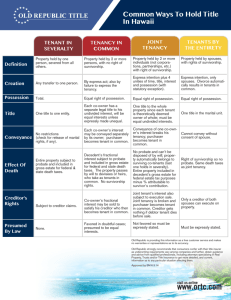

Property

advertisement