Services for Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual

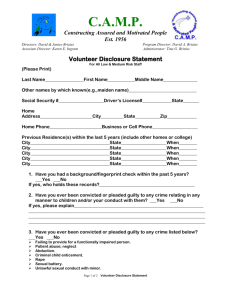

advertisement