MaryReger

advertisement

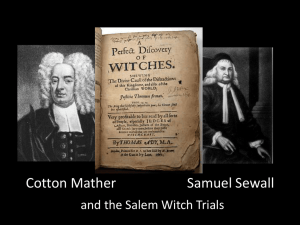

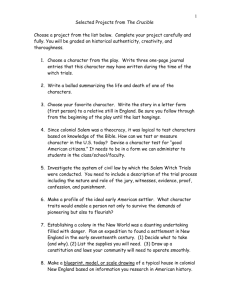

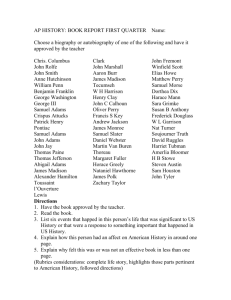

Salem Witch Judge: The Life and Repentance of Samuel Sewall by Eve LaPlante A Book Review by Mary Reger March 2009 Eve LaPlante’s Salem Witch Judge: The Life and Repentance of Samuel Sewall provides insight into important aspects of both New England colonial history and the Salem Witch Trials. The book provides historical, religious, and political insight into the time period of the Salem Witch Trials, which helps to understand LaPlante’s discussion of Sewall and his participation in the Trials. Written by the sixth great-granddaughter to Samuel Sewall, the book offers a personal insight into why Samuel Sewall sought forgiveness for his part in the Salem Witch Trials. LaPlante begins the book with Samuel, as she refers to him, at the age of 31 taking care of his sick newborn baby while his wife Hannah sleeps. She develops Samuel’s character as a loving and devoted husband, father, and friend. She wants the reader to know Samuel in depth before the Salem Witch Trials so that they will understand his heart and grief. Samuel was a deeply religious Puritan man who loved God and desperately wanted to be forgiven for any sins he had committed throughout his life. Samuel had deep roots in New England. His grandfather had come in 1634 and settled and farmed in the coastal town of Newbury, about 30 northeast of Boston. However Samuel’s parents returned to England before Samuel was born in 1652. He lived in England until he was nine years old when his family returned to Newbury. Samuel was a very learned man; he read and wrote Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. He graduated from Harvard College with a Master’s degree in divinity. Although he never practiced in the ministry, he led a very pure life, reading the Bible daily and teaching from it to his family. Samuel found comfort in singing the Psalms when he wanted to celebrate and grieve. In 1676, Samuel married Hannah Hull, the daughter of one of the wealthiest men in Boston. Because Hannah was the only living child of John Hull, Samuel and Hannah moved in with her father so that Samuel could be John’s heir. Samuel very quickly became a prominent figure in Boston. He was an assistant to the court, the captain of the local militia, and eventually became a judge of the court. These were just a few of his titles. Samuel was a kind-hearted and earnest man who knew nearly everyone in Boston, both rich and poor. Hannah and Samuel had fourteen children of which only five grew to adulthood. Only three of his children outlived him. Because Samuel believed in the original sin of Adam and believed himself to be a sinner, he often wrestled with the fact that maybe he lost so many of his children because of his or Hannah’s sins. Samuel loved his children dearly and found it very difficult every time one of them died. Not only does LaPlante do an excellent job of acquainting us with Samuel and who he was but she also gives a thorough history of the Boston area along with the politics and religion in Boston. She explains in detail the court system and religious structure in Boston thus giving the reader vital information for better understanding the mentality of the people at the Salem Witch Trials. She not only focuses on Boston and the events happening there but she includes major issues going on in the world throughout Samuel’s life. While the Salem Witch Trials are going on the French and Indians are attacking towns in northeastern New England causing fear and anxiety in the Boston area as well. She also gives the history of England and its royal leaders as they are related to Boston and New England’s political and religious structure. Only four of the chapters in the 20 chapter book cover the Salem Witch Trials. While the Salem Witch Trials is the pretense for the book being written, it is not the focus of the author’s thesis. LaPlante builds the story to show that her sixth great grandfather was not a witch hunter and that this one small event in his life did not stain his character. She writes the story of families, towns, and a country to show who this man was and to prove that he was a Christian man who strived his entire life to be a good man and a follower of Christ. She shows how he dealt with the guilt of sending 20 people to their death. Samuel felt so badly about this that in 1697, five years after the Salem Witch Trails ended, he publicly repented for having sat on the court that sentenced them to death. Because Samuel did not want to forget the agony he felt he wore a hair shirt under his clothing. Christians wore hair shirts when they felt it would help them to resist temptations and to show bodily mortification of sins committed. LaPlante does not stop at Samuel’s repentance to show his sincere and repentant character but goes on to describe the rest of the events in his life, especially his concern for equity, fairness, and Christ’s love for mankind. Even though New England was in the midst of a war with the French and Indians Samuel helped two Indians go to Harvard College. He also wrote an essay in 1697, titled Phaenomena quaedam Apocalyptica ad Aspectum, wherein he tells his belief in the godliness of the Indians and America. He also did not believe in slavery and he himself never owned a slave even though many people in Boston did. In 1700, Samuel wrote the first antislavery tract published during the period, titled The Selling of Joseph, A Memorial. At this time in history Samuel had no supporters; in fact people thought he was crazy when they read his essay. Samuel was constantly reading scripture and searching his own soul. While one of his daughter’s was on her death bed he thought about the role of women on earth and in Heaven. Puritans believed that only men would be resurrected. This bothered Samuel and he searched the Bible for answers to his questions and wrote another essay titled, Talitha Cumi, in which he argued that women as well as men would be resurrected. LaPlante goes into great depth to show that Samuel Sewall in fact was one of the most Christian men of his time. She showed how he did not follow the wrong doings of others just because it was an accepted practice and that he also put himself out on a limb in his thinking of equality of all man (and woman) kind. She was able to tell an accurate story of this man and his world by not only using numerous secondary sources but also important primary sources from the archives in and around Boston, including histories of the towns, grave marker inscriptions, Samuel Sewall’s papers, essays, and diaries. Published primary sources such as diaries of several people, court records, sermons, psalms and hymns, and political records, were also used. The book itself included a couple of maps of the New England area, psalms that Samuel sung, a couple of paintings, Samuel’s signature in his Indian Bible and the essays that Samuel wrote. These sources were helpful in understanding and being able to relate to the history and story. LaPlante also includes a chronology of Samuel’s life and a genealogy chart that shows the line from Samuel to LaPlante. These helped in keeping the dates and people in order for easy reference. It was very engaging to be able to read through the essays that Samuel actually wrote after reading about his life. LaPlante wrote in such detail that the reader feels as if she personally knew Samuel. The one detail that LaPlante lacked was citations. There were times when I would like to have known where particular information could be found. Although the book is rather scholarly, LaPlante being the acclaimed author of American Jezebel, she wanted to attract a wider audience which would not be as interested in specific notes. LaPlante also brings the reader into the book with a note about the text and an introduction. In the notes on the text she explains how dates were different at the time of history, how names were changed, and how other abbreviations were used. In her introduction she explains Samuel’s repentance honestly and tells her background and relationship to the story and how the story came about in her family, all useful information to have before reading the story. This book is quite different from other books that revolve around the Salem Witch Trials. While The Salem Witch Trials might be a point of interest to attract the reader to this book, the lessons of soul searching, forgiveness, humility, civil rights, and humanity, are the focus in Samuel Sewall’s life. A more in-depth account of the actual practice and history of witchcraft and the school of thought revolving around witchcraft and the Salem Witch Trials can be found in A Delusion of Satan by Frances Hill. The Salem Witch Trails; A Day-By-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege by Marilynne K. Roach is an excellent detailed reference source of people and events during the actual Salem Witch Trials. Another book that looks specifically at the women who were accused of witch craft is The Devil in the Shape of the Woman by Carol F. Karlsen. Figures of the Salem Witch Trials by Stuart A. Kallen is another brief, easy-to-read book that focuses on the major persons at the witch trials, including Samuel Sewall. I would definitely recommend this book to anyone who would like to know more about New England Colonial history and specifically about Boston and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. LaPlante organizes her chapters clearly and chronologically, often going back in time to provide more background so the reader has a better understanding of the whole picture. Because this book does not make the Salem Witch Trials its principal focus, it provides the reader with a broader insight into the issues surrounding the Trials. Even in death, Samuel’s character has not rested from the Salem Witch Trials. In the epilogue LaPlante goes on to tell how Samuel’s great-grandson, Reverend Samuel Joseph May (1797-1871), a Unitarian minister, wrote in his memoirs about his great-grandfather. He wrote about Samuel Sewall, “He ‘was among the first to suspect, and afterward to expose, the delusion’ of the witch hunt, and he ‘strove in so many ways to atone for that early wrong’” (272-273). Nearly a hundred years later the historian Charles Upham wanted to ‘leave before your imagination one [scene] bright with all the beauty of Christian virtue.’ That was ‘Judge Sewall standing forth in the house of his God and in the presence of his fellow-worshippers, making a public declaration of his sorrow and regret of the mistaken judgment he had cooperated with others in pronouncing. Here you have a representation of a truly great and magnanimous spirit,’ which had achieved a ‘victory over itself; a spirit so noble and pure, that it felt no shame in acknowledging an error, and publicly imploring, for a great wrong done to his fellow-creatures, the forgiveness of God and man’ (273-274). Over three hundred years later authors such as Eve LaPlante continue to write about Sewall’s remarkable repentance because, as she notes, “Samuel Sewall’s world is less distant than it seems. We too may never transcend superstition and misjudgment. Yet he can be our guide in acknowledging and rectifying our wrongs. Like him, we are capable of a change of heart” (274).