Immunology 4

advertisement

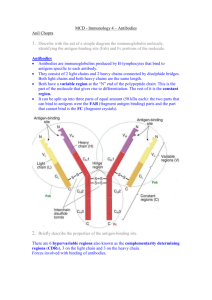

Immunology 4 - Antibodies Antigens are referred to as foreign or non-self molecules. However, it is important to make a distinction between antigens which bind to antibodies by using their particular epitopes and immunogens which are antigens which can always bring about an immune response on binding. The point is that antigens need not always bring about an immune response but immunogens always do. Some molecules may well bind to antibodies very strongly, etc but they are not capable of bringing about a proper response; an appropriate example would be pennicillin. Such molecules are often referred to as haptens. Effective immunogens to the host are generally large molecules with huge molecular weights present on an accesible part of the pathogen, the surface does the trick usually and they must be chemically diverse; obviously antigens made from twenty or so different proteins have a higher capability of bringing about an immune response as opposed to nucleic acids antigens made from only four possible subunits. The terms antigen, antigenic determinants and epitopes is often used loosely and interchangeably. Strictly speaking, however, an epitope refers to the particular area on a given antigen which the antibody can bind to. An epitope is the point where the antibody uses its antigen binding site and binds to the antigen. It is important to note that a given pathogen may contains antigens which have a number of different epitopes and it is only necessary for the body to produce antibodies capable of recognizing only one of those epitopes in order to bring about an effective immune response against the particular pathogen by interfering with its reproduction or killing it, etc. Two different kinds of epitopes exist, discontinuous epitopes occur due to amino acids or different points in a given antigen molecule being brought together from some distance away forming a particular 3D structure which is then bound to an antibody resulting in the antigen-antibody reaction. In contrast, we have linear epitopes which simply recognizes a given set of amino acids in a linear format. Due to the specific shape of products of MHC in humans, the T cells are only capable of recognizing linear epitopes. Discussed in later lectures. An antibody is a molecule which is produced by the body in response to a particular antigen and has the property of binding specfically to the particular antigen which induced its formation. All antibodies are known to have the same basic structure. They all consist of two heavy and two light chains. This is referred to as the very basic chemical unit which can be called an antibody. Of course, lgM is multivalent and incorporates FIVE of these units. Discussed at length later. The light chains have half the molecular weight of the heavy chains. They have a weight of about 25 kDa as opposed to the 50 kDa found in heavy chains. The two chains are linked together by intermolecular disulphide bridges. Five different classes of heavy chain exist in the five different classes of antibodies. If the five different classes are GAMDE, then the five different chains in order are, gamma, alpha, mu, delta, epsilon. Two different kinds of light chain exist, kappa or lambda. They can exist in all five classes but note that in any given antibody, only ONE can exist at any given moment. In other words, a particular antibody can have ONE class of heavy chain, which determines the class of the antibody itself, in fact, and ONE class of light chain. The basic immunoglobulin structure involves the polypeptide adopting a particular three-dimensional structures and forming particular domains. These domains are in fact, a common feature in a number of molecules involved in the immune system and members of the immunoglobulin supergene family. A number of biochemical studies have shown that the structure of antibodies involves different parts with different specific functions. When subjected to proteolytic cleavage by a number of enzymes, we have the elucidation of a structure which contains a Fab region or antigen-binding region and an Fc region, which is capable of crystallizing and which is responsible for a number of activities which define antibodies, once bound to antigens. Pepsin divides the antibody molecule into two segment, Fab squared and a digested Fc fragment. Papain, on the other hand, results in three total fragments, two capable of binding antigen and one capable of bringing out a number of other effector functions such as binding to particular Fc receptors on a number of cells, such as macrophages, to certain complement components, etc. Functions of the antibody-antigen complex include the aformentioned opsonization, complement activation and ADCC in NK cells. Amino acid sequencing studies have revealed that there are certain constant regions in the light and heavy chains which are not strictly constant but exhibit limited variation between individuals and variable regions which exhibit enormous variation within the particular individual. Within these variable regions are three hypervariable regions, thought to be directly responsible for binding the epitope, which are made of a number of complementarity determining regions. Note that both the H and L chains have variable and constant regions. The V regions bind antigen, due to their enormous diversity, etc, they can recognize many different antigens and the C regions are responsible for the effector functions. As mentioned before, the three-dimensional structure involves the folding of the antibody polypeptides into a number of clearly distinct functional domains. It has been found that L chains have one variable and one constant domain as opposed to the H chains which have one variable and three constant domains. Each domain is approximately 110 amino acids long, separated from the next, by a slightly less organized region of polypeptide and held by intramolecular disulphide bonds into loops of about 60 or so amino acids. Antibodies may also have a hinge region which allows a degree of flexibility in their binding to the antigens, allowing them to re-adjust their conformation and bind effectively to antigens which can be close together on the pathogenic surface or far apart. I must now, at this point, distinguish between antibody affinity and avidity. Note that antibodies bind to their antigens purely by means of various non-covalent interaction. These are, in fact, quite similar to the non-covalent interaction which are responsible for the tertiary structure of proteins. Hydrogen bonds are involved, ionic bonds, hydrophobic interactions all play a part. The strength of binding between a particular antibody and the epitope of its cognate antigen is referred to as the antibody affinity; it includes only the strength of one particular interaction. However, antibody avidity is a much better representation of the overall strength of binding between antibody and antigen because it takes into account the strength of the multiple interactions between an antigen and an antibody. Following the logic, multivalent antibodies with numerous binding sites will be far more effective in binding to antigens as opposed to a particular antibody which is monovalent. Antibody cross-reactivity is also an important concept. Due to the sheer variety of possible structures for antigens it is common to find that immunity from exposure to one particular antigen can often result in cross-reactive immunity to a structurally similar antigen which may come from a similar family. Vaccination with cowpox provides protection against smallpox. The ABO blood grouping system. Antibodies produced against the antigens of bacteria residing in the gut may well cross-react with the carbohydrate receptors present on erythrocyte surfaces. There are, as mentioned before, different classes of antibody in man. Immunoglobulin G Class Heavy chain Gamma class Subclasses G1 to g4 A M D E Alpha Mu Delta Epsilon A1 and a2 None None None Lg G is the most prevalent antibody in serum; it is the most common. It has the longest half-life, is able to cross the placenta to provide passive immunity to the newborn; four subclasses are present with slightly different functions owing to their different structures, variability between subclasses stems mostly from the hinge region. Has a number of functions, opsonization, activation of complement, antibody mediated cellular cytotoxicity, important for the functioning of NK cells. The Fc receptor for lgG is in fact, present on a number of cells, such as macrophages and when such cells bind to the antigen-antibody complex, it activates them. Lg A can be found as a monomer in blood or more important, as a dimer in a number of mucosal secretions coating the epithelia of the GI, genital and respiratory tracts. Composed of two molecules of lg A, a J component, and a secretory protein which is derived from the receptor, which aids the transport of the lg A molecules and J component from the blood to the epithelial secretion. Found in breast milk. Protects the epithelia from bacteria, viruses and protozoa. Lg M is the predominant antibody involved in the primary immune response. It has a multivalent structure with five H2L2 units, resulting in a total of ten antigen binding sites. It is the most efficient antibody at agglutination and activating complement. Lg d is not that well known unfortunately. It is thought to exist on the surfaces of all B cells and is involved in B cell proliferation, discussed at length in the following lecture. Lg E can bind to mast cells and basophils utilizing its Fc component. It causes their degranulation, causing the release of histamine and other inflammatory mediators. Initially developed to fight against various parasitic infection; however, it now often play a great role in allergies. Distribution of Lgs is such that G is found in blood, along with M. G is found in external secretions, can move across placenta, present in breast milk. Dimeric lg A is found in secretions coating epithelia, lg E is found with mast cells and basophils. The brain is devoid of immunoglobulins.