Anatomy of the Larynx The larynx consists of four basic anatomic

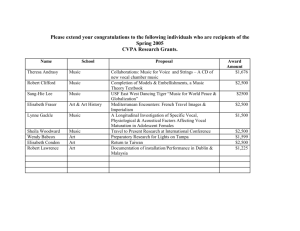

advertisement

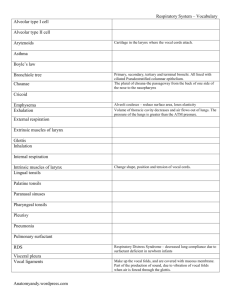

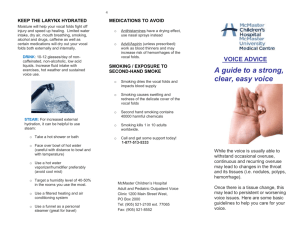

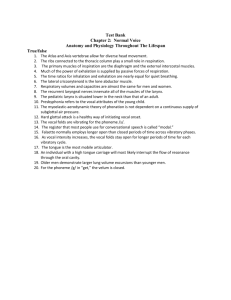

Anatomy of the Larynx The larynx consists of four basic anatomic components: a cartilaginous skeleton, intrinsic and extrinsic muscles, and a mucosal lining The cartilaginous skeleton, which houses the vocal cords, is comprised of the thyroid, cricoid, and arytenoid cartilages (Fig.1). These cartilages are connected to other structures of the head and neck through the extrinsic muscles. The intrinsic muscles of the larynx alter the position, shape and tension of the vocal folds (Fig. 2) Functions of the Larynx The larynx functions in deglutition (swallowing), respiration (breathing), and phonation (voice production). The production of voice can be thought of in terms of three components: the production of airflow, the generation and resonance of sound and the articulation of voice. (Fig.2) Production of Airflow The lungs first supply adequate airflow to overcome the resistance of the adducted vocal cords. The vocal cords are finely tuned neuromuscular units that adjust pitch and tone by altering their position and tension. Sound Production Sound production occurs due to the vibration of the mucosa at the inner edge of each vocal cord. Thus any structural, inflammatory, or neoplastic lesion of the vocal cord affects voice production and quality (Fig.3). Articulation of Voice Final modification of the voice occurs in the mouth, nose and throat, where the tongue, palate, cheek and lips are involved in articulation.(speech production) Mechanism of Voice Production: Air Flow and Vocal Fold Vibration Voice production is dependent on the flow of air through the vocal folds and out past the lips. The diagram to the left shows a vertical cross-section through the larynx (voicebox). Below the vocal folds is the trachea, or windpipe, which leads to the lungs. The vocal folds are actually folds of tissue, described in more detail below. In this diagram the vocal folds are separated, as they would be during breathing Just above the vocal folds is a second fold of tissue called the false vocal folds. The false vocal folds are important in preventing substances from entering the trachea during swallowing. They do not play a major role in speech, and, unlike the true vocal folds, they should not come in contact with each other during speech. Above the vocal fold is a floppy cartilaginous tongue-shaped structure called the epiglottis. The epiglottis folds over the opening into the larynx when we swallow, which helps prevent material from getting into the lungs. The position of the vocal folds during speech depends on the type of sounds being made. One grouping of sounds is called "voiced", because their production relies on vibration of the vocal folds. Another grouping is called "voiceless", and for these sounds the vocal folds are usually opened and the sound is produced by another part of mouth and throat. Examples of voiceless sounds are the early parts of the "f" and the "s" sound. These sounds are not produced by the larynx but rather by turbulent air flow in parts of the mouth. Vocal Fold Vibration To make sounds for speech, the vocal folds are first brought together by the muscles of the larynx. While they are closed, the action of the respiratory muscles and the chest wall cause the air pressure immediately below the vocal folds to increase. Eventually the pressure beneath the vocal folds exceeds the pressure holding them together, and a burst of air escapes through the folds. As the air rapidly flows through the larynx, it creates a decreased pressure ( a phenomenon called the Venturi effect) and the vocal folds are brought together. The pressure beneath the folds rises again, and the process repeats itself. The process of rapid opening and closing produces vocal fold vibration that we can see with a stroboscopic examination. Each time the vocal folds open they produce a jet of air which creates a rapid change in air pressure that produces the sounds we use to make speech. It is important to realize that the vocal folds do not produce sound by vibrating like guitar strings. Instead, the sound is produced by the pressure changes created as small jets of air pass through the moving vocal folds. Close Up of the Vocal Folds The microscopic structure of the folds is extremely important both in terms of the way in which sound is produced and in the medical and surgical techniques used to treat voice disorders. The picture to the left shows a close up view of a cross section through one of the vocal folds. You can see that it really is a fold of tissue, and the term "vocal cord" can be somewhat misleading. The vocal fold is covered by a thin layer of tissue called the epithelium. Underlying the mucosa is a second layer called the lamina propria, and under this is the muscle that makes up the body of the vocal fold (it is called the thyroarytenoid muscle; the most medial portion of this muscle is also called the vocalis muscle). The lamina propria is in turn made up of three layers. In the healthy vocal fold the most superficial layer of the lamina propria is quite loose, so that the epithelium can vibrate in a wave-like fashion over the underlying layers. The Mucosal Wave: The diagram to the left shows a schematic of a cross section of the opening and closing of the vocal folds. Notice that the folds do not open all at once, but rather the lower part first begins to open and at a later point in time the upper portion of the folds separate. This complex manner of opening and closing produces what is called the mucosal wave. A good mucosal wave is necessary for the folds to open in a uniform and symmetric fashion. Anything that interferes with this mucosa wave, such as a swelling or a cyst on the folds, disrupts the mucosal wave and causes a worsening in voice quality. When we examine the larynx, the mucosal wave can be studied using a special light source called a strobe light.