A Most Fateful Encounter Final

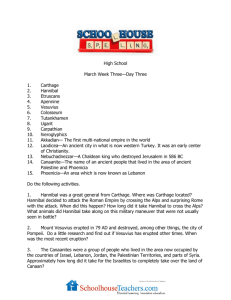

advertisement