Jordan Breslauer

advertisement

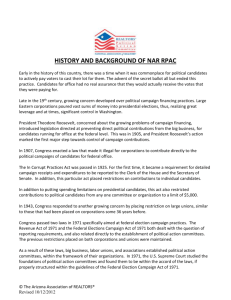

Jordan Breslauer Highland Park High School Committee: Senate Committee on Ethics Topic: Pay- To- Play Delegation: Georgia (Democrat) Throughout American history, “Pay- to- play” has been an important issue never dealt with in its entirety. Pay- to- play is the political term that describes “attempts by municipal bond underwriting businesses to gain influence with political officials who decide which underwriters are awarded the municipality's business.”1 2More generally, Pay-to-Play refers to strategies used by individuals or organization (usually in the form of campaign contributions) to gain inappropriate influence with politicians so that they can financially benefit from political decisions. Pay- to-play has much to do with the political corruption that has occurred and continues to occur in American government. Many American presidents, such as the great General George Washington, wowed important wealthy voters in order to win the first American Presidential election. Andrew Jackson placed 40 % of his financial supporters in positions within the federal bureaucracy. 1 In other words, play to play is the process by which government officials give favorable treatment in government contract auction and other favors to corporations and other interests in return for campaign contributions (from director’s brief) 2 “Pay to Play Definition.” http://www.advfn.com Today, because of the growing number of corporations in America that can donate hard3 and soft money4 to political elections and affairs, the issue has become even more pertinent to the conduct of American government. Contributors who take part in pay- toplay activities inappropriately influence the decisions of many Congressmen and other politicians. Although some state and national legislators have created and passed legislation to prevent excessive pay- to- play activities, little has been done to enforce these regulations to their full extent. In 1907, Congress passed the Tillman Act, “prohibiting corporations and national banks from contributing to federal campaigns.”5 The law also proposed limits on individual contributions. However, money has continued to permeate into the political process, often unfairly influencing publicly elected decision makers. In the more modern version of pay to play, the principal source of political money has shifted form banks to corporations. Starting in the early 1900s, political policy became greatly influenced by corporations contributing large sums of money. The Tillman Act continuously was violated by politicians. It wasn’t until the Teapot Dome Scandal occurred that Congress became convinced that the Tillman Act was not sufficiently Hard money- “A short-term bridge loan that is used for acquisitions, turnaround situations, foreclosures and bankruptcies. Interest rates, although somewhat higher than a normal real estate loan, are less costly than taking on a financial partner or losing the real estate opportunity altogether” (http://www.papkegroup.com 1). “Hard Money is money or anything of value that a political committee receives that satisfies federal contribution limits, source restrictions, and disclosure requirements..” (http://www.campaignfinanceguide.org 1). 3 Soft money- “A money that cannot be depended upon to be available although it may be counted, such as a money pledged as a contribution or that which was received from a source in the past that is only assumed to be available again in the future; money provided in exchange for any type of influence” (http://www.findmehere.com 1). “Soft money is money or anything of value that is given or spent for federal election purposes outside of federal contribution limits, source restrictions, and disclosure requirements. (http://www.campaignfinanceguide.org 1). 5 “In Politics, Money Talks--and Keeps Talking, Despite Reforms.” http://www.campaignfinancesite.org/history/reform3.html 4 effective. They decided more effective legislature was needed to mediate pay to play activities. The Teapot Dome Scandal in 1920 involved companies bribing the Republican Party in exchange for oil reserves. The company clearly had gained influenced over the Republican Party, demonstrating the political corruption that results from pay- to- play activities. Following this scandal, the Federal Corrupt Practices Act of 1925 was created. Unfortunately, the law had a plethora of loopholes and therefore was severely criticized as being ineffective. The next legislature created to limit pay- to- play activity was the Hatch Act of 19406. This act was created by the Republicans, and like all the proceeding acts and laws limiting pay- to- play activities, proved to be ineffective. The general problem had become increasingly evident; congressmen and companies were able to find loopholes in the laws and exploit them. Political Action Committees (PACs) were created giving Congressmen and other politicians yet another way to receive contributions legally. “PACs work by raising money from people employed by a corporation or in a trade union.” PACs allow for corporations to continue their contributions legally because they are affiliated with these groups when they lobby. “In a presidential campaign...the amount a PAC can contribute to a national party is limited to $15,000.... However, PACs can contribute a lot more to state and local parties. In some states the amount is restricted but in others it is not.”7 Thus, ten PACs could donate a total of $150,000 dollars to a presidential campaign, and so on and so forth.8 6 The Hatch Act: Prohibited Federal employees from participating in or contributing to Federal political campaigns. This legislation grew out of FDR's attempts to professionalize government, and from a legislative and public perception that major changes were needed to save the economic viability of the country (http://www.polisci.ccsu.edu 2). 7 “Political Action Committees.” http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/political_action_committees.htm 8 Equation to formulate the amount of money a presidential campaign can receive from PACs: Total money= 15,000X----------- X= the number of PACs. Beginning in the 1940s, controlling the media became extremely important for winning elections. Campaigns needed more money, so more pay- to- play activity and contributions occurred. In 1971, Congress attempted to regulate campaign finance for the first time in forty six years. They created a new act called the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA). FECA initially had a large impact because it, “Changed campaign finance regulations in two major ways. First, in an effort to address rising campaign costs, it limited the amount of money a candidate could give to his or her own campaign and placed limits on the amount a candidate could spend on television advertising. Second, it revised the regulations for disclosing contributions and expenditures by requiring candidates, PACs, and all party committees active in federal elections to file reports on a quarterly basis.”9 Despite these new regulations, spending went from 8 million in 1968 under old legislation to 88 million in 1972 under FECA. In 1974, Congress created the Federal Election Commission (FEC). The FEC had the responsibility of, “administering and enforcing federal campaign finance laws.”10 Amendments were and still are being created by Congress and the Federal Election Commission on FECA. Notably, in 1979, Congress created legislature that, “allowed political parties to spend without limit on getout-the-vote and voter registration activities conducted primarily for a presidential candidate, so long as the funds used to pay for these activities came from monies raised under FECA contribution limits (so-called hard money).”11 FECA restrictions were constantly undermined by political parties who needed money for campaigns. FECA and “A Brief History of Money and Politics.” http://www.campaignfinanceguide.org/guide-34.html Ibid 11 Ibid 9 10 subsequently the FEC took a large hit in effectiveness when they allowed soft money12 contributions to be received by political parties both in states and in national elections.13 The FECA had been infiltrated when the FEC allowed soft money contributions. Congress’ next step towards regulating campaign finance happened in 2002 when it created the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. This Act mainly was a reinforced version of FECA with the exception of some new regulations on some forms of soft money. “First, it reinstituted limits on the sources and size of political party contributions; and second, it regulated how corporate and labor treasury funds could be used in federal elections.”14 In dealing with the issue of soft money, the BCRA resolved the problem by “prohibiting national party committees from raising or spending soft money.”15 Under the new legislation, national party committees only could use hard money raised in accordance with federal contribution limits to pay for their political activities. Although the Federal Government has taken action and has attempted to enforce this legislature to its fullest extent, pay to play activities have risen over the years, and contributions have sky rocketed at an even faster pace. A few states have made efforts to rule out pay to play activities in their states. New Jersey has made great strides in attempts to rid corruption from state government by passing a bill that limits pay to play activity. CMD media explains that the purpose of this bill is to make sure that New Jersey citizens have a, “clean, efficient government at all levels. This measure ensures that local governments have the power to tighten restrictions on public contracts to the level they believe is most appropriate. In other words, this legislation ensures that the towns and 12 Reference to footnote #3 Appendix A: Chart of soft money fundraising 1992-2002 14 Ibid 15 Ibid 13 municipalities have the right to enact their own, more stringent 'pay-to-play' reforms that are stronger than existing state law.”16 The bill is going through some minor amendments but has shown some definite impact throughout the state. New Jersey has shown that it is possible to enforce pay to play legislation by heavily fining corporations that secretly and illegally donate to campaigns. Other states have not made significant strides in rooting out pay to play activity. In fact, “the business of offering short-term, high interest loans – or payday loans” is “legal in 37 states.”17 In 2004, Georgia “shut down the payday loan industry.” However, “a bill was introduced in February returning “payday loans back to the state.” The reason why most states don’t ban pay to play activity is because of the “greedy financial services industry – which includes payday advance lenders, title loan companies, check cashing companies, and pawn shops.”18 Some states want to keep reform and regulation to a minimum because “regulation and reform can effectively wipe out a business in a state, sending its customers across state lines to receive financial services.”1920 While acknowledging this reasoning, the question still remains whether the economy of the states and the federal government is more important than preventing the corruption that results from pay to play activity. Since 2000, money contributed by corporations to campaign funds increasingly has shown its impact on the election process. Since 2000, the “financial services industry has contributed $7.36 million to state-level candidates and party committees in 42 states “Banning New Jersey's 'Pay To Play' History.” http://www.new-jersey.ws/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=4254 17 “Political Payday.” www.followthemoney.org 18 Ibid 19 In other words, reform may be detrimental to economic structure of states and the federal government. 20 “Political Payday.” www.followthemoney.org 16 to date. Winning candidates received more than $4.2 million in contributions while losing candidates received slightly more than $800,000.”21 The message that these data send is the following: the more pay- to- play activity a candidate does, the more likely they are to be victorious in an election. The corporations are now gradually playing larger and larger roles in the election and decision processes of candidates. Currently, “the top 15 contributors combined to give $5.2 million since 1999, accounting for 71 percent of contributions by the industry” to political parties.22These companies usually favor a certain political party. As a result, corruption continues, as both political parties attempt to convince these corporations and contributors to give money to them for their causes. In fact, in January of 2004, the Republican Party held a golf convention in Phoenix for industry executives. The Cox News service reported that, “For around $4,000, industry executives can play golf and have dinner with key congressional Republicans at a Phoenix resort today, then ‘help Congress write its to-do list’ on air pollution and energy policy during the next three days.”23 The article goes on to explain that “money raised by the.... tournament and dinner will be distributed by the Western GOP Majority Committee to Republican campaign organizations according to the invitation.”24 The major corporations that make contributions, or the “big five contributors,” as they are called are25; Advance America26, Cash America International27, Consumer 21 Ibid Ibid 23 “Excess Pay to Play with GOP” http://www.commondreams.org/headlines04/0107-01.htm 24 Ibid 25 The big five are listed in order of largest contributor to smallest (1-5). 26 From “Political Pay Day,” by Scott Jordan, written March 9 th, 2007: “Advance America- Payday lender Advance America donated slightly less than $1 million in 28 states. Hardly partisan, the company gave to both sides of the aisle, slightly favoring Republican candidates and committees with $520,584, while giving Democratic candidates and committees $431,312” (Jordan 2). 22 Lending Alliance28, Illinois Community Currency Exchange Association29, and Check Into Cash30. 31 The top ten recipient states of industry contributions received “threequarters of the $7.36 million doled out by the industry.”32 The top ten recipient states are the following33: Illinois, Florida, California, Georgia, New York, Texas, Virginia, South Carolina, Missouri, and Nevada.34 We, from the state Georgia, have been heavily involved with pay to play activity and in the design of legislation for banning such activities. Our industries and corporations gave a total of $519,173 to political activity. We currently are revisiting a ban on “predatory lending.” In Georgia, “Republican candidates received $246,132 while Democratic candidates received $195,225. Republican state committees received $56,066 while Democratic committees received $19,250. Half of the industry contributions, or From “Political Pay Day,” by Scott Jordan, written March 9 th, 2007: “Cash America International – Payday lender Cash America International doled out a total of $757,418. Democratic candidates and committees received $345,955; Republican candidates and committees received $411,463. The company contributed heavily in five states, giving $212,138 in Texas, $118,450 in Florida, $50,750 in Georgia, and $50,255 in Illinois” (Jordan 2). 27 From “Political Pay Day,” by Scott Jordan, written March 9 th, 2007: “The Consumer Lending Alliance – The Consumer Lending Alliance, an industry trade group, 5 gave more than $600,000 in 15 states. Illinois candidates and committees received more than one-third of that money” (Jordan 3). 28 From “Political Pay Day,” by Scott Jordan, written March 9 th, 2007: “Illinois Community Currency Exchange Association – The Illinois Community Currency Exchange Association, a business that primarily deals with check cashing, gave more than $400,000, contributing $254,100 to Democrats and $149,750 to Republicans” (Jordan 3). 29 From “Political Pay Day,” by Scott Jordan, written March 9 th, 2007: “Check Into Cash – Check Into Cash has been a big player in state campaigns in two states. Candidates and committees in California and Illinois received $95,850 and $101,450, respectively” (Jordan 3). 30 31 Appendix B- Chart of TOP PREDATORY FINANCIAL INDUSTRY CONTRIBUTORS, 1999– 2006 “Political Payday.” www.followthemoney.org The top ten recipient states are listed in order from greatest to least: (1-10). 34 Appendix C: Chart- PREDADORY FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY CONTRIBUTIONS BY STATE, 1999-2006 32 33 $262,363, came in the 2006 election.”35 We have made attempts at banning pay to play actions, but have not yet carried out these plans to the fullest. We feel that the legislation we have attempted to create is full of loop holes. We also have worried how such legislation might negatively impact local businesses in the state. Still, we feel that certain bans on pay to play actions must occur. We support the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), but feel that parts of it now must be strengthened, since pay to play activity still occurs. We also feel that Congress should consider taking clauses of the New Jersey plan and make them into national legislation. We feel that if Congress is able to fix federal pay to play activity, state-based pay to play activity will fix itself in response to Congressional actions. The federal government must lead by example so that the States can do the same, thereby removing corruption and inappropriate corporate influence on the political process. Finally, we from Georgia feel that Congress finally should fix the problems left by FECA. Congress must put an end to soft money contributions and campaign contributions must be limited. Corporations and unions should be banned from contributions. However, PACs should still be allowed to contribute to campaigns. As the senate committee on ethics, we must rid corruption from our capital city as well as from our states. When our founding fathers created the Constitution and fought the Revolutionary War, they wanted to establish a country free of corruption. If pay to play activity continues, the country will not meet the expectations we have set forth for it. 35 “Political Payday.” www.followthemoney.org Appendix A: Bar Graph of Soft Money Fundraising (1992-2002) Appendix B: TOP PREDATORY FINANCIAL INDUSTRY CONTRIBUTORS, 1999–2006 COMPANY Advance America Cash America International Consumer Lending Alliance Illinois Community Currency Exchange Association Check Into Cash Amscot Corporation Check Cashers Association of New York/Check PAC Select Management Resources Check ‘n Go QC Financial Services Moneytree 409 Group Anderson Financial Services/LoanMax Dollar Financial Group California Financial Service Providers TOTAL $955,896 $757,418 $604,592 $403,850 $361,000 $359,900 $282,124 $230,104 $211,650 $202,600 $194,079 $183,700 $164,571 $160,200 $152,600 FINAL TOTAL----- $5,224,284 Appendix C: PREDADORY FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY CONTRIBUTIONS BY STATE, 1999-2006 STATE Illinois Florida California Georgia New York Texas Virginia South Carolina Missouri Nevada Oregon Tennessee Louisiana Indiana New Jersey Arkansas New Mexico Kansas Washington Alabama Mississippi Idaho Utah North Carolina Ohio Oklahoma Michigan Maryland Colorado Pennsylvania New Hampshire Arizona Maine Kentucky Nebraska Delaware South Dakota West Virginia TOTAL $1,130,385 $994,125 $837,673 $519,173 $469,895 $394,248 $304,685 $293,225 $260,333 $207,450 $206,329 $191,079 $170,286 $168,495 $148,350 $134,150 $130,200 $121,925 $120,725 $105,345 $76,125 $73,500 $72,400 $43,800 $34,650 $32,300 $29,600 $29,013 $19,215 $11,656 $10,450 $10,000 $9,100 $6,600 $6,220 $3,650 $1,500 $1,250 Wisconsin Hawaii Connecticut Iowa $1,000 $650 $500 $250 FINAL TOTAL: $7,364,905 Bibliography Padilla, Steve “In Politics, Money Talks--and Keeps Talking, Despite Reforms,” http://www.campaignfinancesite.org/, Hoover Institution: Public Policy Inquiry Campaign Finance History Los Angeles Times, 2001, <http://www.campaignfinancesite.org/history/reform3.html> Drew, James and Wilkinson, Mike “Pay-to-play law never enforced, critics say Loopholes let donors avoid serious scrutiny,” http://www.toledoblade.com/, Coingate, Toleoblade.com News, 2007, <http://www.toledoblade.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20050925/SRRARECOINS/30 9250003> “Teapot Dome Scandal,” http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/, 2004, <http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAteapot.htm> “Early Twentieth Century Timeline,” http://www.polisci.ccsu.edu/, 2002, <http://www.polisci.ccsu.edu/trieb/early.HTM> Harrington, Shannon D.; Riley, Clint; and Pillets, Jeff; “Calls to reform 'pay to play' go unheeded,” http://www.northjersey.com/, North Jersey Media Group, 2003, <http://www.northjersey.com/page.php?qstr=eXJpcnk3ZjcxN2Y3dnFlZUVFeXkyJmZn YmVsN2Y3dnFlZUVFeXk2NDY4ODgw> “Political Action Committees,” http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/, 2000-2007, <http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/political_action_committees.htm> Senator Vitale, Joseph “Banning New Jersey's 'Pay To Play' History,” http://www.newjersey.ws/, CMD Media and Atom Tabloid, 2004, <http://www.newjersey.ws/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=4254> “A Brief History of Money and Politics,” http://www.campaignfinanceguide.org/, Campaign Finance Guide: Federal Campaign Finance Laws, 2007, <http://www.campaignfinanceguide.org/guide-34.html> Jordan, Scott “Political Payday,” National Institute on Money in State Politics, 03 March 07, <www.followthemoney.org>