remains the classical master, through him the selection of the effective world reaches the pupil”.2 In the same article Buber states that: “Art is then only the province in which a faculty of production, which is common to all, reaches completion. Everyone is elementally endowed with the basic powers of the arts, with that of drawing, for instance, or of music; these powers have to be developed, and in education of the whole person is to be built up on them as on the natural activity of the self.” 3 1 Thus the connection between art and education is a natural one, given the fact that all of us humans are born with a capacity of creative powers demonstrated through creative activities in the domain of art, from early childhood. However, the relation between education and art, described in Buber’s article suggests that creativity and art creations are different capacities, upon which education can be based. In Martin Bubers' words the relation between art and education when educating is sometimes an I-It relation. But education itself has to be based upon one’s whole and true self, meaning, upon dialogical , I-Thou relations. In his major ontological work, I and Thou, Buber explains how people relate and what are the forms of relating in the world. Buber also explains at length what is the meaning of rue dialogue, the kind of dialogue that is essential during educational processes. Buber points out that the world is twofold for every person, in accordance with one's twofold attitudes. Each attitude accords with a primary word. One primary word is the combination I-Thou, the other is I-It. The I-It attitude and the relations, which spring from it, govern most human concerns in everyday life. In dealing with these concerns a person is usually not relating with one's entire being. Buber states clearly that the I-Thou is spoken with one's whole being; in contrast the I-It is never spoken with one's whole being. He writes: “I perceive something. I am sensible of something. I imagine something. I will something. I feel something. I think something. The life of human beings does not consist of all this and the like alone. This and the like together establish the realm of it. But the realm of Thou has a different basis.” 4 2 The different basis to which Buber refers is established because, when the word Thou is spoken, the speaker stands in relation with one's whole being to one's partner in the relationship. One is fully present to the Thou. The I-Thou relationship and its basis can be pointed to, but not analyzed. Buber points to three spheres in which such a relationship comes into being: life with nature, life with other persons, and life with spiritual beings. A person who endeavors to open oneself to the possibility of relating with one's whole being, as a Thou, may find partners in each sphere. But one's endeavors, persisting as they may be, cannot ensure that an I-Thou relationship will come into being. As Buber often repeated in I and Thou:” The Thou meet me in a moment of grace”. In the sphere of nature Buber describes relating with one's whole being to a tree. In the human sphere he described I-Thou relations in great detail. In the sphere of spiritual beings Buber relates to art. He writes that in creating a work of art, a person speaks the primary word, Thou, with one's entire being. And it may happen, that as the effective power of this speaking of the artist streams out, the work arises as a worthy artistic creation, its beauty becomes manifest. In I and Thou Buber does not describe how a spectator relates to a work of art, nor the way to educate towards art. But his writings intimate that in relating to paintings and sculptures say, a spectator can encounter and be addressed by the Thou that the artist's being has spoken when he or she created the work of art. Important challenges facing educators can be concluded from here; one of them is to indicate how to base the education of the whole upon the creative capacities that we are born with. The second conclusion, is how to approach the doing of art as a partner in an IThou relation, and the third is to consider the possibility of encountering a work of art as a Thou . The educator should suggest ways by which the pupil can educate oneself to be open to these moments of grace in which the beauty of a work of art may address him or her as a 3 Thou. Yet, indicating such a possibility abstractly, by merely explaining Buber's thought, will not necessarily bring students to live in a manner those accords with Buber's insights. Explaining Buber is frequently like explaining art academically, pointing out only the ideas and missing a complete fulfilling. Explaining often appeals to the understanding and only in a general manner, if at all, to one's mode of existence. Instead of an immediate encounter with Buber's insights, the explanation frequently mediates between the person and Buber’s thinking. Furthermore, in relation to art, explaining may often cloud the immediate encounter with, say, a painting, by diverging the student's attention from what addresses him or her in the painting and directing him only to the ideas explained. Thus, when a teacher relies on explaining art, rather then educating towards experiencing the painting or the sculpture. Only very rarely, such an approach will lead to a personal change in the way of life of the student, which may alter his or her manner of creating and relating to art, or towards creativity. Buber states that: ” This is the eternal origin of art that a human being confronts a form that wants to become a work through him. Not a figment of his soul but something that appears to the soul and demands the soul’s creative power. What is required is a deed that a man does with his whole being: if he commits it and speaks with his being the basic word to the form that appears, then the creative power is released and the work comes into being.”5 Without going into details about Buber’s ontology, it is evident that he believed that the origin of art, and the relation between man and true art creation is a relation of I-Thou. 4 The domain in which man creates and relates to art is the spiritual domain. Buber explains that during the release of creative actions, the deeds involve sacrifice and risk. Sacrifice is pictured as the infinite possibilities surrendered on the altar of form, and risk as the commitment of being able to speak only with one’s whole being. During creating art, man can not seek “relaxation in the It-world”, meaning that while creating art the artist has to struggle and give his whole self. Not serving properly or holding back part of himself becomes ruinous, for the artist and his creation. From this brief passage it can be discerned that, like the educator, the artist is also a selector, a selector of forms and possibilities. The artist has to relate with his whole self, while molding his idea into the material, shaping his idea into forms, or sounds, or verses. He has to relate truly to himself, the world and the form he is creating. He has to give a true direction to the world. Even though, creating of art seems a subjective act, a lonely individualistic act as put by Buber in “Education”, the relation underlined by Buber’s philosophy is an I-Thou relation. And once again, a true I-Thou relationship engages dialogical relations, partnership, authenticity not only between people, educators, and pupils, but also in the spiritual domain, including art. From this definition and distinction, we can discern that a link to art and art education emerges. Relating to art, as discussed briefly above, seems similar to relating dialogically to a partner in a relationship of genuine dialogue. In confronting a work of art or the actual making of a work of art, I must strive to relate with my whole being to the whole being of that specific work of art. Buber’s thinking seems to indicate that persons who can relate dialogically to other persons, who address other persons as possible partners in genuine dialogue, will find it easier to relate to art with their whole beings. More so, the choice and ability of a dialogical way of life are common components in the task of education, art, and art education. 5 The educator must be very much aware that the possibilities of such an encounter are diminished if one imposes one's views on the student. Consequently, the art educator must learn to bring the students to meet works of art, and not to strive to have them understand works of art or to imitate them. Thus, a dialogical person who approaches a work of art will not merely seek to understand the painting, or to obtain aesthetic pleasure. Rather, the dialogical person approaches the work knowing that perhaps one will be able to share a new direction opened up by the work of art, and experience the beauty inherent to such sharing. Buber's thought instructs us that a change of one's way of life is often needed so as to change one’s perspectives on life on creativity and on art. Put succinctly, Buber calls us to live what he termed a life of dialogue, which, he believed, will greatly enhance the possibility of meeting the Thou in our daily encounters. A teacher who strives to live a life of dialogue and educates accordingly, or a student, who is open to live a life of dialogue, will frequently be much more open to change one's way of relating to the world to men and to art. Such an educational approach requires showing ways to being open to other beings that may encounter one as a Thou. Being open to the possibility of encountering the Thou, Buber believes, must emerge in one's everyday existence. In the “Elements of the Interhuman”6 Buber articulated pertinent suggestions that can help the educator guide one's pupils to relate and live dialogically. Thus, to open themselves to the possibility of encountering the Thou. Buber opens his essay "Elements of the Interhuman"7 with a distinction between the social and what he calls the realm of the interhuman. Buber believes that this latter realm has been very much ignored in discussions of human interactions. Genuine or real dialogue and I-Thou encounters can only occur in the interhuman. In the social realm persons relate to each other as Its, as members of organizations, institutions or other groups. In the realm 6 of the interhuman, persons relate to each other as partners that are united in the world by their relations. Some conclusions emerge when relating towards art: a. relating to a painting or to a sculpture as a call to partnership in molding the world is a way of engaging the work of art and relating to it wholly, without seeking explanations. In such an engaging, the viewer responds to the work of art as to a unique expression of the artist. The viewer is sometimes addressed as a partner who is invited to partake in the beauty that he has created. When one responds thus to a painting or a sculpture there is a greater probability that one can relate as a Thou or as a partner in dialogue to this painting. Striving to establish an I-Thou relation in the realm of the interhuman or the spiritual realm of art, engages education that is based upon dialogue and true partnership. Dialogical education enhances the possibility of sharing between partners in dialogue. Dialogical partnerships are essential in establishing faith between educators and students. When such a partnership is established in the realm of art, for instance, between the viewer and the work of art, there is a possibility of its beauty emerging and resounding in one's being. Thus, it is us who are responsible for establishing the partnership in the beauty that flows to us viewers from all great works of art. Buber's distinction between being and seeming are connected with authenticity and falseness. Being and seeming are of major significance for the educator who wishes to guide one's pupils to relate dialogically, to persons or to other beings, including works of art. Buber writes: “We may distinguish between two different types of human existence. The one proceeds from what one really is, the other from what one wishes to seem. In general, the two are found mixed together. There have 7 probably been few men who were entirely independent of the impression they made on others, while there has scarcely existed one who was exclusively determined by the impression made by him. We must be content to distinguish between men in whose essential attitude the one or the other predominates.”8 In order to live a life of dialogue in which I relate to the other who confronts me as a partner in dialogue, Buber explains, I must strive to eliminate all seeming from the relationship. I must endeavor to relate to that other spontaneously, without reserve, as a possible genuine partner, not as an object to be manipulated by the impression that I wish to make. In the above citation Buber pointed out that it is almost impossible to totally free oneself from seeming. But he calls upon each reader to persist in striving to relate in accordance with one's being. He added that relating with one's being to the other often requires much courage, and self education. Such is the courage to live straightforwardly, to seek a life of dialogue and to bring truth into being. In the relationships that I establish: "Whatever the meaning of the word truth may be in other realms, in the interhuman realm it means that men communicate themselves to one another as what they are."9 Let me underline the conclusions mentioned before: The educator who wishes to educate one's students while giving them a true and worthy direction in life has to strive to live and relate dialogically himself... Striving to relate dialogically enhances the possibility of educating towards dialogical relation between people, towards nature, and towards the spiritual realm including works of art and art making. Buber would add that the educator who daily struggles to live straightforwardly and to eliminate all seeming from his or her relationships with one's students is directing towards the path that leads to a life of dialogue. The dialogical educator will also guide towards relating to art personally and authentically. 8 The educator can advise each one: You must approach each specific work of art with your being, without trying to make any impression upon anyone. You must turn to the work of art spontaneously, without reserve, with the truth of your being. The same accords to the teacher who strives to teach how to make art, how to bring forward the pupils unique and true abilities. The teacher must be careful with his explanations about how to bring forward his pupils true and authentic ideas. The educator has to lead his students in such a manner that, creation will be the result of performing his or her choices out of free will, and free from “seeming”. A “true selector of directions” as Buber wrote in “Education”, educates towards dialogue between the art student his idea and the material he is handling. However rare these moments are manifested, they will always be landmarks in the educational processes of art teachers. When showing, say, William Turners’ “Snownstorm – Steamboat Off a Harbour’s Mouth”10, the educator can add: I must be very careful with what I say. Joseph Mallord William Turner. "Snowstorm-Steamboat off a Harbor's Mouth". Oil on Canvas. 324 on 241 inch, Tate Gallery, London 9 My explanations may divert you, as a viewer, from relating to this painting by Turner spontaneously, from encountering it as an address by the painter who has generously shared his ability to bring forth beauty in this painting with you. I must add here that the same applies, when an art teacher explains precisely how to draw or paint a harbor or a steamboat, or when literature or, poetry are taught. Relating with one's being to other persons, Buber stresses, requires retaining the innocence that is at the basis of all genuine dialogue. The educator's role is to appeal to the innocent gaze of the student and to help the student guard this innocence when he or she encounters art. Furthermore, Buber instructs us specifically in his article “Education”, to build upon the “instinct of origination”, which is unique to every child, pure without being directed by having but only by doing. This originating power, Buber explains, is at the basis of wanting to create something new, in shape and form, from materials around us. Children are born with this capacity, and it is the duty of educators and teachers to guard and cultivate this potential in its pure and true form. Educators are encouraged by Buber to build upon these powers during educative processes: “This instinct is therefore bound to be significant for the work of education as well. Here is an instinct which, no matter to what power it is raised, never becomes greed, because it is not directed to “having” but only to doing; which alone among the instincts can grow only to passion, not to lust; which alone among the instincts cannot lead its subject away to invade the realm of other lives. Here is the pure gesture which does not snatch the world to itself, but expresses itself to the world.” 11 10 For instance, Buber demonstrates this attitude in his article “Education”, by pointing out two possible ways to teach art in the classroom. “Let us take an example from the narrower sphere of the originative instinct - from the drawing-class. The teacher of the compulsory school of thought began with rules and current patterns. .. You knew what beauty was, and you had to copy it; and it was copied either in apathy or in despair. The teacher of the “free” school places on the table a twig of broom, say, in an earthenware jug, and makes the pupils draw it…or he tells the pupils to look at it, removes it, and then makes them draw it…..soon not a single drawing will look like another. Now the delicate, almost imperceptible and yet important influence begins – that of criticism and instruction. The children encounter a scale of values that, however unacademic it may be is quite constant, knowledge of good and evil that however individualistic it may be is quite unambiguous.” 12 One teacher, he says, will come into the class and with the set of academic rules will deprive the students of the chance to choose freely. This kind of teaching will intervene in the natural faculties of creativity that wait to manifest and illustrate themselves through the work of art. In other words academic rules have the power of effacing the pupil's spontaneity. The same situation occurs when a teacher or instructor tries to explain works 11 of art in a museum for instance. I can show the two paintings "The Violin and Guitar” painted by Picasso: Pablo Picaso. "The Violin and Guitar". 319 on 425 inch Paris. 12 George Braque." Les Jour". 350 on 272 inch, oil on canvas.Paris. Or the painting "Les Jour by George Braque, to my students, wishing to encourage them to relate with innocence to the paintings.13 To help them retain their innocence, I should refrain from adopting any kind of strategy. I must accept this innocent gaze, even if it leads the student to not appreciate or to reject the beauty of both of these paintings. I can only suggest to the student who rejects these paintings to return to the paintings and view them again and again. Perhaps after looking and trying earnestly and wholly to really see more, one's response will change. 14 The other example, pointing towards a free approach as Buber puts it, enables the students to make free choices, and express a spointain approach, carried out authentically. Criticism and instruction are important, but they have to be encountered after 13 the creative performance occurred. That is the way, Buber explains to encounter a scale of values. The more unacademic this scale of values and the more individualistic this knowledge will be, the deeper will be the encounter. The formal approach, which supposes in advance what is right by the teacher, leads to assignation and rebellion. In the latter more freer example, where the pupil gains the realization only after he has ventured far on the way to his achievement, reverence for form and education are drawn in the pupil’s heart.. These examples portray important and day to day experiences during educational sessions in art classes. What Buber is underlying here are the educational values that can be transferred to other educational cases that are not necessarily connected with art performances. Educators can learn that relating authentically, while giving the pupil the possibility of relating freely can lead towards a meaningful learning. Let me repeat that such relations are usually based upon what Buber explains is called genuine or real dialogue. Buber indicates that, for genuine dialogue to occur between two persons, each of the two must endeavor to personally “make present" one's partner.15 Thus, if I wish to be open to the possibility of genuine dialogue, I must be fully present to this specific person whom I encounter, and endeavor to relate to him or her as a possible Thou, unique in his or her individuality. Buber adds that making present is essential in dialogical partnerships. Once again, true dialogical partnerships are not behavioral patterns but a way of life, and that is the link to what Buber calls the classical master, meaning education as a way of life and not only a profession. From I and Thou it is evident that such dialogical relating, such making present, can frequently guide persons to relate to other persons or to works of art in a manner that will enhance their existence. Buber explains that a true educator is a giver of true direction, meaning that he distinguishes between imposing oneself on one's students and helping them unfold themselves. Here is the explanation: 14 “There are two basic ways of affecting men in their views and their attitude to life. In the first a man strives to impose himself, his opinion and his attitude, on the other in such a way that the latter feels the psychical result of the action to be his own insight, which has only been freed by the influence. In the second basic way of affecting others, a man wishes to find and to further in the soul of the other the disposition toward what he has recognized in himself as the right... The other need only be opened out in this potentiality of his; moreover, this opening out takes place not essentially by teaching, but by meeting”...16 Buber believes that propaganda is the primary method of imposing, and dialogical education is a manner of encouraging unfolding. Advertisement for instance is an aggressive manner of imposing. Imposing one’s views and desires in order to further financial or personal interests is a method of aggressive imposement and manipulation. Many persons often find it difficult to discern the truth in the flood of propaganda those daily streams toward them, seducing them to follow the imposter of views and desires to wherever he or she wishes to lead them. Using uniform methods or patterns during educative sessions, and clinging to them year after year, without considering the students in front of you, is manipulative. Such is also the case when teachers try to seduce their pupils rather then to meet them in a genuine dialogical meeting. Ultimately, faith between teachers and students, 15 that is essential in any educative process, can be built only upon dialogical and I-Thou relationships. Art has also become subject to these degrading developments. Thus, works of art are often related to as if they were consumer goods, whose merit is attaining an outstanding price at art auction. And, such can happen during creative classes, when art is approached only as a mean to further other prospects then the development of creative potential, by the teacher. However, what Buber suggests, I believe, given the fact that men are born with the present of artistic creativity, this domain can be related to, in different ways. As Buber explains in “Education”, there are times when art activities become educational devices. In those cases the educator can rely on creative faculties as means that have the ability to lead towards unfolding and bringing forth new and fresh ideas. In this case the relation between education and art will be a day to day I-It relation. In those cases we try to build upon the spiritual domain in order to empower the interhuman. Even though it is suggested that “let us learn from one domain in order to enhance the other”, which seems positive and legitimate educational activity, art is not being related for its own sake, during those sessions. Art is not being approached dialogically, but rather as a mean for developing another area. In summery, during the creating of art, during educating towards art or, relating towards a work of art, the relation has to be a dialogical I-Thou relation. During the task of character education, education has to be approached as a work of art and the relation between educator and pupil has to be based only on the I-Thou relationship. But it seems that there are times when the domain of education is based upon the creative inner powers of man. In those cases, education is manipulating creativity for its own purposes. The dialogical truths that are enlightened by Martin Buber’s writing concerning education and 16 art are existential. As Buber would have said: during most human concerns, in everyday life, relations are mostly governed by I-It attitudes. Even Education and Art can sometimes become or switch to I-It relations. But, persons, who endeavor to open themselves to a dialogical way of life, relating as a Thou, may find partners in each sphere. Such are worthy relations and worthy ways of living in the world. List of Illustrations “Snowstorm – Steamboat Off a Harbor’s Mouth”– Joseph Mallord 1. William Turner. 19th century. (Tate Gallery, London). 2. “Guitar and Violin” – Pablo Picasso.319 0n 425 inch. ( Paris). 3. “Les Jour” – Georges Braque. 350 on 272 inch. (Private Collection, Paris). 1Martin Buber. Between Man and Man .“Education”. Boston: Beacon Press, 1955. P.89. 2---------------- Ibid.p. 90 3---------------- Ibid.p. 84 4 Martin Buber, Thou, Trans. Ronald Gregor Smith and I. (NewYork: Collier Books, 1987) p.4. 5----------------. 6Martin I And Thou . (Translated by Walter Kaufmann).New York: Touchstone, 1970. P.60. Buber, The Knowledge of Man, “Elements of the Interhuman” (New York: Harper and Row, 1965) 7 Ibid, pp. 72-88. 8 Ibid. pp.75-6. 9 Ibid. p.77. 10One can see this painting in: Jay Jacobs The color Encyclopedia of World Art (the Tate Gallery, London), pp.284-285. 11Martin Buber, Between Man and Man, “Education “, Trans. Ronald Gregor Smith. (Boston, Beacon Press, 1955) p. 86. 12----------------, 13 Ibid. p.88 One can see both these paintings in William Rubin, Picasso and Braque: A Symposium. The Museum of Modern Art, New-York. pp. 50, 85. 14Gordon Haim and Shtelman Rina. “A Buberian Educational Approach to Cubist Art”, the Journal of Aesthetic Education. Vol. 34 no. 1. Spring 2000. p. 97-113. 15 Martin Buber, The Knowledge of Man., “Elements of the Interhuman” (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), p78. 16 Ibid. p. 82. 17 18