Note Taking - danesorensen

advertisement

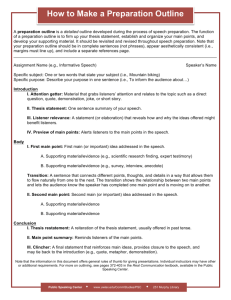

Note Taking In every class that I have taught over 98% of all students tell me that they want to go on to college. The cold reality of post secondary education is that many colleges are very competitive and offer little help in teaching the study skills necessary to survive. Many bright students fail within the first semester and drop out of college because they do not have the skill of note taking. Students do not realize that learning in college is their responsibility. Often the only assessments that will determine a semester grade are the midterm test, the final test and a research paper. A professor may only lecture on an important concept once. If that fact is covered in the first week of class, most students will have long forgotten it by the time the final exam rolls around twelve weeks later. I know I would have a hard time remembering twelve weeks later. It is only by taking notes that students can remember what was taught during class. Studies have shown that the average person forgets 95% of what they were taught by lecture within 24 hours. That is why notes are so important and the skill of note taking is a skill I concentrate on in class. Many of the South Carolina’s objectives from the state’s ELA Standards imply the need for note taking. Foremost is the objective, “Organize written works using prewriting techniques, discussions, graphic organizers, models, and outlines.” I feel the skill of note taking is so important that I review all student notes periodically and grade them on their efforts. I urge parents and students alike to review the following tips on note taking. I have found that students who take notes achieve an average of ten points higher on tests. That often results in going up one whole grade. In high school grades start to count toward a student’s GPA (Grade Point Average). A student’s GPA is one of the most important determining factors in deciding who enters college and who does not. During the first week of school I tell students that teachers are usually very transparent in what they want their students to learn. I am no exception. If I talk about a concept, if I write it on the board, if I project it on a screen, there is a very high chance it will show up in a test. College professors work in the same manner. Sincerely, Mr. Sorensen Evalute Your Present Note-Taking System Ask yourself: 1. Did I use complete sentences? They are generally a waste of time. 2. Did I use any form at all? Are my notes clear or confusing? 3. Did I capture main points and all subpoints? 4. Did I streamline using abbreviations and shortcuts? Here are some great pointers to help you take good notes! Five Important Reasons to Take Notes 1. 2. 3. 4. It helps you to remember information you would normally forget. It helps you to concentrate in class. It helps you prepare for tests. Your notes are often a source of valuable clues for what information the instructor thinks most important (i.e., what will show up on the next test). 5. Your notes often contain information that cannot be found elsewhere (i.e., in your textbook). Guidelines for Note-Taking 1. Concentrate on the lecture or on the reading material. 2. Take notes consistently. 3. Take notes selectively. Do NOT try to write down every word. Remember that the average teacher speaks approximately 125-140 words per minute, and the average notetaker writes at a rate of about 25 words per minute. 4. Translate ideas into your own words. 5. Organize notes into some sort of logical form. 6. Be brief. Write down only the major points and important information. 7. Write clearly. Notes are useless if you cannot read them later! 8. Don't be concerned with spelling and grammar. (but try to fix them later) Tips for Finding Major Points in Lectures The speaker is usually making an important point if he or she: 1. 2. 3. 4. Pauses before or after an idea. Uses repetition to emphasize a point. Projects an idea on a screen or gives you a handout with the information. Writes an idea on the board. Forms of Note-Taking 1. Outlining I. Topic sentence or main idea A. Major points providing information about topic 1. Subpoint that describes the major point a. Supporting detail for the subpoint 2. Patterning: flowcharts, diagrams 3. Listing, margin notes, highlighting 4. Definitions Ways to Reduce and Streamline Notes 1. Eliminate small connecting words such as: is, are, was, were, a, an, the, would, this, of. Eliminate pronouns such as: they, these, his, that, them. However, be careful NOT to elimate these three words: and, in, on. 2. Use symbols to abbreviate, such as: +, & for and, plus = for equals - for minus # for number x for times > for greater than, more, larger < for less than, smaller, fewer than w/ for with w/o for without w/in for within ----> for leads to, produces, results in <---- for comes from / for per For example: "The diameter of the Earth is four times greater than the diameter of the Moon." Becomes: "Earth = 4x > diameter of Moon." 3. Substitute numerals with symbols, for instance: Substitute "one" with 1 Substitute "third" with 3rd 4. Abbreviate: Drop the last several letters of a word. For example, substitute "appropriate" with "approp." Drop some of the internal vowels of a word. For example, substitute "large" with "lrg." Adapted from : http://www.arc.sbc.edu/notes.html The Academic Resource Center WHAT CAN BE DONE ABOUT LISTENING Ralph G. Nichols (Edited by Mr. Sorensen) The Supervisor's Notebook, Scott, Foresman & Co. Vol. 22, No. 1, Spring 1960 The business of becoming a good listener primarily consists of getting rid of bad listening habits and replacing them with their counterpart skills. TEN BAD LISTENING HABITS 1. Calling the Subject Dull Bad listeners often finds a subject too dry and dusty to command their attention and they use this as an excuse to wander off on a mental tangent. Good listeners may have heard a dozen talks on the same subject before, but they quickly decide to see if the speaker has anything that can be of use to them. The key to good listening is that little three-letter word use. Good listeners are sifters, screeners, and winnowers of the wheat from the chaff. G.K. Chesterton said many years ago that in all the world there is no such thing as an uninteresting subject, only uninterested people. 2. Criticizing the Speaker It's the indoor sport of most bad listeners to find fault with the way a speaker looks, acts, and talks. Good listeners may make a few of the same criticisms but they quickly begin to pay attention to what is said, not how it is said. They know that the message is ten times as important as the clothing in which it comes garbed. 3. Getting Overstimulated Listening efficiency drops to zero when the listeners react so strongly to one part of the presentation that they miss what follows. Withhold evaluation until comprehension is complete -- hear the speaker out. It is important that we understand the speaker's point of view fully before we accept or reject it. 4. Listening Only For Facts I used to think it was important to listen for facts. But I've found that almost without exception it is the poor listeners who say they listen for facts. They do get facts, but they garble a shocking number and completely lose most of them. Good listeners listen for the main ideas in a speech or lecture and use them as connecting threads to give sense and system to the whole. 5. Trying To Outline Everything Probably not more than a half or perhaps a third of all speeches given are built around a carefully prepared outline. Good listeners are flexible. They adapt their note taking to the organizational pattern of the speaker-they may make an outline, they may write a summary, they may list facts and principles -- but whatever they do they are not rigid about it. 6. Faking Attention The pose of chin propped on hand with gaze fixed on speaker does not guarantee good listening. Having adopted this pose, having shown the overt courtesy of appearing to listen to the speaker, the bad listener feels conscience free to take off on any of a thousand tangents. Good listening is not relaxed and passive at all. 7. Tolerating Distraction Poor listeners are easily distracted and may even create disturbances that interfere with their own listening efficiency and that of others. They squirm, talk with their neighbors, or shuffle papers. 8. Choosing Only What's Easy Often we find the poor listeners have shunned listening to serious presentations on radio or television. There is plenty of easy listening available, and this has been their choice. The habit of avoiding even moderately difficult expository presentations overflows into the classroom and results in poor listening skills. 9. Letting Emotion-Laden Words Get In The Way It is a fact that some words carry such an emotional load that they cause some listeners to tune a speaker right out: such as, affirmative action and feminist - they are fighting words to some people. 10. Wasting the Differential Between Speech and Thought Speed Americans speak at an average rate of 125 words per minute in ordinary conversation. A speaker before an audience slows down to about 100 words per minute. How fast do listeners listen? If all their thoughts were measurable in words per minute, the answer would seem to be that an audience of any size will average 400 to 500 words per minute as they listen. Here is a problem. It lures the listener into a false sense of security and breeds mental tangents. However, with training in listening, the difference between thought speed and speech speed can be made a source of tremendous power. Listeners can hear everything the speaker says and not what s/he omits saying; they can listen between the lines and do some evaluating as the speech progresses. Good listeners: Anticipating the next point. Good listeners try to anticipate the points a speaker will make in developing a subject. If they guess right, the speaker's words reinforce their guesses. Identifying supporting material. Good listeners try to identify a speaker's supporting material. After all, a person can't go on making points without giving listeners some of the evidence on which the conclusions are based, and the bricks and mortar that have been used to build up the argument should be examined for soundness. Recapitulating. With the tremendous thought speed that everyone has, it is easy to summarize in about five seconds the highlights covered by a speaker in about five minutes. Half a dozen summaries of the highlights of a fifty-minute talk will easily double the understanding and retention important points in a talk. Source: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~acskills/success/notes.html For more tips on being a better listener in class please read: Listening Skills