Humanistic Psychology Handout

advertisement

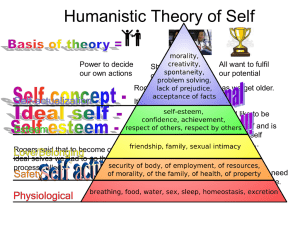

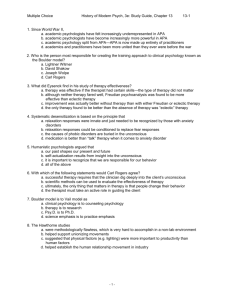

Humanistic Psychology THE THIRD FORCE While the first half of the twentieth-century was dominated by psychoanalysis and behaviorism, a new school of thought known as humanistic psychology emerged during the second half of the century. Often referred to as the “third force” in psychology, this theoretical perspective emphasized conscious experiences. American psychologist Carl Rogers is often considered the founding father of this school of thought. While psychoanalysts looked at unconscious impulses and behaviorists focused purely on environmental causes, Rogers believed strongly in the power of free will and self-determination. Psychologist Abraham Maslow also contributed to humanistic psychology with his famous hierarchy of needs theory of human motivation. Where did it come from? During the 1950s, humanistic psychology began as a reaction to psychoanalysis and behaviorism, which dominated psychology at the time. Psychoanalysis was focused on understanding the unconscious motivations that drove behavior while behaviorism studied the conditioning processes that produced behavior. Humanist thinkers felt that both psychoanalysis and behaviorism were too pessimistic, either focusing on the most tragic of emotions or failing to take the role of personal choice into account. Humanistic psychology was instead focused on each individual’s potential and stressed the importance of growth and self-actualization. The fundamental belief of humanistic psychology was that people are innately good, with mental and social problems resulting from deviations from this natural tendency. In 1962, Abraham Maslow published Toward a Psychology of Being, in which he described humanistic psychology as the “third force” in psychology. The first and second forces were behaviorism and psychoanalysis respectively. However, it is not necessary to think of these three schools of thought as competing elements. Each branch of psychology has contributed to our understanding of the human mind and behavior. Humanistic psychology added yet another dimension that took a more holistic view of the individual. The person-centred approach The person-centred approach is so called because, as we have seen above, humanistic psychologists place a person’s subjective experience and subjective point of view at the very centre of their theories. Rogers and Maslow regarded personal growth and fulfillment in life as a basic human motive. This means that each person, in different ways, seeks to grow psychologically and continuously enhance themselves. This has been captured by the term actualization or self-actualisation which is about psychological growth, fulfillment and satisfaction in life. Carl Rogers and the fully functioning person In common with other humanistic psychologists, Rogers believed that every person could achieve their goals, wishes and desires in life. When they did so self-actualisation or self fulfillment took place. Characteristics of a fully functioning person Characteristics Open to experience Existential Living Trust feelings Creativity Fulfilled life Description Both positive and negative emotions accepted. Negative feelings are not denied, but worked through. In touch with different experiences as they occur in life; avoiding prejudging and preconceptions. Feelings, instincts and gut-reactions are paid attention to and trusted. Creative thinking and risk taking are features of a person’s life. Person does not play safe all the time. Person is happy and satisfied with life, and always looking for new and challenging experiences. Evaluative Point The fully functioning person represents and ideal state, and probably one that is never achieved by any person. Critics may claim that the fully functioning person is a product of western culture and represents an individualistic and selfish approach to understanding what human beings are about. In other cultures, such as eastern cultures, the achievement of a group of people may be valued more highly than the achievement of any one person. Self – Worth and Positive regard How we think and feel about ourselves, our feelings of self-worth are of fundamental importance both to psychological health and to the likelihood that we can achieve goals and ambitions in life. Self-worth may be seen as a continuum from very high to very low. For Rogers (1959) a person who has high self-worth faces challenges in life, accepts failure and unhappiness at times, and is open with people. A person with low self-worth may avoid challenges in life, not accept that life can be painful and unhappy at times, and will be defensive and guarded with other people. Rogers believed that childhood experience influences how future interactions with people and achievements are perceived. He stated that children have 2 basic needs: Unconditional positive regard from other people Positive self-worth Unconditional positive regard is where parents and significant others accepts and loves the person for what he or she is. Positive regard is not withdrawn when the person does something wrong or makes a mistake. The consequences of positive regard are that the person feels free to try new things out and make mistakes, even though this may lead to getting it wrong at times. People who are able to self-actualise are more likely to have received unconditional positive regard from others, especially their parents in childhood. Self-worth is often seen as a continuum, from very high to very low and is the confidence a person has in themselves and their ability. For Rogers, a person who has high selfworth has the confidence to face life’s challenges and accept failure and unhappiness at times. Self-Concept and Congruence/Incongruence For Rogers, the self-concept has two aspects. The first is self-worth. The second is our ideal-self, which is our conception of how we should be in all aspects of our life, work, relationships, feelings of fulfilment, etc. A person’s ideal self may not be consistent with what actually happens in life and experiences of the person. Hence a discrepancy or difference may exist between a person’s ideal self and actual experience. This is called incongruence. Where a person’s ideal self and actual experience is consistent or very closely aligned a state of congruence exists. When incongruence is high the person may find it difficult to adjust and live a happy life. High incongruence would reflect many aspects of a person’s life differing greatly from their ideal. When incongruence is low, or congruence is close, then a person is likely to be satisfied and fulfilled with life. A person with a high level of incongruence may suffer psychological distress, and may find it difficult to adjust and live effectively in society. Client-centred and person centred therapy Rogers called his therapeutic approach client-centred or person-centred therapy because of the focus on the person’s subjective view of the world. Rogers regarded everyone as a ‘potentially competent individual’ who could benefit greatly from his form of therapy. Person-centred therapy operates according to three basic principles that reflect the attitude of the therapist to the client, theses are: 1. The therapist is congruent with the client. 2. The therapist provides the client with unconditional positive regard. 3. The therapist shows empathetic understanding to the client. The purpose of Rogers’ humanistic therapy is to increase a person’s feelings of selfworth, reduce the level of incongruence between ideal and actual self, and help a person become more of a fully functioning person. Later in his career Rogers moved away from one-to-one therapy and became more involved with group counselling. He developed what he called encounter groups in which people could feel safe and free to express feelings and explore problems in their lives. An encounter group would be facilitated by a Rogerian therapist and operate according to the three principles described above. Evaluative Comment Sexton and Whiston (1994) reviewed a large number of research studies that had been conducted to find out just how effective CCT or counselling is for people. They found that generally the three principles of therapy did result in positive personality changes and successful outcomes for clients. However, they also reported that success was not inevitable and that much may depend on the personality of the client. It was found that clients who became very involved in the process saw their therapists as more helpful than clients who were more detached from the process. The problem with most of these studies is that effectiveness is based on what clients say rather than any objective measure of better functioning and adjustment to life. Another criticism of these studies is that there is not usually a long term follow up of clients