February 1, 2005

Nature's Way:

Behind a Food Giant's Success: An Unlikely Soy-Milk Alliance

At Dean Foods, CEO, Buddhist Team Up to Sell Silk Brand; And Gain Clout in Organics

Mr. Engles's Lesson on 'Sukha'

By JANET ADAMY

Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

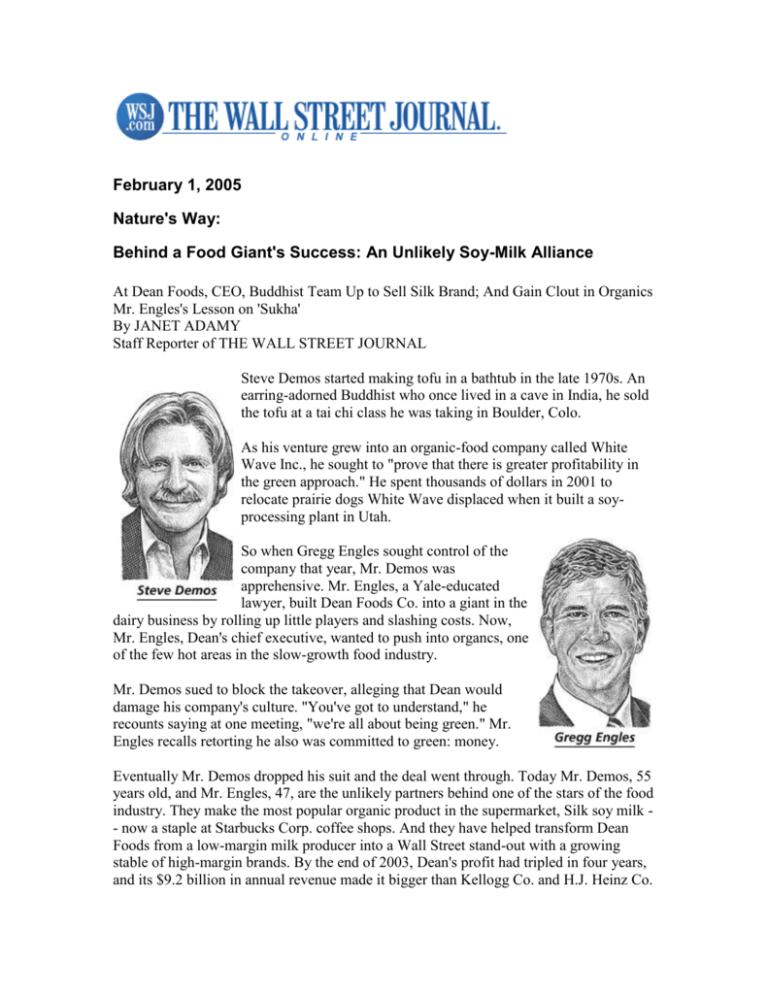

Steve Demos started making tofu in a bathtub in the late 1970s. An

earring-adorned Buddhist who once lived in a cave in India, he sold

the tofu at a tai chi class he was taking in Boulder, Colo.

As his venture grew into an organic-food company called White

Wave Inc., he sought to "prove that there is greater profitability in

the green approach." He spent thousands of dollars in 2001 to

relocate prairie dogs White Wave displaced when it built a soyprocessing plant in Utah.

So when Gregg Engles sought control of the

company that year, Mr. Demos was

apprehensive. Mr. Engles, a Yale-educated

lawyer, built Dean Foods Co. into a giant in the

dairy business by rolling up little players and slashing costs. Now,

Mr. Engles, Dean's chief executive, wanted to push into organcs, one

of the few hot areas in the slow-growth food industry.

Mr. Demos sued to block the takeover, alleging that Dean would

damage his company's culture. "You've got to understand," he

recounts saying at one meeting, "we're all about being green." Mr.

Engles recalls retorting he also was committed to green: money.

Eventually Mr. Demos dropped his suit and the deal went through. Today Mr. Demos, 55

years old, and Mr. Engles, 47, are the unlikely partners behind one of the stars of the food

industry. They make the most popular organic product in the supermarket, Silk soy milk - now a staple at Starbucks Corp. coffee shops. And they have helped transform Dean

Foods from a low-margin milk producer into a Wall Street stand-out with a growing

stable of high-margin brands. By the end of 2003, Dean's profit had tripled in four years,

and its $9.2 billion in annual revenue made it bigger than Kellogg Co. and H.J. Heinz Co.

Dean Foods' stock price has more than doubled since January 2000, far outstripping the

food industry average.

While total food sales are growing by about 3% a year, organics are surging by about

20%. Dean's rivals, coveting that $10 billion U.S. market, have been snapping up organic

brands. Organics now account for more than 5% of Dean's sales and are among the

company's fastest growing products. Along the way, Mr. Engles learned some Buddhist

principles and Mr. Demos earned some new big-business management chops.

As the competition moves into Dean's market, the company faces some tough new

challenges. Dean doesn't have a track record as a branded food company, and it is facing

competitors who do. For example, General Mills Inc.'s 8th Continent soy milk is also

posting double-digit sales growth and threatening to narrow the gap against market-leader

Silk. The last Silk ad campaign didn't increase sales as much as Mr. Demos had hoped.

Last year White Wave's sales grew 31%, shy of Mr. Demos's goal of 36%.

In the late 1980s, Mr. Engles made his first mark in business by assembling a collection

of more than 30 packaged-ice companies. He grew skilled at boosting their margins by

cutting costs. He thought the milk industry was ripe for a similar consolidation. In 1993,

Mr. Engles bought Suiza dairy of Puerto Rico for $106 million. From Suiza's new Dallas

headquarters, he acquired over the next several years more than 50 dairies accounting for

about one-third of the nation's milk supply.

Mr. Engles's biggest deal came in 2001 with the $1.5 billion purchase of Dean Foods. At

the time, Dean was buying other smaller dairies, too, but it wasn't as adept as Mr. Engles

at making its purchases into winners. Mr. Engles felt he could do better. He moved

Dean's headquarters to Dallas from suburban Chicago, but kept the family name of the

founders.

As part of the deal, Mr. Engles got a toehold into White Wave, Mr. Demos's soy

company. Dean had previously invested $15 million in White Wave, with an option to

buy the rest.

It was an intriguing opportunity. The Food and Drug Administration had concluded soy

protein could help people avoid heart attacks and allowed companies to advertise this

claim. Mr. Engles's own effort to market soy milk hadn't gone well, in part because Mr.

Demos got off to an earlier start. So he didn't hesitate when he got the chance to gain

control of White Wave. "This was an underappreciated business," Mr. Engles says.

Mr. Demos took a roundabout route into business. He studied philosophy and political

science in the late 1960s and spent four years traveling through Europe, the Middle East

and India, learning about Eastern philosophy. In India, he says, he lived in a cave for

several months to meditate and practice yoga.

After his Boulder tofu venture started to take off, he kept his hands in all aspects of the

business. He came to the office one New Year's Eve and climbed into a waste-collecting

pit to unclog it. He kept coveralls handy so he could fix food-making machines. He

describes himself as a "benefic dictator" who told workers, "We're doing this, don't ask

questions."

In 1996, Mr. Demos came out with Silk. At that

point, most soy milk was sold in "brick pack"

boxes that sat on store shelves because it wouldn't

spoil in those packages. Mr. Demos put a fancy

logo on a paper carton that required stores to stock

it in the dairy case, where shoppers were more

likely to be looking for milk products.

Mr. Demos tinkered with the taste and slapped on a

heart-healthy label. But he needed more capital to

expand from health-food stores to mainstream

supermarkets, which charge suppliers hefty

"slotting" fees to put their products on shelves. He

approached Coca-Cola Co., Kraft Foods Inc. and

others for money. Dean Foods bit, buying an initial

25% of White Wave in 1999 for $5 million.

White Wave's sales continued soaring as grocery shoppers increasingly reached for foods

grown without pesticides or genetically modified seeds. As a milk substitute, Silk also

appealed to Asians and Hispanics, who for genetic reasons can have trouble digesting

milk in adulthood.

In 2001, Mr. Engles flew to Boulder and told Mr. Demos that Dean wanted to exercise its

option to buy the rest of White Wave for $154 million. Mr. Engles said Dean would give

White Wave access to manufacturing capacity and stay out of Mr. Demos's way. Mr.

Demos was polite but noncommittal.

Two months later in June 2001, Mr. Engles received a fax from Mr. Demos saying White

Wave had sued to block the Dean purchase. Mr. Demos says he never thought the old

Dean management believed in the potential of soy products, and he didn't trust Mr.

Engles to treat him better.

Mr. Engles pressed ahead. He had seen that other big food companies also were buying

organic food companies for their sales potential and wider profit margins. By the

beginning of the decade, food giants such as Kraft and General Mills had bought all or

part of more than a dozen natural and organic food companies.

After a judge ruled against his lawsuit, Mr. Demos prepared to leave White Wave.

Former owners of food start-ups are rarely kept on in management after a takeover, but

Mr. Engles wanted Mr. Demos to stay. He thought Mr. Demos, who owns a farm with

180 organic fruit trees, had keen insight into potential soy consumers. For instance, he

was impressed by how Mr. Demos had engendered brand loyalty by touting the benefits

of pesticide-free farming on Silk packages.

Mr. Engles flew back to Boulder. He

boosted the price by about $40 million and

offered Mr. Demos and his managers an

additional $30 million in incentives to hit

sales targets for Silk. He promised to keep

White Wave's headquarters in Boulder. Mr.

Demos became president and "head bean" of

Dean's White Wave subsidiary.

Mr. Engles quickly approved a $22 million

advertising campaign to keep Silk's sales

growing and a $30 million plan to add soy

extraction facilities to boost Silk production.

Last summer, Mr. Engles sat down with Mr.

Demos and other White Wave folks to craft

a

mission statement for White Wave. Mr. Engles wanted it to spell out the company's focus

on creating shareholder value and high-end brands. Mr. Demos wanted it to embrace

"right livelihood," a Buddhist concept for work that is ethical and beneficial to a person's

spiritual development. Someone in the meeting expressed concern that the term could be

linked to an extremist group.

Having read up on Buddhism himself, Mr. Engles came to the rescue. He explained the

principles of right livelihood to the group, using Hindi words like "dukkha" (suffering),

and "sukha" (happiness) to show the concept wasn't radical. The statement eventually

used "responsible livelihood." Mr. Engles says writing it "was one of the most rewarding

things I've done in business."

Mr. Demos pushed to create a vitamin-enriched children's version of Silk. When Dean

officials in Dallas asked for data showing demand for such a product, Mr. Demos said he

had none, but, "there wouldn't be an opportunity if there was data trending," he recalls.

Dean launched the product in June. Mr. Engles also agreed to spend $350,000 to convert

White Wave's operations to run on wind power.

A big breakthrough came in 2003, after Mr. Demos asked Starbucks to make Silk its

exclusive soy milk. Mr. Demos offered to create a blend that would complement espresso

and chai drinks. The coffee chain accounts for a small fraction of White Wave's revenue,

but the alliance has given the Silk brand valuable exposure.

Silk easily surpassed the sales targets Mr. Engles had set. Its sales are on track to reach

$414 million this year. White Wave now controls about 65% of the dairy-case soy-milk

market, which doesn't include restaurants and Wal-Mart stores, according to Information

Resources Inc., a research firm in Chicago. Last year, Dean paid Mr. Demos an $11

million bonus.

In August, Mr. Engles named Mr. Demos to run Dean's new, $1.2 billion brandedproducts division, White Wave Foods Co. That more than doubled the amount of

business Mr. Demos oversees. Along with Silk, he's now also responsible for Hershey's

chocolate milk, Horizon Organic milk and International Delight flavored coffee creamers.

White Wave has been the most successful organic food purchase in the industry, says

Eric Katzman, a food industry analyst at Deutsche Bank. "They allowed this entrepreneur

to thrive within a decentralized business model," Mr. Katzman says.

After several years of focusing on plain, vanilla and chocolate soy milk, White Wave is

trying to extend the Silk brand with new products and sales venues. The company is

pushing a variety with additional calcium for pregnant women and an unsweetened

version.

White Wave is putting soy-milk vending machines in public schools to capture the

children's milk market. The number of consumers who drink soy milk is "still quite small

looking at the long-term potential," Mr. Katzman says. Industry experts have speculated

that Dean Foods might try to sell or spin off Silk and other brands. Mr. Engles declined to

comment. Last week, Dean said it will spin off its $700 million pickle and private-label

foods business.

In 2003, Mr. Engles joined Mr. Demos at a natural-products trade show in Washington.

There, Mr. Demos introduced Mr. Engles to Ziggy Marley, a musician and son of the

reggae legend Bob Marley. Before Mr. Marley's performance at the show, the three

toured the trade fair together, sampling natural foods. Mr. Engles attended the concert

afterward.

"Steve has definitely caused me to think differently and more thoughtfully about certain

aspects of the business," Mr. Engles says.

After watching Mr. Engles's management, Mr. Demos has started to delegate more. He

lets others write White Wave's quarterly report to the Dean board, a task he'd largely

handled himself. "He's certainly mellowed," says Pam Mettler, White Wave's information

technology director.

Last summer, Mr. Engles and Mr. Demos hit a sticking point on who would research and

develop new products. Mr. Engles wanted credentialed food scientists who were

classically trained in flavor chemistry and other specific disciplines. Mr. Demos wanted

at least one beanie-wearing chef who would propose unconventional new foods. "Wasn't

that soy milk not too long ago?" he argued. The pair compromised by designating one

position for a creative trend-spotter among the team of traditional food scientists.

In June the two men and their wives enjoyed a five-hour dinner in Paris on a business

trip. After a few glasses of wine, Mr. Demos apologized for suing Mr. Engles when he

first tried to buy his company.

Write to Janet Adamy at janet.adamy@wsj.com1

URL for this article:

http://online.wsj.com/article/0,,SB110721282326041634,00.html

Hyperlinks in this Article:

(1) mailto:janet.adamy@wsj.com

Copyright 2005 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. Distribution and use of this

material are governed by our Subscriber Agreement and by copyright law. For nonpersonal use or to order multiple copies, please contact Dow Jones Reprints at 1-800-8430008 or visit http://www.djreprints.com/.