Assignment #4: Arguing a Position

advertisement

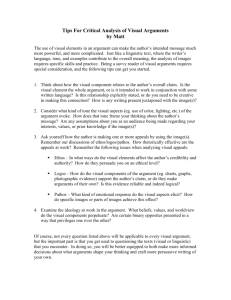

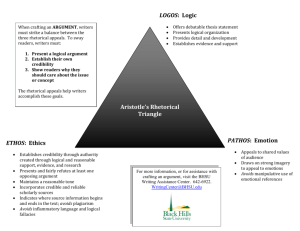

Assignment #4: Arguing a Position Due Dates: 1st Draft: Final Draft: Friday, April 16 Monday, April 19 Background to the assignment In your first assignment, the rhetorical analysis, we examined closely the ways in which writers put arguments together by making rhetorical choices and using specific rhetorical features that combine to persuade an audience. Taking this even one step further, we went beyond analysis to evaluation, as part of your assignment was to decide if the writer’s argument was, indeed, effective. This exercise in rhetoric was, in part, meant to get you thinking about composing your own arguments— arguments that are effectively persuasive. In the second and third assignments, we learned about academic conversations, research problems, and how members of specific academic disciplines argue about issues that interest them and are important to their respective disciplines. For many of us, the subtle stance required by the literature review assignment was a challenge because, as Bullock states in the NFG, “everything we say or do presents some kind of argument, takes some kind of position” (82). For this assignment, you will argue a position from your own informed perspective on an issue relating to your discipline. Doing so, you will have to draw on what you’ve learned about rhetorical appeals (logos, ethos, pathos), organizing information, and using sources to compose an effective argument. At this point, the groundwork for your research and topic should already be laid for you from your work on the previous assignments. Now it’s time to work on refining your position on the issue (making an argumentative claim about it) and continuing your research. It is important to note, however, that argumentation is not simply spouting off on an issue: you must have convincing support gained through research and careful consideration of other positions in order to make an effective argument. The writing assignment Your assignment is to write an argumentative essay (5-7 pages) in which you argue a position on the issue relating to your field that you developed through your research for the proposal, annotated bibliography, and literature review. You’ll want to think of your argument as part of the larger academic conversation that is taking place about the issue within its discipline. To do so, you will need to continue to find out what has been said on the topic (by extending the research and reading you began in your annotated bibliography and literature review) in order to find a way to join the ongoing discussion. Your paper should include a minimum of five academic sources. Requirements for Argument Purpose To argue a position on an issue that has its foundation in a specific academic discipline. Audience You are writing for an audience that does not necessarily share your opinion on the issue or that does not have an opinion on it at all (i.e. you are trying to persuade your audience to believe what you believe while at the same time defending your position). Genre Argument. Stance Your opinion on your chosen subject. Media/Design Your argument should be 5-7 pages in length. It should include a title page and be typed using doublespaced, 12-point Times New Roman font and following MLA guidelines. Nota Bene: Academic papers (and specifically academic arguments) take into account what “they say”—it’s not just a matter of coming up with a topic and writing about it from scratch or finding random or general sources on the Internet. You must be able to position yourself—your ideas—within others’ opinions and research. This doesn’t always mean that you disagree—it means that you might qualify some aspect of their position or agree with some of their points, but not with others. And it is important to remember that those opinions and research to which you want to be responding are typically found in academic libraries/databases and are often specific to and developed within a particular discourse community. This is why we completed the annotated bibliography and literature review assignments in a particular academic discipline—in order to write our arguments within an already established conversation. That said, as you compose your argument, you’ll want to be thinking of the work you are doing as genuine scholarship, as if adding to that ongoing conversation. GETTING STARTED… Refine your topic (and your position on the topic) – You should already have decided upon a topic on which you will be focusing for your argument paper through the last two assignments. You will now need to refine your topic by taking a position on the issue and coming up with an arguable claim that will essentially serve as your thesis. A good claim will respond to an open-ended question beginning with “how” or “what” rather than a closed question beginning with “should” (eg. not “Should capital punishment be prohibited?” but rather “What are the ethical implications of capital punishment in a democratic society?”). Continue to find out what has been said about the issue – Extend the research you began in your bibliography and continued to develop in your literature review, as you’ll need to reference a minimum of five academic sources in your paper. You’ve probably already found several useful sources, and one good way to find more (besides continuing research in the library catalogue and databases) is to consult the bibliographies of the sources you already have. Also keep in mind that an effective argument considers in full what those who oppose its views might say—this means that you will need to find some sources that don’t necessarily agree with your position. Remember rhetorical appeals – Keep in mind the work we did while analyzing Diamond’s argument and his use of classical rhetorical appeals (logos, ethos, and pathos). You should continually be considering how you might employ these appeals in your own argument to reach your audience. This is not an attack – Just as Bullock states in the NFG, “Arguments can stand or fall on the way readers perceive the writer . . . readers need to trust the person who’s making the argument” (94). Choose your tone accordingly. Finally – Arguments should be in present tense. You can use first person as needed, and anecdotal evidence (i.e. personal experience) is acceptable, but do so in moderation and with discretion.