Table of Contents

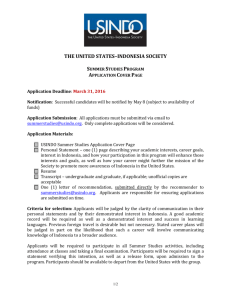

advertisement