Chapter 8 homework and notes

advertisement

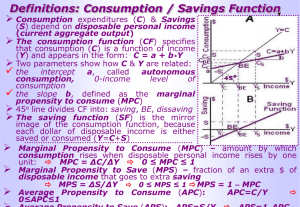

Basic Macroeconomic Relationships CHAPTER NINE BASIC MACROECONOMIC RELATIONSHIPS CHAPTER OVERVIEW The central purpose of this chapter is to introduce three basic macroeconomic relationships that will help us organize our thinking about macroeconomic theories and controversies: First, the focus is on the income-consumption and income-saving relationships. Second, the relationship between the interest rate and investment is examined. Finally, the multiplier concept is developed, relating changes in spending to changes in output. All of this is done outside the formal framework of the Aggregate Expenditures model, which is developed in Chapter 10. WHAT’S NEW This chapter has undergone substantial revision, combining parts of both Chapters 9 and 10 from the previous edition. The Keynesian Aggregate Expenditures (AE) model is no longer introduced in this chapter, but the underlying relationships and important conclusions are still presented here, including the basic consumption and saving functions. Those wanting to discuss those relationships without developing the AE model can omit Chapter 10 and proceed directly from this chapter to the Aggregate Demand/Aggregate Supply model in Chapter 11. The multiplier effect is now included in this chapter but is developed without the benefit of the AE model (although the basic equations, including the marginal propensities, are presented). In discussion of the multiplier, the terms “simple multiplier” and “complex multiplier” have been dropped. The text now identifies the multiplier (as presented in examples) and the “actual multiplier,” although the latter is not presented as a formal term for students to learn. There are a number of other minor edits. The discussion of the wealth effect is modified, including a “Consider This” box, and has an example of a “reverse wealth effect.” The real interest rate is now identified as a determinant, albeit a minor one, of consumption spending. The discussion of the investment schedule (relating investment and real GDP) now appears in Chapter 10. There is a new “Last Word” on the multiplier (which appeared in the previous edition in Chapter 10). End-of-chapter-questions are now a combination of questions from the last edition’s Chapter 9 and 10 questions, revised as needed to reflect content changes. INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES After completing this chapter, students should be able to 1. Describe the income-consumption and income-saving relationships. 2. Recognize, construct, and explain the consumption and saving schedules. 3. Identify the determinants of the location of the consumption and saving schedules. 4. Calculate and differentiate between the average and marginal propensities to consume (and save). 5. Describe the relationship between the interest rate, expected rate of return, and investment. 6. Identify the determinants of investment and construct an investment demand curve. 7. Identify the factors that may cause a shift in the investment-demand curve. 135 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships 8. Describe the reasons for the instability in investment spending. 9. Provide an intuitive explanation of the multiplier effect. 10. Calculate the multiplier and changes in real GDP given information about changes in spending and marginal propensities. 11. Discuss why the actual multiplier may differ from the theoretical examples. COMMENTS AND TEACHING SUGGESTIONS 1. Regardless of whether you develop the multiplier theoretically or more intuitively, if you require students to calculate multiplier effects, expect to give them lots of practice. As part of that, you may want to give them “detective” work – “If we know that real GDP changed by $100 billion and spending changed by $25 billion, what can we conclude about the multiplier and MPC?” 2. The multiplier concept can be demonstrated effectively by a role-playing exercise in which you have students pretend that one row (group) of students are construction workers who benefit from a $1 million increase in investment spending. (Some instructors use an oversized paper $1-million bill.) If their MPC is .9, then they will spend $900,000 of this at stores “owned” by a second row (group) of students, who will in turn spend $810,000 or .9 x $900,000. At the end of the exercise, each row can add up its new income and it will be well in excess of the initial $1 million. In fact, if played out to its conclusion, the final change in GDP should approximate $10 million, given the MPS is .1 in this example. If you decide to use an oversized paper $1-million bill, then students will have to clip off one-tenth of it at every stage to represent saving. By the end of the process, each row (group) of students has seen its income increase by nine-tenths of what the previous group received. Adding up all of these increases illustrates the idea that the original $1 million increase in spending has resulted in many times that amount in terms of the students’ increased incomes. Obviously, you won’t be able to illustrate the final multiplier, but it should give them a good idea of how the final multiplier could be equal to 10 in this example. In other words, if the process were carried to its conclusion, the original $1 million of new investment would result in a $10 million increase in student incomes and $10 million of new saving. If you don’t want to use the prop, students are good at imagining that this could happen if you’ll simply ask them to imagine that a new $1 million injection of investment spending (or government or export sales) occurs, and then go through the chain of events described above. 3. Note that the multiplier effect can work in reverse as well as in the forward direction. The closing of a military base or a factory shutting down has a multiplied negative impact on the local community, reducing retail sales and placing a hardship on other businesses. Ask students to offer examples of the multiplier effect that they have witnessed. They enjoy making up their own versions of Buchwald’s Last Word for this chapter. 4. Data to update Figure 9-1 may be found in the most recent issue of Survey of Current Business or Economic Indicators. Web-based questions at the end of the chapter also point to sources. 5. Investment expenditures are the most volatile segment of aggregate expenditures. Ask students to research a particular industry to find out what factors are most likely to influence investment decisions for that industry, or have students interview a local business manager or owner about their decision to add capital equipment. Make a list of the factors that they consider when making their decisions. Are they similar to the reasons given in the text? How were they different? STUDENT STUMBLING BLOCKS 1. If your class is filled with struggling students consider using only one “macro model.” It is very difficult for beginning students to switch from one set of assumptions to another. The concept of 136 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships equilibrium can be presented using Aggregate Expenditures or the AD-AS model presented in Chapter 11. The model in this chapter uses income as the main determinant. AD-AS emphasizes the price level. An emphasis on only one model may help students understand the macro economy better. This chapter may help you gauge whether or not to skip Chapter 10. 2. Students sometimes get so caught up in the theory that they forget the basic relationships. To help them remember even simple things like MPC + MPS = 1, remind them that there are two things they can do with their disposable income – spend it or save it. Invariably someone will ask, “What about paying off credit cards (or other forms of debt)? Isn’t that spending?” You can either respond then or attempt to preempt the question by explaining that repayment of debt is merely saving “after the fact.” It is also an opportunity to review past material. If someone suggests that they can also pay taxes, you can remind them that disposable income is after-tax income. 3. The discussion of the income and consumption relationship is a good opportunity to remind students about the “fallacy of composition.” Unfortunately it is also a potential stumbling block. When you discuss the marginal propensities, for example, it is on the one hand helpful to individualize the experience – “If you received an extra dollar, how much of it would you spend?” On the other hand, how students answer such questions may cloud their ability to reason through what to expect in the aggregate. You will need to remind students at times that they’re examining aggregate behavior and that they can’t necessarily generalize from their individual experience. LECTURE NOTES I. Introduction—What Are the Basic Macro Relationships? A. Previously we identified macroeconomic issues of growth, business cycles, recession, and inflation. Here we begin to develop tools to explain these events. B. This chapter focuses on the three basic macroeconomic relationships. 1. Income and consumption, and income and saving. 2. The interest rate and investment. 3. Changes in spending and changes in output. II. The Income-Consumption and Income-Saving Relationships A. Disposable income is the most important determinant of consumer spending (see Figure 9-1 in text which presents historical evidence). B. What is not spent is called saving. C. Figure 9-1 represents graphically the recent historical relationship between disposable income (DI), consumption (C), and saving (S) in the United States. 1. A 45-degree line represents all points where consumer spending is equal to disposable income; other points represent actual C, DI relationships for each year from 1980-2002. 2. If the actual graph of the relationship between consumption and income is below the 45degree line, then the difference must represent the amount of income that is saved. 3. In 1996 consumption was $5406 billion and disposable income was $5678 billion. Hence, saving was $272 billion. 4. Some conclusions can be drawn. a. Households consume a large portion of their disposable income. b. Both consumption and saving are directly related to the level of income. 137 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships D. The consumption schedule. 1. A hypothetical consumption schedule (Table 9-1 and Key Graph 9-2a) shows that households spend a larger proportion of a small income than of a large income. 2. A hypothetical saving schedule (Table 1, column 3) is illustrated in Key Graph 9-2b. 3. Note that “dissaving” occurs at low levels of disposable income, where consumption exceeds income and households must borrow or use up some of their wealth. E. Average and marginal propensities to consume and save. 1. Define average propensity to consume (APC) as the fraction or % of income consumed (APC = consumption/income). See Column 4 in Table 9-1. 2. Define average propensity to save (APS) as the fraction or % of income saved (APS = saving/income). See Column 5 in Table 9-1. 3. Global Perspective 9-1 shows the APCs for several nations in 2000. Note the high APCs for the U.S., Canada, and the United Kingdom. 4. Marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the fraction or proportion of any change in income that is consumed. (MPC = change in consumption/change in income.) See Column 6 in Table 9-1. 5. Marginal propensity to save (MPS) is the fraction or proportion of any change in income that is saved. (MPS = change in saving/change in income.) See Column 7 in Table 9-1. 6. Note that APC + APS = 1 and MPC + MPS = 1. 7. Note that Figure 9-3 illustrates that MPC is the slope of the consumption schedule, and MPS is the slope of the saving schedule. 8. Test Yourself: Try the Self-Quiz below Key Graph 9-2. F. Nonincome determinants of consumption and saving can cause people to spend or save more or less at various income levels, although the level of income is the basic determinant. 1. Wealth: An increase in wealth shifts the consumption schedule up and saving schedule down. In recent years major fluctuations in stock market values have increased the importance of this wealth effect. A “reverse wealth effect” occurred in 2000 and 2001, when stock prices fell dramatically. CONSIDER THIS … What Wealth Effect. 2. Expectations: Changes in expected future prices or wealth can affect consumption spending today. 3. Real interest rates: Declining interest rates increase the incentive to borrow and consume, and reduce the incentive to save. Because many household expenditures are not interest sensitive – the light bill, groceries, etc. – the effect of interest rate changes on spending are modest. 4. Household debt: Lower debt levels shift consumption schedule up and saving schedule down. 5. Taxation: Lower taxes will shift both schedules up since taxation affects both spending and saving; vice versa for higher taxes. G. Terminology, shifts, and stability. See Figure 9-4. 1. Terminology: Movement from one point to another on a given schedule is called a change in amount consumed; a shift in the schedule is called a change in consumption schedule. 138 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships 2. Schedule shifts: Consumption and saving schedules will always shift in opposite directions unless a shift is caused by a tax change. 3. Stability: Economists believe that consumption and saving schedules are generally stable unless deliberately shifted by government action. III. The Interest Rate – Investment Relationship A. Investment consists of spending on new plants, capital equipment, machinery, inventories, construction, etc. 1. The investment decision weighs marginal benefits and marginal costs. 2. The expected rate of return is the marginal benefit and the interest rate – the cost of borrowing funds – represents the marginal cost. B. The expected rate of return is found by comparing the expected economic profit (total revenue minus total cost) to cost of investment to get the expected rate of return. The text’s example gives $100 expected profit on a $1000 investment, for a 10% expected rate of return. Thus, the business would not want to pay more than a 10% interest rate on investment. Remember that the expected rate of return is not a guaranteed rate of return. Investment carries risk. C. The real interest rate, i (nominal rate corrected for expected inflation), determines the cost of investment. 1. The interest rate represents either the cost of borrowed funds or the opportunity cost of investing your own funds, which is income forgone. 2. If real interest rate exceeds the expected rate of return, the investment should not be made. D. Investment demand schedule, or curve, shows an inverse relationship between the interest rate and amount of investment. 1. As long as expected return exceeds interest rate, the investment is expected to be profitable (see Table 9-2 example). 2. Key Graph 9-5 shows the relationship when the investment rule is followed. Fewer projects are expected to provide high return, so less will be invested if interest rates are high. 3. Test yourself with Quick Quiz 9-5. E. Shifts in investment demand occur when any determinant apart from the interest rate changes. 1. Greater expected returns create more investment demand; shift curve to right. The reverse causes a leftward shift. a. Acquisition, maintenance, and operating costs of capital goods may change. Higher costs lower the expected return. b. Business taxes may change. Increased taxes lower the expected return. c. Technology may change. Technological change often involves lower costs, which would increase expected returns. d. Stock of capital goods on hand will affect new investment. If there is abundant idle capital on hand because of weak demand or recent investment, new investments would be less profitable. e. Expectations about future economic and political conditions, both in the aggregate and in certain specific markets, can change the view of expected profits. 139 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships F. Investment is a very unstable type of spending; I is more volatile than GDP (See Figure 9-7). 1. Capital goods are durable, so spending can be postponed or not. This is unpredictable. 2. Innovation occurs irregularly. 3. Profits vary considerably. 4. Expectations can be easily changed. IV. The Multiplier Effect A. Changes in spending ripple through the economy to generate event larger changes in real GDP. This is called the multiplier effect. 1. Multiplier = change in real GDP / initial change in spending. Alternatively, it can be rearranged to read Change in real GDP = initial change in spending x multiplier. 2. Three points to remember about the multiplier: a. The initial change in spending is usually associated with investment because it is so volatile. b. The initial change refers to an upshift or downshift in the aggregate expenditures schedule due to a change in one of its components, like investment. c. The multiplier works in both directions (up or down). B. The multiplier is based on two facts. 1. The economy has continuous flows of expenditures and income—a ripple effect—in which income received by Grant comes from money spent by Battaglia. Battaglia’s income, in turn, came from money spent by Mendoza, and so forth. 2. Any change in income will cause both consumption and saving to vary in the same direction as the initial change in income, and by a fraction of that change. a. The fraction of the change in income that is spent is called the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). b. The fraction of the change in income that is saved is called the marginal propensity to save (MPS). c. This is illustrated in Table 9-3, and Figure 9-8 that is derived from the Table. C. The size of the MPC and the multiplier are directly related; the size of the MPS and the multiplier are inversely related. See Figure 9-9 for an illustration of this point. In equation form Multiplier = 1/MPS or 1/(1-MPC). D. The significance of the multiplier is that a small change in investment plans or consumptionsaving plans can trigger a much larger change in the equilibrium level of GDP. E. The simple multiplier given above can be generalized to include other “leakages” from the spending flow besides savings. For example, the actual multiplier is derived by including taxes and imports as well as savings in the equation. In other words, the denominator is the fraction of a change in income not spent on domestic output. (Key Question 9) V. LAST WORD: Squaring the Economic Circle A. Humorist Art Buchwald illustrates the concept of the multiplier with this funny essay. B. Hofberger, a Chevy salesman in Tomcat, Va., called up Littleton of Littleton Menswear & Haberdashery, and told him that a new Nova had been set aside for Littleton and his wife. 140 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships C. Littleton said he was sorry, but he couldn’t buy a car because he and Mrs. Littleton were getting a divorce. D. Soon afterward, Bedcheck the painter called Hofberger to ask when to begin painting the Hofbergers’ home. Hofberger said he couldn’t, because Littleton was getting a divorce, not buying a new car, and, therefore, Hofberger could not afford to paint his house. E. When Bedcheck went home that evening, he told his wife to return their new television set to Gladstone’s TV store. When she returned it the next day, Gladstone immediately called his travel agent and canceled his trip. He said he couldn’t go because Bedcheck returned the TV set because Hofberger didn’t sell a car to Littleton because Littletons are divorcing. F. Sandstorm, the travel agent, tore up Gladstone’s plane tickets, and immediately called his banker, Gripsholm, to tell him that he couldn’t pay back his loan that month. G. When Rudemaker came to the bank to borrow money for a new kitchen for his restaurant, the banker told him that he had no money to lend because Sandstorm had not repaid his loan yet. H. Rudemaker called his contractor, Eagleton, who had to lay off eight men. I. Meanwhile, General Motors announced it would give a rebate on its new models. Hofberger called Littleton to tell him that he could probably afford a car even with the divorce. Littleton said that he and his wife had made up and were not divorcing. However, his business was so lousy that he couldn’t afford a car now. His regular customers, Bedcheck, Gladstone, Sandstorm, Gripsholm, Rudemaker, and Eagleton had not been in for over a month! ANSWERS TO END-OF-CHAPTER QUESTIONS 9-1 Very briefly summarize the relationships shown by (a) the consumption schedule, (b) the saving schedule, (c) the investment demand curve, and (d) the multiplier effect. Which of these relationships are direct (positive) relationships and which are inverse (negative) relationships? Why are consumption and saving in the United States greater today than they were a decade ago. (a) The consumption schedule or curve shows how much households plan to consume at various levels of disposable income at a specific point in time, assuming there is no change in the nonincome determinants of consumption, namely, wealth, the price level, interest rates, expectations, indebtedness, and taxes. A change in disposable income causes movement along a given consumption curve. A change in a nonincome determinant causes the entire schedule or curve to shift. (b) The saving schedule or curve shows how much households plan to save at various levels of disposable income at a specific point in time, assuming there is no change in the nonincome determinants of saving, namely, wealth, the price level, interest rates, expectations, indebtedness, and taxes. A change in disposable income causes movement along a given saving curve. A change in a nonincome determinant causes the entire schedule or curve to shift. (c) The investment demand curve shows how much will be invested at all possible interest rates, given the expected rate of net profit from the proposed investments, assuming there is no change in the noninterest-rate determinants of investment, namely, acquisition, maintenance, operating costs, business taxes, technological change, the stock of capital goods on hand, and expectations. A change in any of these will affect the expected rate of net profit and shift the curve. A change in the interest rate will cause movement along a given curve. 141 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships (d) The multiplier effect shows how an initial change in spending can flow through the system to generate a larger change in GDP. Consumption and saving are directly (positively) related to income. Investment is inversely (negatively) related to the real interest rate. The multiplier directly relates changes in spending to changes in GDP. Consumption and saving are greater today primarily because income is greater. Note that this does not necessarily mean that per capita consumption and saving have risen; both GDP and population have risen over the past decade. 9-2 Precisely how do the APC and the MPC differ? Why must the sum of the MPC and the MPS equal 1? What are the basic determinants of the consumption and saving schedules? Of your personal level of consumption? APC is an average whereby total spending on consumption (C) is compared to total income (Y): APC = C/Y. MPC refers to changes in spending and income at the margin. Here we compare a change in consumer spending to a change in income: MPC = change in C/change in Y. When your income changes there are only two possible options regarding what to do with it: You either spend it or you save it. MPC is the fraction of the change in income spent; therefore, the fraction not spent must be saved and this is the MPS. The change in the dollars spent or saved will appear in the numerator and together they must add to the total change in income. Since the denominator is the total change in income, the sum of the MPC and MPS is one. The basic determinants of the consumption and saving schedules are the levels of income and output. Once the schedules are set, the determinants of where the schedules are located would be the amount of household wealth (the more wealth, the more is spent at each income level); expectations of future income, the real interest rate, prices and product availability; the relative size of consumer debt; and the amount of taxation. Chances are that most of us would answer that our income is the basic determinant of our levels of spending and saving, but a few may have low incomes, with large family wealth that determines the level of spending. Likewise, other factors may enter into the pattern, as listed in the preceding paragraph. Answers will vary depending on the student’s situation. 9-3 Explain how each of the following will affect the consumption and saving schedules or the investment schedule: a. A large increase in the value of real estate, including private houses. b. A decline in the real interest rate. c. A sharp, sustained decline in stock prices. d. An increase in the rate of population growth. e. The development of a cheaper method of manufacturing computer chips. f. A sizable increase in the retirement age for collecting Social Security benefits. g. The expectation that mild inflation will persist in the next decade. h. An increase in the Federal personal income tax. (a) If this simply means households have become more wealthy, then consumption will increase at each income level. The consumption schedule should shift upward and the saving schedule shift downward. The investment schedule may shift rightward if owners of existing homes sell them and invest in construction of new homes more than previously. (b) The decline in the real interest rate will increase interest-sensitive consumer spending; the consumption schedule will shift up and the saving schedule down. Investors will increase 142 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships investment as they move down the investment-demand curve; the investment schedule will shift upward. (c) A sharp decline in stock prices can be expected to decrease consumer spending because of the decrease in wealth; the consumption schedule shifts down and the saving schedule upward. Because of the depressed share prices and the number of speculators forced out of the market, it will be harder to float new issues on the stock market. Therefore, the investment schedule will shift downward. (d) The increase in the rate of population growth will, over time, increase the rate of income growth. In itself this will not shift any of the schedules but will lead to movement upward to the right along the upward sloping investment schedule. (e) This innovation will in itself shift the investment schedule upward. Also, as the innovation starts to lower the costs of producing everything using these chips, prices will decrease leading to increased quantities demanded. This, again, could shift the investment schedule upward. (f) The postponement of benefits may cause households to save more if they planned to retire before they qualify for benefits; the saving schedule will shift upward, the consumption schedule downward. This impact is uncertain, however, if people continue to work and earn productive incomes. (g) If this is a new expectation, the consumption schedule will shift upwards and the saving schedule downwards until people have stocked up enough. After about a year, if the mild inflation is not increasing, the household schedules will revert to where they were before. (h) Because this reduces disposable income, consumption will decline in proportion to the marginal propensity to consume. Consumption will be less at each level of real output, and so the curve shifts down. The saving schedule will also fall because the disposable income has decreased at each level of output, so less would be saved. 9-4 Explain why an upward shift in the consumption schedule typically involves an equal downshift in the saving schedule. What is the exception to this relationship? If, by definition, all that you can do with your income is use it for consumption or saving, then if you consume more out of any given income, you will necessarily save less. And if you consume less, you will save more. This being so, when your consumption schedule shifts upward (meaning you are consuming more out of any given income), your saving schedule shifts downward (meaning you are consuming less out of the same given income). The exception is a change in personal taxes. When these change, your disposable income changes, and, therefore, your consumption and saving both change in the same direction and opposite to the change in taxes. If your MPC, say, is 0.9, then your MPS is 0.1. Now, if your taxes increase by $100, your consumption will decrease by $90 and your saving will decrease by $10. 9-5 (Key Question) Complete the accompanying table. 143 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships Level of Output and income (GDP = DI) Consumption Saving APC APS MPC MPS $240 $ _____ $-4 _____ _____ _____ _____ 260 $ _____ 0 _____ _____ _____ _____ 280 $ _____ 4 _____ _____ _____ _____ 300 $ _____ 8 _____ _____ _____ _____ 320 $ _____ 12 _____ _____ _____ _____ 340 $ _____ 16 _____ _____ _____ _____ 360 $ _____ 20 _____ _____ _____ _____ 380 $ _____ 24 _____ _____ _____ _____ 400 $ _____ 28 _____ _____ _____ _____ Data for completing the table (top to bottom). Consumption: $244; $260; $276; $292; $308; $324; $340; $356; $372. APC: 1.02; 1.00; .99; .97; .96; .95; .94; .94; .93. APS: -.02; .00; .01; .03; .04; .05; .06; .06; .07. MPC: .80 throughout. MPS: .20 throughout. a. Show the consumption and saving schedules graphically. b. Find the break-even level of income. How is it possible for households to dissave at very low-income levels? c. If the proportion of total income consumed (APC) decreases and the proportion saved (APS) increases as income rises, explain both verbally and graphically how the MPC and MPS can be constant at various levels of income. (a) See the graphs. Question 9-5a 420 400 Consumption 380 C 360 340 320 300 Break-Even Income 280 Question 9-5a 260 240 30 220 25 220 45 240 S 260 280 300 340 360 380 400 420 Real GDP 20 Savings 320 15 10 5 0 220 -5 240 260 280 300 320 144 -10 Real GDP 340 360 380 400 420 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships (b) Break-even income = $260. Households dissave borrowing or using past savings. (c) Technically, the APC diminishes and the APS increases because the consumption and saving schedules have positive and negative vertical intercepts, respectively. (Appendix to Chapter 1). MPC and MPS measure changes in consumption and saving as income changes; they are the slopes of the consumption and saving schedules. For straight-line consumption and saving schedules, these slopes do not change as the level of income changes; the slopes and thus the MPC and MPS remain constant. 9-6 What are the basic determinants of investment? Explain the relationship between the real interest rate and the level of investment. Why is investment spending unstable? How is it possible for investment spending to increase even in a period in which the real interest rate rises? The basic determinants of investment are the expected rate of return (net profit) that businesses hope to realize from investment spending, and the real rate of interest. When the real interest rate rises, investment decreases; and when the real interest rate drops, investment increases—other things equal in both cases. The reason for this relationship is that it makes sense to borrow money at, say, 10 percent, if the expected rate of net profit is higher than 10 percent, for then one makes a profit on the borrowed money. But if the expected rate of net profit is less than 10 percent, borrowing the money would be expected to result in a negative rate of return on the borrowed money. Even if the firm has money of its own to invest, the principle still holds: The firm would not be maximizing profit if it used its own money to carry out an investment returning, say, 9 percent when it could lend the money at an interest rate of 10 percent. Investment is unstable because, unlike most consumption, it can be put off. In good times, with demand strong and rising, businesses will bring in more machines and replace old ones. In times of economic downturn, no new machines will be ordered. A firm can continue for years with, say, a tenth of the investment it was carrying out in the boom. Very few families could cut their consumption so drastically. New business ideas and the innovations that spring from them do not come at a constant rate. This is another reason for the irregularity of investment. Profits and the expectations of profits also vary. Since profits, in the absence of easy access to borrowed money, are essential for investment and since, moreover, the object of investment is to make a profit, investment, too, must vary. As long as expected rates of return rise faster than real interest rates, investment spending may increase. This is most likely to occur during periods of economic expansion. 9-7 (Key Question) Suppose a handbill publisher can buy a new duplicating machine for $500 and that the duplicator has a 1-year life. The machine is expected to contribute $550 to the year’s net revenue. What is the expected rate of return? If the real interest rate at which funds can be 145 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships borrowed to purchase the machine is 8 percent, will the publisher choose to invest in the machine? Explain. The expected rate of return is 10% ($50 expected profit/$500 cost of machine). The $50 expected profit comes from the net revenue of $550 less the $500 cost of the machine. If the real interest rate is 8%, the publisher will invest in the machine as the expected profit (marginal benefit) from the investment exceeds the cost of borrowing the funds (marginal cost). 9-8 (Key Question) Assume there are no investment projects in the economy that yield an expected rate of return of 25 percent or more. But suppose there are $10 billion of investment projects yielding an expected rate of return of between 20 and 25 percent; another $10 billion yielding between 15 and 20 percent; another $10 billion between 10 and 15 percent; and so forth. Cumulate these data and present them graphically, putting the expected rate of net return on the vertical axis and the amount of investment on the horizontal axis. What will be the equilibrium level of aggregate investment if the real interest rate is (a) 15 percent, (b) 10 percent, and (c) 5 percent? Explain why this curve is the investment-demand curve. See the graph below. Aggregate investment: (a) $20 billion; (b) $30 billion; (c) $40 billion. This is the investment-demand curve because we have applied the rule of undertaking all investment up to the point where the expected rate of return, r, equals the interest rate, i. 9-9 (Key Question) What is the multiplier effect? What relationship does the MPC bear to the size of the multiplier? The MPS? What will the multiplier be when the MPS is 0, .4, .6, and 1? What will it be when the MPC is 1, .9, .67, .5, and 0? How much of a change in GDP will result if firms increase their level of investment by $8 billion and the MPC is .80? If the MPC is .67? The multiplier effect describes how an initial change in spending ripples through the economy to generate a larger change in real GDP. It occurs because of the interconnectedness of the economy, where a change in Haslett’s spending will generate more income for Davidic, who will in turn spend more, generating additional income for Grimes. The MPC is directly (positively) related to the size of the multiplier. The MPS is inversely (negatively) related to the size of the multiplier. The multiplier values for the MPS values: undefined, 2.5, 1.67, and 0. The multiplier values for the MPC values: undefined, 10, 3 (approx. actually 3.03), 2, 0. If MPC is .80, change in GDP is $40 billion (5 x $8 = $40) 146 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships If MPC is .67, change in GDP is $24 billion (approximately) (3 x $8 = $24) 9-10 Why is the actual multiplier for the U.S. economy less than the multiplier in this chapter’s simple examples? The actual multiplier (estimated to be about 2) is smaller because it includes other leakages from the spending and income cycle besides just saving. Imports and taxes reduce the flow of money back into spending on domestically produced output, reducing the multiplier effect. 9-11 Advanced analysis: Linear equations (see appendix to Chapter 1) for the consumption and saving schedules take the general form C = a + bY and S = - a + (1- b)Y, where C, S, and Y are consumption, saving, and national income, respectively. The constant a represents the vertical intercept, and b represents the slope of the consumption schedule. a. Use the following data to substitute specific numerical values into the consumption and saving equations. National Income (Y) Consumption (C) $ 0 100 200 300 400 $ 80 140 200 260 320 b. What is the economic meaning of b? Of (1 - b)? c. Suppose the amount of saving that occurs at each level of national income falls by $20, but that the values for b and (1 - b) remain unchanged. Restate the saving and consumption equations for the new numerical values and cite a factor that might have caused the change. (a) C = $80 + 0.6Y S = -$80 + 0.4Y (b) Since b is the slope of the consumption function, it is the value of the MPC. (In this case the slope is 6/10, which means for every $10 increase in income (movement to the right on the horizontal axis of the graph), consumption will increase by $6 (movement upwards on the vertical axis of the graph). (1 - b) would be 1 - .6 = .4, which is the MPS. Since (1 - b) is the slope of the saving function, it is the value of the MPS. With the slope of the MPC being 6/10, the MPS will be 4/10. This means for every $10 increase in income (movement to the right on the horizontal axis of the graph), saving will increase by $4 (movement upward on the vertical axis of the graph). (c) C 100 0.6Y S $100 0.4Y A factor that might have caused the decrease in saving—the increased consumption—is the belief that inflation will accelerate. Consumers wish to stock up before prices increase. Other factors might include a sudden increase in wealth or decrease in indebtedness, or a decrease in personal taxes. 9-12 Advanced analysis: Suppose that the linear equation for consumption in a hypothetical economy is C = $40 + .8Y. Also suppose that income (Y) is $400. Determine (a) the marginal propensity to consume, (b) the marginal propensity to save, (c) the level of consumption, (d) the average propensity to consume, (e) the level of saving, and (f) the average propensity to save. (a) MPC is .8 147 Basic Macroeconomic Relationships (b) MPS is 1 .8 .2 (c) C $40 .8$400 $40 $320 $360 (d) APC $360 / $400 .9 (e) S Y C $400 $360 $40 (f) APS $40 / $400 .1 or 1 APC 9-13 (Last Word) What is the central economic idea humorously illustrated in Art Buchwald’s piece, “Squaring the Economic Circle”? How does the central idea relate to recessions, on the one hand, and vigorous expansions, on the other? The central idea illustrated is the multiplier effect that exists in a market economic system. One independently determined change in spending has an effect on another’s income, which then sets in motion a chain of events whereby spending changes directly with the income changes. A decline in spending begins a chain of declines, or, in other words, the initial decrease in spending is multiplied in terms of the final effect of this single decision. This occurs because of the observation that any change in income causes a change in spending that is directly proportional to it. The multiplier effect helps us understand why there is a business cycle as opposed to a stable level of output growth from year to year. In the Buchwald piece, a “downturn” for one person became a downturn for everyone in that fictional economy. Likewise, if the story had begun with a burst of optimism and an increase in spending, it might have rippled through to expand everyone’s fortunes. The multiplier intensifies the effect of a spending change, whether it is an increase or decrease. 148