Mickey Mouse - Arizona State University

advertisement

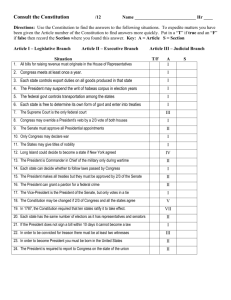

Roger P. Foley Art and Entertainment Law Professor Krieger 27 November 2002 Eldred v. Ashcroft and why the U.S. Supreme Court Should Reject the Entertainment Industry’s Thinly Veiled Attempt to Circumvent the Limitations of the U.S. Constitution’s Limits on Copyright Protection Laws Among the most important issues facing the entertainment industry today is the scope and level of protections available to the industry for its works. Chief amongst those protections are the federal copyright laws. These laws are now under considerable scrutiny as the United States Supreme Court decides whether or not to strike down as unconstitutional a major extension of the terms of protection provided for in those laws.1 As will be discussed, it is by no means accepted truth that the extension of the term of protections of the copyright laws is beneficial for the entertainment industry or even for society as a whole. Indeed, many argue that the chief proponent of the extension, Walt Disney Company (“Disney”), is being incredibly hypocritical.2 According to the critics, Disney has consistently exploited literary and other works whose copyrights have lapsed, and now, having improved or redone the works into a newly copyrighted film or other work seeks to extend copyright protection so that others cannot do that which it has already done.3 As a result, Mickey Mouse has become the lightning rod for a major battle between owners of copyrights and those who believe the laws are too protective of copyright owners. The first Mickey Mouse cartoon,“Steamboat Willie” was copyrighted 1 Eldred v. Ashcroft, Case No 01-618 (Oct. 11, 2001). John Bloom, Right and Wrong: The Copy-Right Infringement (2002) at http://www.nationalreview.com. 3 Id. 2 1 in 1928, and as such was scheduled to enter the public domain in 2003, potentially leaving Mickey Mouse’s master, Disney, unprotected.4 Characters such as Donald Duck and Goofy would have followed shortly thereafter.5 Rather than allowing Mickey and friends to enter the public domain, which would cost Disney billions of dollars, Disney and its friends in the entertainment industry, undertook a massive campaign to convince Congress to pass a copyright extension bill.6 In support of their request Disney and the industry donated more than $7.8 million dollars to all congressional candidates’ 19971998 campaign coffers.7 This big dollar financial lobbying convinced Congress to pass the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act in 1998 (“CTEA”).8 The CTEA9 adds 20 years to the renewal terms of pre-1978 copyrights (making them effective for a period of 95 years from first publication).10 It also adds 20 years to the term for works created after 1977, which copyrights do not have to be renewed and, also sets the term of copyright at life plus seventy years for individual authors and at 95 years from publication for corporate authors.11 This effectively prevents works that were due to enter the public domain in the near future from being utilized by the general public for another twenty years. The CTEA, however, has attracted substantial critics predominantly from intellectual circles. Critics of the CTEA argue that it should be struck down as 4 Chris Sprigman, The Mouse that Ate the Public Domain: Disney, The Copyright Term Extension Act, and Eldred v.Ashcroft,” (2002) at http://www.writ.news.findlaw.com 5 Id. 6 Id. 7 Id. citing The Non-Profit Center for Responsive Politics at http://www.opensecrets.org/industries/summary.asp?Ind=B02&cycle=1998&recipdetail=A&sortorder=U. 8 Id. 9 Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act in 1998, Pub.L. No. 105-298, Title I, Section, 101, 112 Stat. 2827. 10 Id. 11 Id. 2 unconstitutional both on First Amendment grounds and on the basis that it was outside Congress’s power under the U.S. Constitution’s “promotion of progress of science” clause quoted below. Foremost among these critics is Eric Eldred, a hobbyist, who publishes rare books online for others who may not otherwise be able to view such lost works.12 Eldred argues that the CTEA is “unconstitutional because it prevents works from entering the public domain, diminishing access to information in violation of the First Amendment,13 but did not increase authors’ incentives to create.”14 The intellectual community has rallied around Eldred. Indeed, now that Eldred’s case has reached the U.S. Supreme Court scores of groups have filed amicus curiae briefs supporting his position.15 The defense of the CTEA has fallen to the U.S. Department of Justice.16 The government in its defense of the CTEA argues that the provisions of the CTEA, including the extension provisions, are consistent with the copyright clause of the United States Constitution which grants Congress the power: To promote the progress of science and the useful arts by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.17 The government asserts that CTEA meets the “promotes requirement” requirement in several ways by: 1) harmonizing copyright law with the law of the Joyce Slaton, “A Mickey Mouse Copyright Law,” Wired, January 13, 1998; see also Brief of Petitioners, Eldred v. Ashcroft, Morris Tyler Moot Court of Appeal at Yale, at 1, available at http//eon.law.harvard.edu/openlaw/eldredvashcroft/reference/yale-mootcourt.html. 13 The First Amendment issues are beyond the scope of this paper, instead, this paper will focus on the arguments relating to the “promotion of progress of science” clause. 14 Brief of Petitioners, Eldred v. Ashcroft, Morris Tyler Moot Court of Appeal at Yale, at 4, available at http//eon.law.harvard.edu/openlaw/eldredvashcroft/reference/yale-mootcourt.html. 15 See Docket Eldred v. Ashcroft, U.S. Supreme Court, Case No, 01-618 (Oct. 11, 2001) 16 Id. 17 Brief of Respondents, Eldred v. Ashcroft, Case No, 01-618 at 9, 39 (Oct. 11, 2001), citing U.S. Const. art. I, §8, cl. 8. 12 3 European Union; 2) encouraging the preservation of at-risk materials; and 3) providing more financial resources for potential authors.18 Of these, the principal argument in favor of upholding the CTEA is that it is essential to harmonize the U.S. copyright laws with those of the European Union.19 The case was argued on October 9, 2002 and a decision is expected in summer 2003.20 As will be discussed in this paper, the government’s arguments while facially supportive of the CTEA, once examined, are actually inconsistent with the Framer’s intent in adding the “promotes requirement” to Art. I, §8, cl. 8, of the U.S. Constitution. KEEPING UP WITH THE JONES FAMILY IS UNPERSUASIVE ARGUMENT IN SUPPORT OF THE CTEA AN The proponents of CTEA argue that it would be wise to extend copyright protection in the United States to a term of the life of the author plus seventy years, because it would match the term recently adopted in Europe under the European Council Directive (“EC Directive”). British novelist Julian Barnes, however, disagrees in his recent article where he states that the European Union’s version of the law has produced nothing but ambiguity, absurdity, and litigation since being modified itself.” 21 At the very least, he wrote, “the situation will be foggy until the full cycle of appeals has been exhausted.”22 The government’s view of harmonization with the European Union is analogous to the proverbial neighbors’ attempt to keep up with the Jones Family. However, similar to the proverbial Jones’ neighbor, just because the E.U. extended copyright protection to a term of seventy years after the death of the author does not mean that the United States’ 18 Id. at 9-23. Id. 20 See Docket Eldred v. Ashcroft, U.S. Supreme Court, Case No, 01-618 (Oct. 11, 2001) 21 Julian Barnes, Copyright Wrongs, Wall Street Journal (January 31, 2001) 22 Id. 19 4 decision to follow suit is correct. The original goal of copyright protection was to foster the continual progress and innovation of a man and his works. Such goal is expressly included in the United States Constitution, Article 1, Section 8 which vests Congress with the right, “to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” In adding this clause to the Constitution, our forefathers sought to further innovation by offering an adequate level of protection to guard against infringement, but not so much individual protection as to stall progress and hinder future innovation. The concept was simple: protect the creator’s innovation long enough that he can make a profit from his creation but not so long as to prohibit others from furthering or improving on that creation – thereby creating a necessary balance of protection and furtherance of creativity.23 Congress, in passing the CTEA forgets that protection of an individual’s work, or in this case a multi-million dollar corporation’s copyright, is not paramount to innovation. The two must be balanced. This balance allows the author’s works to be protected for a sufficient time and then enter the public domain where it can be used, manipulated, and improved in a manner which fosters the innovative and creative spirit of man. By tilting this balance of protection, Congress in passing the CTEA now has copyright owners more concerned about protecting the financial benefits to be derived from their inventions, than about improving them so that all of society may benefit. 23 This balance was a key principal underlying the addition of the copyright clause to the Constitution, as expressed in correspondence between Jefferson and Madison. In their correspondence, they expressed: “Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property. Society may give an exclusive right to the profits arising from them, as an encouragement to men to pursue ideas which may produce utility, but this may or may not be done, according to the will and convenience of the society, without claim or complaint from anybody.” See http://digital.library.upenn.edu/books/bplist/archive/1999-02-11$2.html 5 An example of such a tilted balance can be seen by examining a current patent dispute.24 In that case, the drug company, AstraZeneca, which makes Losec -- the phenomenal “purple pill” that, for the last five years, has been the world's biggest-selling prescription drug -- holds a U.S. patent on that drug which was due to expire in April of 2001.25 The company secured a six-month patent extension based on its assertion that Losec has a “new “additional use for pediatric disorders. AstraZeneca’s critics contend that the company is making immaterial changes to the drug, which offer no new benefit to users or society as a whole, and is strategically varying the molecular structure for the sole purpose of artificially extending the patent rights which afford the company more than $4 billion dollars a year in sales.26 At the same time, these extensions prevent others from improving on the drug or from providing the drug at a lower cost to consumers.27 Elliot Hahn, president of the Florida pharmaceuticals firm Andrx, says: "They've taken a single patentable idea, extended it and extended it well beyond its life cycle, using deft manipulation of the litigation process."28 He accuses Britain's second largest drug firm of filing "extremely weak and, in some cases, manifestly bogus" intellectual property claims first to keep the legal process going beyond the allowable period.29 Such harboring and extended protection of this invention dwarfs new and innovative ideas and improvements.30 The net result is research laboratories with more lawyers than Andrew Clark, AstraZeneca’s Purple Pill Show, http://www.guardian.co.uk.business/story/0,3604,533166,00.html 25 Id. 26 Id 27 Id. 28 Id. 29 Id. 30 Id. 24 6 (August 7, 2001) at researchers, which increases costs to the consumer and less innovation.31 The CTEA threatens a similar result in the area of copyright protections. A fundamental flaw in the government’s harmonization argument is that keeping pace with the E.U. does not signify harmonization with the rest of the world. The United States is not a member of the European Union but it is a member of the Berne Convention. The Berne Convention requires the life plus 50 rule and most of its members believe that rule to be satisfactory, as evidenced by their strict adherence to Berne.32 In fact, on October, 11, 2002, just two days after the United States government argued harmonization as a global standard, Taiwan rejected U.S. demands to increase its copyright terms by 20 years.33 There are 149 countries that adhere to the rules and regulations of Berne.34 More than two-thirds of those countries subscribe to the “life plus 50 rule” as opposed to the minority one-third which adheres to the “life plus 70 rule” which the government contends the U.S. needs to harmonize with.35 Indeed it may be argued that the U.S., through adoption of the CTEA, has actually digressed from the majority of harmonized countries to the minority. 36 It may be further argued that the United States has a better opportunity for achieving world harmonization by adhering to “life plus 50 rule” than the rules proscribed by the CTEA. More importantly, however, even accepting the need to harmonize with the E.U., the government’s argument regarding harmonization is somewhat deceptive. Marybeth Peters, Register of Copyrights, testified before the U.S. Congress that the bill “does not 31 Id. See J.H. Reichman, The Duration of Copyright and the Limits of Cultural Policy, 14 Cardozo Arts & Ent. L. J. 625, 628-31 (1996). 33 Lawrence Lessig, Time to End the Copyright Race, (October 16, 2002) at http://www.financialtimes.com. 34 See National Copyright Legislation, available at http://www.unesco.org/culture/copy 35 Id. 36 Brief for petitioners, Eldred v. Ashcroft, Case No 01-618 (Oct. 11, 2001). 32 7 completely harmonize our law with the [E.U. Directive].”37 For example, there are instances where, under the CTEA, the U.S. copyright term will exceed that of the E.U.’s protection and vice-a-versa – a result which scholars contend actually increases the disharmony between the U.S. and E.U..38 As additional evidence that “harmony” will, in practice, be virtually impossible to achieve, it now appears that many Europeans are pushing for yet another extension of copyright terms.39 In fact, to see the flaw in the government’s harmonization argument, one need only look at the European Union’s treatment of the problem, which attempts to harmonize E.U. Rules with those of countries offering less protection by implementing the “rule of the shorter term.”40 This “rule of shorter term” allows the majority of the countries to receive the same protection which that country gives to the E.U.’s works. For example, if Canada adhered to the life-plus-50 rule, then members of the European Union would only protect Canadian copyrighted works for terms of life-plus-50 as well. Proponents argue that this will result in “ …20 years during which Europeans will not be paying Americans for their copyrighted works, while a similar European work would be protected.”41 That is analogous to the glass is half-empty analysis. However, Joseph A. Lavagine, replies the glass is half full when he states, “these individuals 37 Copyright Term, Film Labeling, and Film Preservation Legislation: Hearings on H.R. 989, H.R. 1248, and H.R. 1734 Before the Subcomm. on Courts and Intell. Prop. of the House Comm. on the Judiciary, 104th Cong., 420 (1995) 38 See Dennis S. Karjala, Chart Showing Changes Made And The Degree Of Harmonization Achieved And Disharmonization Exacerbated By The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA) Created May 15, 2002. 39 Lawrence Lessig , Time to End the Copyright Race, (October 16, 2002) at http://www.financialtimes.com 40 European Union Directive 93/98/EEC on Copyright Term of Protection Article 7 (Protection vis-à-vis third countries where the country of origin of a work, within the meaning of the Berne Convention, is a third country, and the author of the work is not a Community national, the term of protection granted by the Member States shall expire on the date of expiry of the protection granted in the country of origin of the work, but may not exceed the term laid down in Article 1). 41 141 Cong. Rec E379 (daily Ed. Feb. 16, 1995) (statement of Representative Carlos Moorehead of California). 8 [proponents] fail to realize that during those same twenty years, Americans will not be paying Europeans for their copyrighted works either.” 42 The intellectual dishonesty of the proponents’ arguments is perhaps best demonstrated by the fact that proponents profess to be concerned about Americans losing money if copyright terms are not extended, yet, however, the CTEA actually costs American creators even more money because it fails to contain a “rule of shorter term.” The CTEA’s failure to have a “rule of shorter term” increases copyright protection for all works in the United States, regardless of origin, therefore extending the cost to Americans who seek to use a foreign creators’ expired copyright. Thus, under the CTEA, which has “no rule of shorter term,” an adhering Berne member who allows its authors a protection of life plus 50 years will receive 20 years additional protection in the U.S., although in his origin country copyright protection has already ended. This means members of that Berne country need not pay for the use of that work but Americans wishing to use the same work at the same time, would be required to pay compensation to the copyright owner. The CTEA is even less harmonized with respect to certain authors, certain kinds of work, and some works in particular. CTEA increases disharmony, for example, with respect to “corporate authors.” The E.U. offers “corporate authors” in countries like the United States where that concept is recognized a term of protection for 70 years, whereas the CTEA expands the term of protection for “corporate authors” to 95 years or 120 years if the work is unpublished.43 This is particularly troubling because, historically, the goal of copyright 42 Joseph A. Lavagine, For Limited Times? Making Rich Kids Richer Via the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1996, 73 U.Det. Mercy L.Rev. No.2 Winter 1996. 43 See Jane C. Ginsburg, Copyright Legislation for the “Digital Millennium, 23 Colum.-VLA J.L. & Arts 137, 172 (1999). 9 protections in the U.S. has not been to create wealth, but rather to stimulate innovation. The European Union has always had a far different intellectual property theory. The E.U. proscribes to a natural rights theory that treats copyright protection as a simple entitlement. 44 Accordingly, the E.U. theory on copyright is to enrich creators of work rather than to enrich society. In the United States, however, copyright protection has always been based on the U.S. Constitution’s directive in Article 1, Section 8 which vests with Congress the right “To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries”. (Emphasis added). Promoting the progress of large corporations and creating monopolies for copyright owners was not the intent of the forefathers. “The monopoly privileges that Congress may authorize are neither unlimited nor primarily designed to provide a special private benefit. Rather, the limited grant is a means by which an important public purpose may be achieved. It is intended to motivate the creative activity of authors and inventors by the provision of a special reward, and to allow the public access to the products of their genius after the limited period of exclusive control has expired.” 45 Thus, as expressed by the Supreme Court, the U.S.’s constitutional directive on limited economic incentives rejects any notion of natural rights.46 Yet, by enacting the CTEA and extending the term of copyright protections to 44 See Sam Ricketson, The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works: 1886-1986 5-6 (1987) “([Eighteenth century French copyright laws placed authors’ rights on a more elevated basis than the [British] Statute of Anne. . . . [T]he rights being protected [were treated] as being embodied in natural law. . . . This new conception of author’s rights had a great effect on the law of France’s neighbors. . . .”). 45 Sony Corp. of Am. v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417, 429 (1984). 46 See 33 U.S. (8 Pet.) at 657-63, see also H.R. Rep. No. 2222, at 7 (1909): The enactment of copyright legislation by Congress under the terms of the Constitution is not based on any natural right that the author has in his writings, for the Supreme Court has held that such rights as he has are purely statutory rights, but on the grounds that the welfare of the public will be served and the progress of science and useful arts will be promoted. . . . By the same token, in the United States copyright is viewed as an “impingement on the 10 serve the whims of entertainment giants such as Disney, Congress is doing nothing more than creating de facto natural rights in copyright owners. Consequently, the argument for harmonization with the European Union cannot support the argument for upholding the CTEA if we are to adhere to the clear language of our own constitution. The purpose of the U.S. Constitution, in Article 1, Section 8 is “to promote the progress of science and useful arts” to the public, not to benefit any private enterprise. Indeed, as explained by the U.S. Supreme Court “the sole interest of the United States and the primary objective in conferring the [limited] monopoly …lie in the general benefits derived by the public from the labors of authors. 47 Thus, the suggestion that Congress properly exercised its power in passing the CTEA in order to harmonize U.S. law with the E.U. Directive, is not only contrary to the above-mentioned constitutional authorities, but is also contrary to the best interest of society as a whole. THE GOVERNMENT’S ARGUMENT THAT THE CTEA ENCOURAGES THE PRESERVATION OF AT-RISK MATERIALS IS WITHOUT MERIT The government’s alternate argument that term extensions promote the preservation of works, especially historical films, is similarly without support. An amicus brief filed by the College Art Association48 demonstrated that no credible evidence was presented to Congress or the lower courts that would indicate assertions made by the government had any validity.49 In contrast to the government’s position, the public domain,” a concept that would have no meaning in the European philosophical context. See L. Ray Patterson, Free Speech, Copyright and Fair Use, 40 Vand. L. Rev. 1,7 (1987). 47 Twentieth Century Music Corp. v. Aiken, 422 U.S. 151, 156 (1975), quoting Fox Film Corp. v. Doyal, 286 U.S. 123, 127 (1932); see also Nimmer on Copyright §1.03[A] (2001) (stating that the “primary purpose of copyright is not to reward the author, but . . . to secure the general benefits derived by the public from the labors of authors.” 48 See Brief or Amicus Curiae, College Art Ass’n., at 19-20 (premised on Copyright Term, Film Labeling, and Film Preservation Legislation: Hearings on H.R. 989, H.R. 1248, and H.R. 1734 Before the Subcomm. on Courts and Intellectual Property of the House Comm. on the Judiciary, 104 th Cong. (1995)). 49 Id. 11 College Art Association’s brief argues that “extended terms reduce the likelihood that the films will be restored.”50 For a film to be restored, a determination must be made if it is copyrighted, and then the person or company holding the rights to it must be located. However, this becomes very difficult for older works or for copyright holders who have simply disappeared. If the copyright owner cannot be found, then the public must wait until that work enters the public domain, which means another 20 years for many works. This increased period of time makes preservation impossible for independent enthusiasts and entrepreneurs due to decomposition.51 In contrast, the government’s argument assumes that the work is always in the possession of the person or entity accorded the copyright, which is often simply not the case.52 Even if, a person or entity has acquired both the copyright and the tangible work, it is unlikely that they are stored in a manner conducive to their preservation.53 Studies have shown that those in possession of the actual work often cause their destruction by improper handling or careless disregard.54 All of these factors would indicate a need for works, such as deteriorating films, to be placed in the public domain sooner rather than 50 Id. See John McDough, Motion Picture Films and Copyright Extension (2002), at Http://public.asu.edu/~dkarjala/commentary/McDonough.html (cited in Brief of Amici Curiae National Writers Union No. 01-618 at 22. 52 See e.g. 17 U.S.C. §202 (ownership of copyright is distinct from ownership of any material object in which a work is embodied). 53 See Brief or Amicus Curiae, American Ass’n . of Law Libraries., at 26 (citing National Film Preservation Board, Film Preservation 1993: A Study of the Current State of American Film Preservation: Report of the Librarian of Congress § 2 (1993) (“1993 Film Study”). 54 See National Film Preservation Board, Film Preservation 1993: A Study of the Current State of American Film Preservation: Report of the Librarian of Congress § 2 (1993) (“1993 Film Study”) (“a great percentage of American film has already been irretrievably lost — intentionally thrown away or allowed to deteriorate”; “fewer than 20% of the features of the 1920s survive in complete form”; preservation problems most acute for works of little commercial value, like newsreels, documentaries, avant-garde and independent productions); see also 1 National Film Preservation Board, Television and Video Preservation 1997: A Report on the Current State of American Television and Video Preservation: Report of the Librarian of Congress, Executive Summary (1997) (kinescope or film copies of early live television broadcasts were made selectively, other programs deliberately destroyed, videotapes erased and recycled; most devastating losses are of local television station news footage). 51 12 later, where they can be transferred to a longer lasting medium, not left to decay for another 20 years.55 The government’s preservation argument also incorrectly equates the idea of preservation to progress in an attempt to fit within the language of the Constitution’s copyrights clause. The two terms, however, are distinctly different by definition. “Preservation” is synonymous with maintenance, conservation, and safeguarding, while “Progress” relates to growth, development, and forward movement.56 The government argued to the appellate court that an existing copyright may not actively stimulate creative development, but that the CTEA does induce would-be extended copyright holders to preserve existing works, such as old films.57 But as previously discussed, “preservation” does not equal “promotion” and therefore, this argument fails to establish that the retroactive extension of copyrights accomplishes the “promotion” directive set forth in the copyright clause of the Constitution. PROVIDING MORE FINANCIAL RESOURCES FOR POTENTIAL AUTHORS THROUGH RETROSPECTIVE TERM EXTENSION IS THE GOVERNMENT’S WEAKEST ARGUMENT The fact that the CTEA will provide current copyright holders extended term protection is irrelevant when you consider that many of the original creators have been deceased for many years. Any resulting payments will either go to their families or to entertainment companies. From a common sense standpoint it is doubtful that a family member two generations removed from the creator will use any proceeds derived from 55 Id. Webster’s new World Dictionary and Thesaurus, Second Edition, May 2002. 57 Brief of Respondents, Eldred v. Ashcroft, Case No, 01-618 at 9, 39 (Oct. 11, 2001). 56 13 the CTEA to create new works.58 However, it may be argued that entertainment companies will refinance profits from existing works into new enterprises. However, this amounts to a corporate subsidy rather than an incentive to create.59 More importantly, however, future authors will have added disincentives to create new “improvements” due to the CTEA. Works that would have been in the public domain, and therefore free to be used by anyone, will need to be cleared by the owners of the copyright. That means not only unnecessary financial cost for using the rights, but also creates stumbling blocks on how the work may be used from a creative standpoint. Owners of the copyright may not agree with the new artists’ perspective and could impose limits on its use. These factors hinder the creative process. CTEA VIOLATES THE “LIMITED TIMES” REQUIREMENT OF THE COPRIGHT CLAUSE The lower court in Eldred has upheld that CTEA's extension of limited times is within the discretion of Congress. 60 And Congress has used that discretion eleven times in the past forty years.61 This virtually perpetual extension of terms amounts to an unconstitutional misuse of Congress’s power in direct conflict with Article !, Section 8, of the Constitution’s clear directive that the terms of a copyright shall be limited. The constitution was written in a manner that dictated that copyright protection be “limited” 58 See United Christian Scientists v. Christian Sci. Bd. of Dirs., 829 F. 2d 1152, 1168 n. 84 (D.C. Cir. 1987) (“[A] grant of copyright protection after the author’s death to an entity not itself responsible for creating the work provides scant incentive for future creative endeavors.”). 59 See, e.g., 1995 Senate Hearings, supra note at 55-57 (statements of Don Henley, Bob Dylan and Carlos Santana) ( asserting that support of the CTEA was based primarily on the potential exploitations of their grandchildren); compare with S. Rep. No. 104-315, at 32 (1996) (statement of Sen. Brown in dissent): There is nothing in the hearing record that suggests extending the copyright term will result in more works or higher quality works. Indeed our success as a nation of creators suggests the opposite: another 20 years of revenue from current works might, for example, subsidize new motion pictures. However, this is more a corporate subsidy than an incentive to create. 60 Eldred v. Reno, 74 F. Supp. 2d 1, 3 n. 6 (D.D. C. 1999) (citing Schnapper v. Foley, 667 F. 2d 102, 112 (D.C. Cir. 1981), cert. denied, 455 U.S. 948 (1982). 61 Eldred v. Reno, 239 F. 3d at 381. 14 so as to prevent unfair monopolies.62 “Limited times” appears in the copyright clause to confer a temporary right upon man so that he may protect his created work for a reasonable time enabling him to recoup his expenses and make a reasonable profit. 63 The obvious effect of the financial incentive was to motivate a creator so that he would continue to create and that as a result all of society would benefit from those creations both before and after they entered the public domain.64 It was intended that upon expiration of these “limited times” of protection that works would enter the public domain where they could be used fully and liberally by all society. 65 Such limited times was intended to encourage potential creators to tinker, twist, and adjust works that had entered the public domain in a manner that ultimately altered the then existing creation into a more advanced one. This has been the logic since the adoption of the U.S. Constitution and our society has flourished as a result. Now the CTEA threatens the public domain- the place society has historically gone to as a fertile ground to accelerate creative advances. Thus, the CTEA may seriously disrupt creative progress; however, the real danger is that we may not fully realize the extent of this disruption for several years – when the damage may already be too advanced. CONCLUSION As set forth in the discussion above, Congress’s enactment of CTEA and the government’s defense of same is nothing more than a thinly disguised attempt to circumvent the Framer’s explicit intent to limit the term of copyright protection in favor of the societal goal of promoting and fostering progress and innovation. By claiming that 62 Sony Corp. of Am. v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417, 429 (1984). Joseph A. Lavagine, For Limited Times? Making Rich Kids Richer Via the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1996, 73 U.Det. Mercy L.Rev. No.2 Winter 1996. 64 Id. 65 Id. 63 15 extensions for a set limited term are still “a limited time,” Congress and proponents of the CTEA have created tremendous uncertainty, because what they call limited today may change at a moment’s notice. The result is that no artist can rely on a work ever entering the public domain again. That means no tinkering, twisting, or adjusting for what amounts to an indefinite time because every day one must wonder when will Congress change it again, which obviously hinders creation and threatens to create a “monopoly of the work already in existence.”66 Such a result, threatens the very core of this country’s legacy of progress and innovation. To argue that this extension is necessary to harmonize U.S. law to the view in a minority of jurisdiction merely highlights the fact that the CTEA is nothing more than an effort to appease a special interest group – the corporate giants of the entertainment industry. This is simply inconsistent with the explicit provisions and limitations of Article I, Section 8, Clause 8, of the U.S. Constitution. Therefore, for the foregoing reasons the Supreme Court should find that the CTEA violates the Copyright clause of the U.S. Constitution and strike it down as unconstitutional. 66 See Trade-Mark Cases, 100 U.S. 82, 94 (1879) (cited in Morris Tyler Court of Appeals At Yale- Spring Term 2002 No. 01-618 by Chrimene Keitner and Travis Leblanc). 16