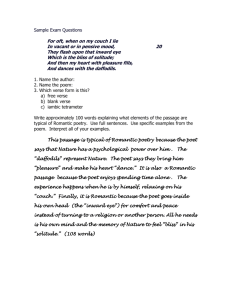

R–10–5 - URI-EnglishLanguageArts

advertisement